Fmr U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt “purchasing” Panama from Colombia

I want to approach the ongoing legacy of former President James Earl Carter Jr. by re-examining his administration’s foreign policies and his style of diplomacy, which differed from both his predecessor and successor. During the late 1970s, Panama, Iran, and Cold War era Soviet Union were all involved in negotiations with him and all of his policies were declared to be utter failures.

Now, however, with the recent release of his private memos, minutes from meetings, and new thoughts on these materials, I will re-examine the main events of his administration with the added benefit of knowing some of the people and decisions made behind the scenes.

By taking a closer look at the Carter administration’s policies, perhaps there are solutions that can be adapted for today’s issues with each country .

Bienvenido a la Zona de Canal (Panama Canal)

Just 40 miles long shore to shore, the Panama Canal connects the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. The Canal Zone was a literal slice of the United States in Panama. Formed after the Hay and Banau-Varilla Treaty (1903), which was negotiated by Philippe Bunau-Varilla, a French National who did not live in Panama for over 17 years and never returned after the treaty was signed.

This treaty set the management of this area at up to $10 million with annual rental payments set at $250,000. At that time, the Canal Zone was completely managed by the United States, which formed a separate enclave within the country. American workers and their families lived and worked within the Zone as Zonians, and this created two wholly different societies within one nation.

Over time, the sight of the U.S. flag waving overhead angered Panamanian nationals. The standards of living within this Zone contrasted greatly to the deteriorating areas outside the Zone, namely its neighborhoods, Casco Viejo and the City of Colon. Eventually, tensions between Zonians and nationals led to a full-scale riot that forced the evacuation of the U.S. Embassy.

The January 9, 1964, flag-related riots are now referred to as Martyr’s Day.

Discussions were re-established between the two governments, but these renegotiations failed to replace the 1903 treaty throughout the latter part of the decade as anti-U.S. tensions escalated throughout Central America.

To gain a clearer picture about this period with the Omar Torrijos–Carter treaties (September 7, 1977) that abolished the Canal Zone (1979) and lead to the canal being relinquished to the Panamanian government (December 31, 1999), I reached out to John R. Nemmers, interim associate chair and curator of the Panama Canal Museum Collection, and Elizabeth H. Bemis (Betsy), associate curator, both from the University of Florida where the collection is currently held.

Fmr U.S. President Jimmy Carter & Fmr Military Leader of Panama Omar Torrijos

Failed Negotiations

Thibert: Why didn’t the negotiations after the 1964 flag riots lead to a new treaty?

John: I can say that it’s difficult to look at any one period as why some treaty happened or did not happen. The reality is that, throughout the existence of the Canal Zone in Panama, there were treaties and negotiations and problems between Panama and the U.S.. There was a treaty negotiation as early as 1959. Is that right, Betsy?

Betsy: 1955 (Remon–Eisenhower Treaty).

John: You’re right. The Panamanians and the Americans had just gone through that process under Eisenhower and there were protests and disturbances at that time. My understanding is there was a feeling that it was too soon after those negotiations to start saying let’s have another negotiation. There was also a growing feeling about knowing how long the U.S. planned to keep the Canal.

A U.S. general stationed at Panama came out and said, “Defensively, the Canal doesn’t mean anything to the U.S. anymore.” We had a two-ocean Navy after World War II. The idea that the Canal was a defensive measure is not true.

So, starting in the 1960s, you had people coming up saying we needed to have serious discussions about the longevity of U.S. interest in the Canal.

What I would say is I think there was a feeling in the short term that they were not going to have another round of negotiations just nine years after the previous negotiations. Longer term, there were already people in government saying, “This needs to be a bigger discussion.” This can’t just be yet another Band- Aid on a problem that has existed since 1903. They were looking at the big picture. Did I miss anything here, Betsy?

Betsy: No, I thought that was good. I also feel the discussions started in a not-so-public way. Much like John is saying, is the political discussion about the cost-benefit analysis of what this was doing politically to our reputation worth what we were getting out of it? So, I do think that there were some soft discussions and lots of things happening way before 1979. The U.S. had been talking about giving the Canal up completely for some time.

Panama had such a strong negotiating position after World War II because we needed something from them. I think that need shifted the tides a little bit.

Thibert: Can you provide an idea of what public sentiment was like in Panama during this time?

John: There were a lot of economic issues from the very beginning of the Canal. It was a U.S. operation in Panama and, in every way, preference was given to U.S. citizens and interests. The U.S. threw its weight around in every way it could. Panama always got the short end of the stick.

Labor is a good example. The U.S. was hiring non- U.S. citizens to work in the Canal, but they were not necessarily Panamanian. They were coming from other countries in Central and South America and the West Indies.

There was a difference in quality of goods, cost, and education. Employees of the Canal Zone could buy things in the Zone from the U.S. cheaper than products in town so there was unfair competition. Wages were different for U.S. citizens. I am probably forgetting a lot of examples but so almost from the beginning Panamanians felt that there was a huge operation that made millions and millions of dollars. Panama was getting the very short end of that stick. If you were a Panamanian you felt discrimination and practices that reinforced the idea that the U.S. was first and Panamanians were second.

Secret Memorandum: Dated June 7th, 1977 from Secretary of State Cyrus Vance

You may have noted press reports concerning demonstrations in Panama on June 6. Demonstrators took down an American flag that was flying jointly with a Panamanian flag near the Canal Zone-Panama border. Demonstrations protested Panama’s high cost of living and commemorated the 1966 shooting of a Panamanian student.

Thibert: Panamanians were not hired at all?

John: They would hire Panamanians, but they were a very small portion of the workforce.

Betsy: In the third locks project, which started in 1939–1940, in the promotional material for that project, the U.S. had to negotiate with Panama. We (United States) promised Panama that we would reduce the labor force that had been brought in. Priority was given to Americans or Panamanians. The project was short-lived because of the war. What happened in 1955 was that we were forced or obliged to start an apprenticeship program for training to work in roles in the Canal but did not include American citizens.

The U.S. and Panama got into a negotiation war about the people of Caribbean descent who came in who were not Panamanian citizens. They were in no man’s land. The majority of non-U.S. citizens who worked and were employed by the Canal, at a later point became Panamanian citizens. They were officially hiring Panamanian in this way.

John: Let’s set aside military matters for now. The workforce for the Canal consisted of a very small number of White American citizens and a huge number of people of West Indian descent from Barbados, Jamaica, and Martinique. As weird as it sounds, Panamanians saw themselves as third-class people compared to White Americans and Black Caribbeans.

Certainly, from the U.S. perspective, anyone other the White Americans was a lower class. I think the U.S. saw [the Canal] as an American operation and the Panamanians got squeezed out.

Betsy: The U.S. said they would send the workforce away when the Canal construction was done. Everyone was supposed to leave, but those people stayed. They had families and their community grew. Panamanians felt like they were taking jobs that should have belonged to people who were born in, or native to, Panama.

That just perpetuated matters. If you lived in the Canal Zone because your dad worked there, then you went to those schools, got a job, and spoke English, and it just became a more insulated community and more and more of those people coming in were just born into the system.

John: I would add to that when we talk to Panamanians of West Indian descent, they also are disgruntled. It is not like the West Indians had it good and the Panamanians did not. It was everyone had it bad. It just happened to be that Panamanians had it worse.

Betsy: A lot of problems were about the living conditions. Even in the West Indian community, the people who grew up in the Canal Zone differed from the people who didn’t. There was tension in that group because it was divided into the haves and the have-nots. Even though they [West Indians] were not making the equivalent of a U.S. citizen, they were making more than what they would get paid if they got a job in Panama. They were living in better housing most of the time and had access to food and education.

Thibert: I have to imagine that this led to a Black Market that got better items from the Canal Zone. Some people may have taken advantage of this.

Did this happen?

Betsy: It did. They called it contraband. For example, your immediate family lived in the Canal Zone, but your extended family lived in Panama. They bought and took things into Panama to give to their extended families.

If you were caught, you paid a huge penalty. It was not that the U.S. did not want you to buy it, Panama was angry because it meant that the person was not buying something in Panama. The country was not getting any tax. No income off of it. The government of Panama did not benefit. For example, you go to the commissary, you buy a turkey to bring to your family. That is one family who did not buy a turkey from Panama.

So the Panamanian government set a strict policy that the U.S. enforced. The U.S. cared that you came into the commissary, but it did not care where you and what you bought after that. The Panamanian government really cared.

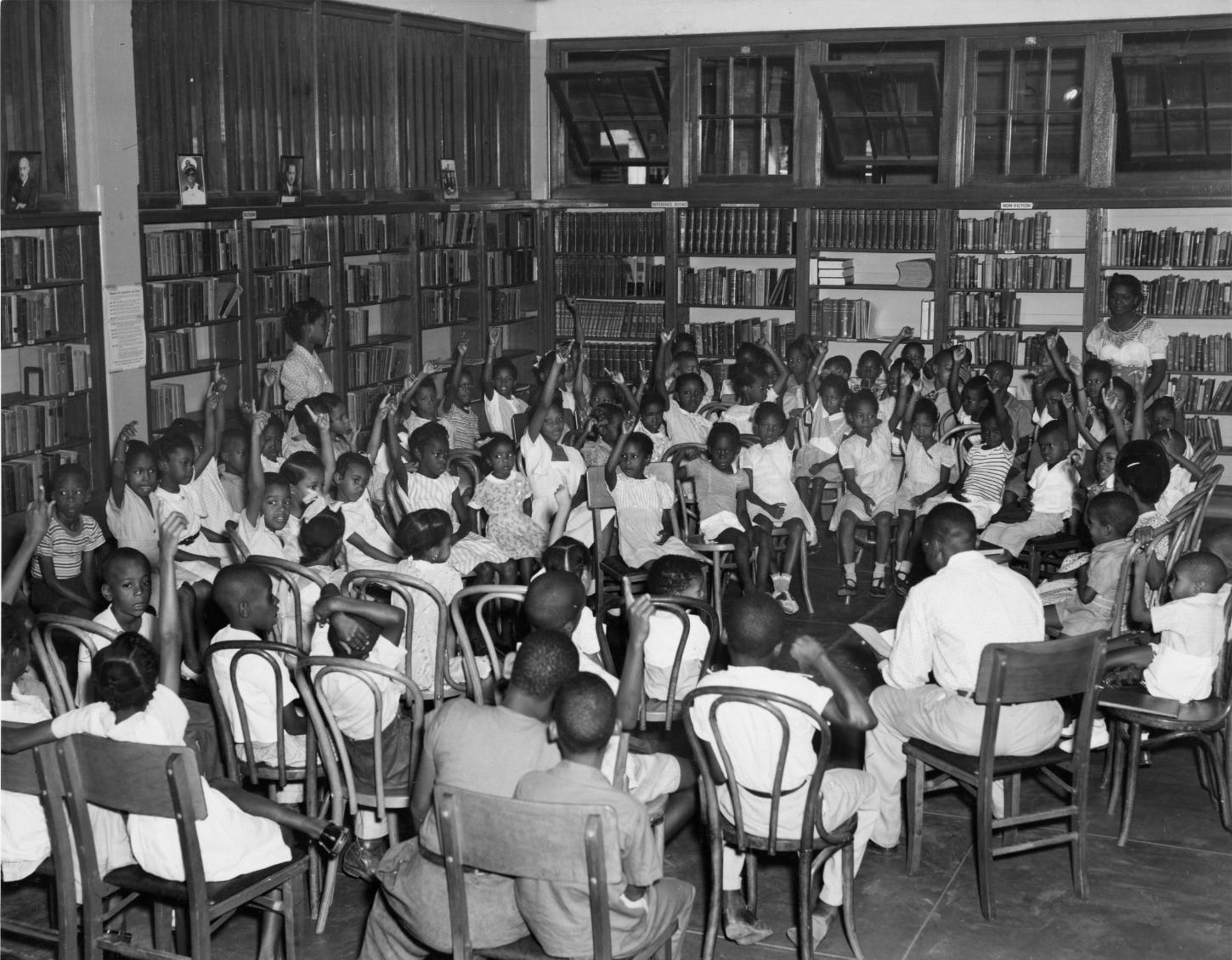

Saturday Morning Story Hour - Panama Canal Library - February 4th, 1950

Be a Good Neighbor

Thibert: Did the United States try to make any conciliatory acts or gestures to smooth things over?

Betsy: There were the Good Neighbor Policies (1933–1945). There was also a lot of stuff during JFK’s presidency (1961–1963). Depends on which decade you’re talking about.

Thibert: What about in the late 1960s into the 1970s.

Betsy: They did it through the military.

John: There were a lot of outreaches through the military. Aid was offered. It is fair to say, I think the military was the main way of doing that through the entire history of the Canal.

Colón (second biggest city) had fires regularly. In the early half of the century, each time a fire broke out, the U.S. military came in.

Betsy: Operation Friendship (May 1958–1961), but JFK did a couple of things.

Thibert: Is this around the time that the military improved the standards of Casco Viejo?

John: The military did the same with Colón. They painted and improved the plumbing and standards.

Betsy: The same with Fort San Lorenzo. Unsure if improvements were a legal necessity as part of the original treaty or done to smooth things over.

Casco Viejo, Panama City

Business as Usual

Thibert: Leading into the end of Richard Nixon’s term and the start of Gerald Ford’s term with Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, what was the policy toward Panama under Dictator Omar Torrijos?

John: My understanding of this period is that it was business as usual. After the flag riots, I think discussions continued about how to improve relations. On the U.S. side, there were probably a lot of people thinking, What’s the long-term plan for the canal?

Starting around 1975, you start to get more news articles and open discussions about the future of the Canal. It was being discussed to the point that it was in the press.

Betsy: My impression was that under the Ford administration is when the discussions begin in earnest. These were more serious discussions about the complete transfer [of the Canal].

John: By 1976, you started having U.S. citizens who worked in the Canal Zone for the government or military getting worried. They begin to organize and send letters to senators and representatives. Committees were formed to talk about the issue. Certainly by 1976, you started to have this real strong, organized effort on the part of the Zonians to try and change the direction the negotiations were going.

I would also say that by 1976, it was too late. The decision had been made. They were protesting past the point they should have.

Thibert: This makes complete sense. There was a memorandum about this from Secretary of State Cyrus Vance to President Carter dated January 27, 1977. This date falls within the first week of Carter’s presidency.

Top Secret Memo dated January 27, 1977 from Cyrus Vance:

1. Panama Canal Negotiations: I am encouraged by the progress that we are making in preparing for the Panama Canal negotiation. At the PRC meeting this morning, we agreed to recommend to you that:

a. The Tack–Kissinger principles should be reaffirmed as the basis for further negotiations;

b. We should commence negotiations within the first two weeks of February;

c. We should accept the year 2000 as the termination date of the treaty, and

d. We should not attempt to hammer out our final position before starting negotiations, but should have our negotiators explore on a what-if basis what the Panamanians would be prepared to give on the remaining issues if we agreed to the year 2000.

Thibert: What was Torrijos’s stance toward the Panama Canal Zone? Did Torrijos have any inkling that things under President Carter would be different?

John: Torrijos was very adamant that he was going to change things. Being a dictator, that was his stance.

Top Secret Memo dated May 12, 1977 from former National Security Advisor of the United States Zbigniew Brzezinski:

The (Panamanian) government has avoided arbitrary imprisonment and unfair trails for political purposes. While far from a model open society or a traditional liberal democracy, Panama has provided basic guarantees of individual rights and has allowed limited freedom of speech and the press.

Betsy: John, what do you think of the notion that it was a done deal? That this was going to happen? It was just a matter of negotiating the terms of it, how much money. To put this in perspective, what can Panama extract from the United States to benefit Panama?

John: I believe that you are correct. I believe it plays out also when you look at the opposition materials that we have in the collection. A lot of early animosity was against Kissinger. If they are going to vilify anyone it is Carter who is Number One. He gave away the Canal.

When you look at their early letters, the writings. It is Kissinger. The negotiations are happening under Nixon. All of that stuff is being worked out. So your right Betsy. By the time Carter is in office it is a matter of what can we get both sides to agree to make this happen. That is how I think this plays out.

Thibert: What was the response of the Panamanian Nationals when the treaty was signed?

John: A lot of Nationals were in favor of it. They had a vote as far as you can trust a vote during a dictatorship. Voting was very strong in support of the treaty. I am a little shaky on what the average Panamanian would have thought. I can tell you what I’ve seen in media.

Betsy: There are some complexities you get at the individual level, if you listen to the oral histories. In a recent interview we conducted, someone was asked how he voted. He was a high-ranking person of West Indian descent. Living in the Canal Zone, he is officially a Panamanian citizen. He struggled with whether it was a good idea for the U.S. to leave. Would the Canal function better under Panamanians? Was it important for the U.S. to be there?

So, I think someone whose level of involvement with the functioning of the Canal might be different than the perspective of someone living and struggling in Panama City. There is a massive wealth differential. People in the daily grind were weary of wondering about Panama’s ability to run the Canal effectively.

John: I would also say, the average Panamanians were very upset. The Canal Zone split their country in half. To get from one side to the other meant having to cross a U.S. border. For Panamanians, that was difficult. If you talked to the average White American Zonians who lived and worked in the Canal, they talked about how easy it was. How fluid the border was. They can easily go into Panama City and enjoy life with no problems. Well, that was because they are White American citizens. If you are a Panamanian trying cross, it was not easy with police and border checks. There is a lot of animosity for the average person who asks, “Why can’t I get from one part of my country to another?”

Thibert: Was a visa needed to go through the Canal Zone and was a check of identification an added hassle?

Betsy: I don’t even know if you were allowed in. There weren’t always checkpoints. It was a matter of being stopped. You would be asked why you were there and then told to leave. There was a little bit of fear when going in as people didn’t just do it. That was early on in the 20th century. Obviously, as time went on, there were more barriers, more of a presence.

In 1959, they build a bridge. There were ferries, but because of the problem of not being able to cross the country, they negotiate for a bridge called The Bridge of the Americas built by the U.S. Panamanians could drive across the Canal Zone. There were constant negotiations about how much money Panama was getting. We now start to baby step across the latter half of the 20th century.

The U.S. government started to make “concessions,” which were the different things that the U.S. was going to do to help Panama. At some point, it was not worth it to the U.S.—didn’t need the Canal Zone for defense and not making enough to justify its presence there.

To add to what John said earlier, on the individual level, the end of the Canal Zone was probably what people really wanted. The Panamanians had big problems with the Zone: It’s ruled by different laws, its people have a different lifestyle, and it is in the middle of the country.

I have heard people say who should run the Canal. The U.S. should not have simply ended the Canal Zone. Instead, the U.S. should have kept it running to solve a lot of people’s problems.

Thibert: What were the U.S. Nationals and the Republican Party’s response to the treaty?

John: It was mostly a campaign issue. Reagan as a conservative said that Carter and the Liberals were giving away the bridge. This was a blow to the U.S. and a blow to the economy. The Canal negotiation and its aftermath was now playing out on a national level. So much so that it is a campaign topic for Reagan.

Top Secret Memo: April 4, 1978 from Zbigniew Brzezinski:

A plurality of the American people now favors the second Panama Canal treaty by 44% to 39%, according to the results of a Harris poll announced yesterday. The poll indicated that the addition to the first treaty of the two amendments dealing with emergency rights for U.S. forces and warships tipped the public in favor of the second treaty. Without these provisions, Americans overwhelmingly reject giving control of the Canal to Panama.

Betsy: It was all-consuming to the Zonians: the end of their life there, the end of their livelihood, the end of the place that was their home for generations. To Americans back home, I am unsure of how much they cared. Once it became strategic because it turns into “oh, we are going to make Carter look bad,” it became a tool.

John: I am going to assume that if you asked the average person in 1976, “hey, the U.S. is going to give back the Canal,” I am not sure that the average person would have an informed opinion. I think it was a matter of distance. If you asked in the 1930s, people would think of it as vital to our defense. At that time, we didn’t have a two-ocean navy. In 1975–1976, most people were not thinking of the Canal.

Keep The Panama Canal Rally - 1977

The Last Twenty Years

Thibert: Tell me about the last days of the Canal Zone? Can you give me an idea of what it was like for those families to come to the United States?

John: There were a lot of turnover details, such as lowering the flag ceremonies at bases, schools, and fire stations. Everything was negotiated to each detail of when everything would be turned over. You have this very structured turnover of everything. One day an item is American and, after the determined date, it is Panamanian.

People knew when the turnovers were. Everything was being publicized and discussed. People were relocating during the first exodus around October 1, 1979. This was a huge time full of turmoil that many Zonians have not gotten over to this day. The other thing happening was a 20-year gearing up for the transition in 1999.

Besty: They could see the end of the Canal Zone coming. They had things charted out and how it was going to be turned over. People were very attached to this space that now had a 20-year end. People wanted to constantly mark and honor the end of something.

I did an interesting interview with someone who was an administrator. He talked about there being an issue with payments to Panama. People couldn’t spend money leading into the end. Suddenly, they could not have a Canal Zone license plate on their car. They had to have a Panamanian one because the Canal Zone didn’t exist.

Top Secret Memo dated March 22, 1977 from Zbigniew Brzezinski:

Torrijos demanded the U.S. be considerably more forthcoming regarding the lands and facilities that would be passed to Panama under the treaty. He emphasized Panama’s requirement for port areas on both the Atlantic and the Pacific. Torrijos said he was under pressure to show movement in the talks, and urged, if the settlement was going to be prolonged, that the U.S. make a gesture by transferring significant real estate to Panama.

Thibert: So, for White Americans, I assume they came to the United States. For the people who earned their citizenship, were they stuck in a bureaucratic limbo?

Betsy: Many White Americans stayed throughout the transfer. Certainly, a lot of people left or planned their retirement, but there were those who decided to stay after the turnover. The U.S. negotiated a favorable retirement program for U.S. citizens.

John: The treaty spells out the 20-year transition period. They couldn’t simply leave behind the keys to the house as of 1979. They needed to be trained. They were frozen out. There weren’t any Panamanians in any positions at the Canal. The transition was bringing them up to speed to manage.

Because of how it was managed, it is not surprising that, like Betsy said, they were still dealing with issues. I imagine it was a huge undertaking: transfers of property, how to pay people, and other issues.

Betsy: The Canal Zone police did not exist anymore. One day, they were here, the next day, gone. I spoke to a very high-ranking person in motor transportation. He was once the highest ranked in his position, the next day, a chauffeur.

Thibert: How did this effect people mentally?

Betsy: People were very traumatized. You talk to them stepping away from the political space and discussing what should have or could have happened. This was their everyday life for a century. They struggled. They faced the end of something they loved. They all spoke fondly of Panama. Then the trauma of friends coming and going. Lost jobs. Being transferred and shuffled around. My sense, after speaking to them, is that this was extremely difficult…

John: …to the point that some former Zonians will lean in and say, “yes, we had a colony there and we shouldn’t have been there.” They will admit that to you, but in the next breath, they mention how traumatic it was and how they hate Carter for giving away the Canal.

Betsy: You know the day it will end. The day my entire existence will change.

Thibert: Were there people who had lived there entire life within the Zone?

Betsy: Yes, many of them.

John: There were people who lived there for three generations. It would be surprising if anyone made it to a fourth generation. There were many people who worked for the Canal and had children who worked for the Canal. They didn’t know the mainland U.S. For them, it was a vacation destination. The United States was not their home.

Thibert: Did the Panamanian Nationals see both sides of this? These people had lived there all their lives, so perhaps should we take it easy on them?

John: It was mainly that the U.S. equals bad. They shouldn’t be splitting our country in half and treating us in this way.

Betsy: We actually got asked that question about taking it easy on them. They didn’t know. They were surprised how much these people actually loved the country. The larger political narrative was so strong that individual opinions and experiences were swept away.

The treaty goes on and the experience between the U.S. and Panama gets very tense, especially during the Noriega years (military dictator 1983–1989). There were not as many interactions during this time, and they were certainly not as comfortable as the interactions they once had.

Thibert: Fast forward to the turnover of the Canal in 1999, what was it like? Tell me about the celebrations.

John: There was a big celebration for the end of the transition period for the Canal. Now it belongs to Panama. From the Panamanians’ perspective, it is what they have worked toward for decades. It’s realized, and 1999 is seen in a very positive light.

Thibert: For Zonians, how did they look at it?

John: It was a depressing year and the official end of U.S. control. My impression is, and I have never asked anyone this, but I believe 1979 was much more dramatic than 1999. I do think that, after talking to people, by 1999 there is greater confidence on the American side that Panamanians can manage the Canal. I think the average American did not care much for the Canal. There were very pessimistic opinions in 1979. Then 1999 was different because there was more confidence.

Betsy: There was an issue about possibly a protest on the Bridge during the transfer ceremony. Carter was there with the Panamanian President Mireya Musocco. I believe it was in an interview that someone spoke about it and the tremendous amount of hostility during the ceremony from an American perspective.

Then a couple of people who were in high school during that time spoke of how depressing it was because the drawdown was so severe that the population began living in this place that was dramatically different. There weren’t as many people living there. It was just very different.

A former teacher spoke about going to school there. Her family had been there since construction (1903). She had never left. She taught there. She just sat on the floor and cried on the last day when they were packing up.

I agree with John that 1979 was a massive trauma that it was over. For those who stayed, it was a slow death of what they love. Many people still cry when talking about it.

Fmr Pres. Carter turning over the Canal to Presidente Mireya Rodríguez 12.31.1999

Conclusion

Upon hearing more about the sentiment toward the Canal, especially during the years after World War II, it becomes apparent that the acclaim later given to Carter may not be entirely earned. The United States had been looking for an exit for some time. Whether it was under President Ford or Carter, the last days of the Canal Zone were marked.

The only difference is that, if the turnover happened under Ford, it would not have been used so decisively as a political ploy. For Reagan, it was absolutely used in this fashion.

Another item that strikes me as interesting is the relationship between President Carter and Military Leader Torrijos. For those not familiar with Former Commander of the Panamanian National Guard Omar Torrijos, he was the former dictator of Panama from 1968 to 1978 who took leadership of the country after a coup that overthrew President Arnulfo Arias (1968).

Since we are focusing on Carter’s foreign policy and it’s effects on people on the ground, I am going to focus on the negotiations. For that, I refer to a book that Carter often used as inspiration for his negotiations titled, Getting to Yes. Negotiating Agreement Without Giving In (Fisher, Roger et a 1981). There is a section that refers to “Focus on Interests Not Positions” that I believe could have been an inspiration.

“Interests define the problem. The basic problem in a negotiation lies not in conflicting positions, but in the conflict between each side’s needs, desires, concerns, and fears. Interests motivate people; they are the silent movers behind the hubbub of positions. Your position is something you have decided upon. Your interests are what caused you to so decide.”

This is advice he may have taken to heart, especially in relations with Iran.

Governor Jimmy Carter on What’s My Line - December 13th 1973

Very interesting real-life perspectives.. being torn between the comforts that colonization provides and knowing / understanding the disparity and bigotry.

Great piece of in-depth journalism. It’s impressive how people become attached to the places were they were born and where they work, and how nationalistic interests can be antagonistic to those attachments. This situation was used by Hitler to invade the Sudetenland is what was then Czechoslovakia.