U.S. Foreign Policy: Iran (1977 - 1981) (History)

Did Former President Jimmy Carter Owe The People of Iran An Apology?

Former United States President Jimmy Carter with Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, Shah Of Iran, November 1977

Help me reach 1,000 subscribers by December 31st, 2025. Please share Emancipatory Research with anyone who enjoys reading, learning and conversing about history and geopolitics.

Is former President Jimmy Carter responsible for the current state of Iran? Many individuals have answered with an unequivocal “yes.” Social media posts of the former Shah (Reza Pahlavi) often suggested, in the comments, that he was let down and then failed by Carter and that his reinstatement and backing by the U.S. government could have prevented the Iranian Revolution in 1979. Further claims point to documents obtained by the BBC in 2016 that highlight how the “Carter administration paved the way for Khomeini’s return to Iran from exile.”[1]

What I aim to do here is disprove that the blame falls on the shoulders of former President Carter (1977–1981). I want to highlight that the Carter administration was put in a no-win situation. Unfortunately, by the time Carter was sworn into office (January 20, 1977), the writing had long been on the wall. The signs were simply ignored. The Shah was too arrogant and Carter was too unproven to know or understand how to navigate the situation.

Iran could have prevented it’s “second revolution,” but that opportunity was lost under former President Richard Nixon (1969–1974).

Various newsreels leading up to and during the Iranian Revolution 1977 - 1979, Source ABC News

The Blame Game

In a 2023 article by Lisa Daftari, titled, “Why Jimmy Carter Owes the Iranian People an Apology,” the statement is made, “Carter’s true transgression—the original sin that has complicated and shaped U.S. policy in the Middle East ever since—preceded that [Operation Eagle Claw]. Carter’s gravest mistake was his disastrous undermining and lack of support for the legitimate ruler of Iran, Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, who was waging a valiant battle against leukemia as the revolution unfolded in his country.”

To understand how flawed this statement is, let me point out a number of inaccuracies. The United States’ policy toward Iran was shaped by decisions made both concurrently and intermittently not only by the United States but also by the United Kingdom, and then by the Soviet Union during major events including:

• Removal of former Reza Shah Pahlavi in 1941 by the Allies due to possible ties to Nazi Germany.

• Splitting the country into two spheres: the United Kingdom in the South for oil, and the Soviet Union in the North for strategic importance.

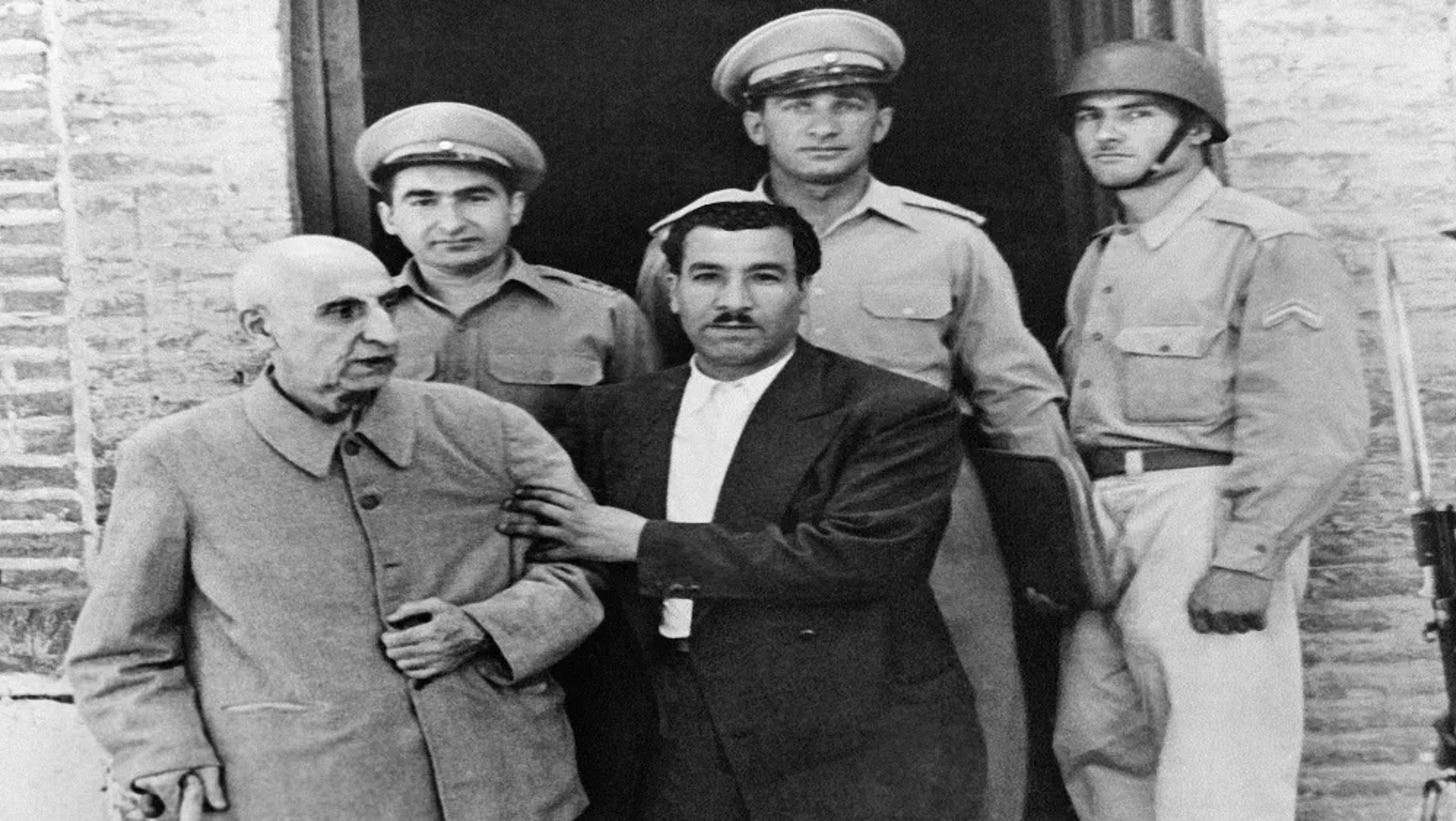

• Removal of Mohamed Mosaddeq (1953) through a coup orchestrated by members of the CIA’s Middle East desk under Kermit “Kim” Roosevelt Jr. and members of Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi’s (son) inner circle.

These three underlining events continue to be the go-to course of action for world powers to destabilize, influence, and control countries. The plan, despite failing on many counts, is still used all together or as separate parts.

“The Shah arrived home in triumph on August 22, at the same time that Mosaddeq was apprehended and sentenced to house arrest, and (Fazlollah) Zahedi was granted $5 million by the CIA so that he could meet month-end payrolls (regular subsidies would follow later). At a secret midnight meeting the following day, the Shah raised a glass in toast to Kim [Kermit Roosevelt] with the words, ‘I owe my throne to God, my people, my army—and to you!’”[2]

The second error is the assumption that supporting the Shah was an option when general sentiment toward Pahlavi was “Death to the Shah” and “Hang the American puppet.”[3] Equal disgust was vocalized toward the United States as anti-Western sentiment was amplified during the Ayatollah’s rise. Finally, the Shah installed Prime Minister Shapour Bakhtiar to rule in his absence, but with a destabilized government leading to the military switching over to Khomeini or quitting, if Carter had supported the Shah, it would have meant supporting Shapour who by this time had no real political power.

Later in the Daftari article, a reference is made to a 2016 article by Kambiz Fattahi, “Two Weeks in January: America’s Secret Engagement with Khomeini,”[4] that quotes Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini’s January 27, 1979 secret message to Washington in which he requests, “‘If President Carter could use his influence on the military to clear the way for his takeover,’ Khomeini suggested, he would calm the nation. Stability could be restored, America’s interests and citizens in Iran would be protected.”

A little context is needed. The book by Malcolm Byrne and Kian Byrne, titled Worlds Apart: A Documentary History of U.S.–Iranian Relations, 1978–2018[5] is a collection of declassified documents relating to U.S. foreign policy toward Iran. An assessment is made by the authors of Khomeini reaching out to the Carter Administration.

“Khomeini ’s first major point is to call for Prime Minister Bakhtiar’s ouster. He intends to establish his own government and there is no room for the Shah’s appointees. Khomeini declares that he has no ‘particular animosity with the Americans’ and that the new Islamic Republic is ‘nothing but a humanitarian one.’ This contrasts sharply with the anti-American rhetoric Khomeini is already known for (for example, calling Carter ‘the vilest man on earth’).”[5]

At this point, the Carter administration is unfamiliar with Khomeini but is all too familiar with his insults. There was no previous contact made prior to January 27. The only certain fact is that Khomeini is popular and that the Iranian government is firmly in his hands.

Carter chose inaction and the immediate evacuation of American citizens from Tehran. To understand his decision requires an understanding of the events leading up to 1979.

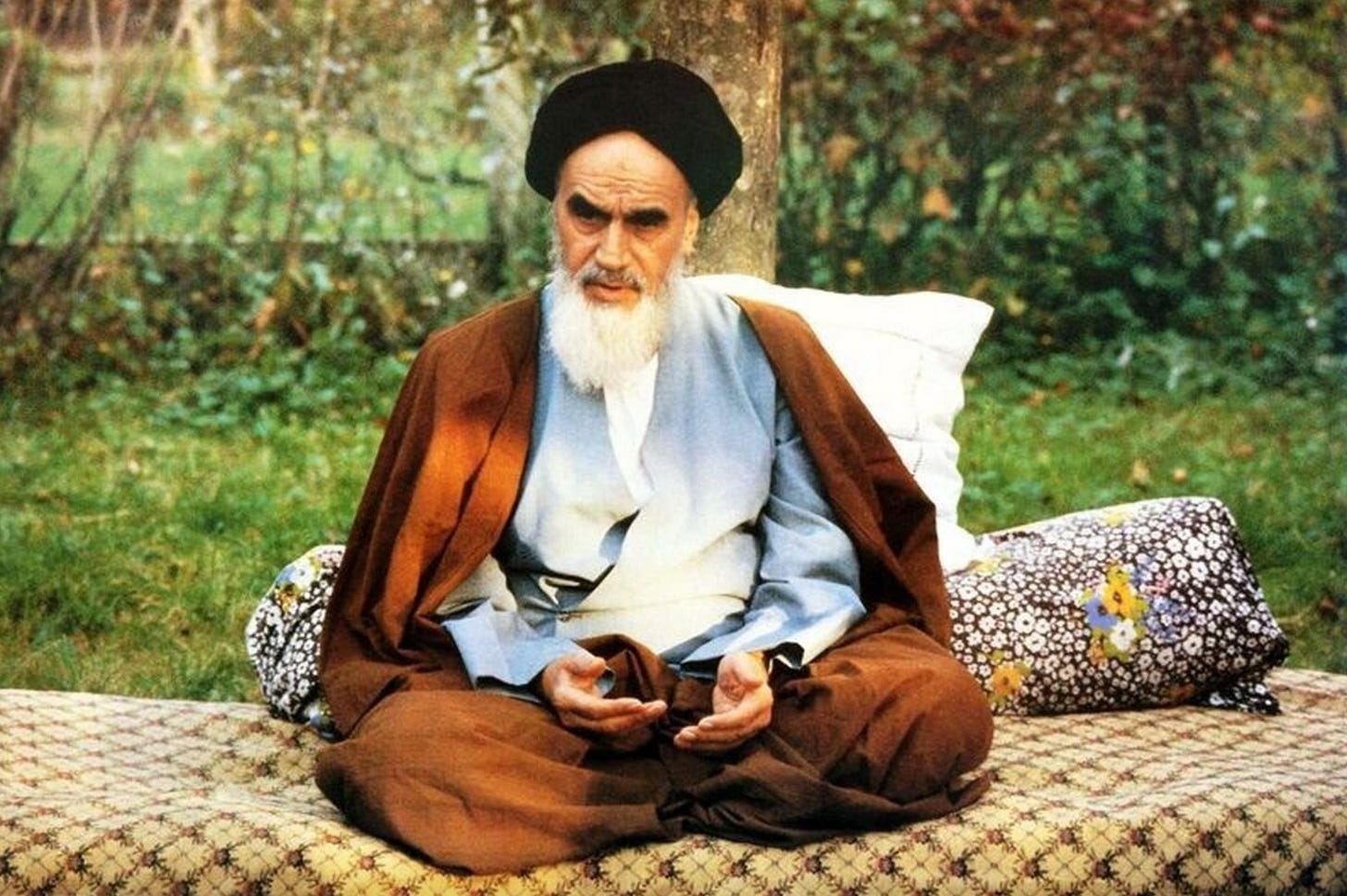

Ayatollah Khomeini, Source Unknown

Long Live the Nation of Iran

The foreign influence that began during World War II serves as an ideal point to scrutinize the altered trajectory of Iran (Persia). The event falls in mid-century (1946), giving us just over 30 years before we reach the events of the Revolution of 1979. There is almost an equal amount of time prior to the war that should be reviewed to understand where Iran was heading and could have gone.

An ideal starting point is 1909–1911 with some context needed on the events leading up to modern Iran. Shortly before this moment, Iran had already experienced its first Revolution (June 1905–August 1906), Civil War (June 1908–July 1909), and a Constitutional Crisis (1906–1909). A summarization of the Revolutionary Period is found in the following quote, “Thus Iran in 1905 was rapidly moving toward a political revolution. The traditional middle class having coalesced into a statewide class, was now economically, ideologically, and politically alienated from the ruling Qajar Dynasty. The modern intelligentsia, inspired by constitutionalism, nationalism, and secularism was rejecting the past, questioning the present, and espousing a new vision of the future. Moreover, the traditional middle class and the modern intelligentsia, despite their differences, were directing their attacks at the same target—the central government.”[6]

A bad harvest, cholera, decrease in trade and the continuing Russo-Japanese War (1904–1905) were all transpiring in 1905. The combination led to inflation that consequently brought about protests throughout the country. As the initially peaceful protests continued throughout the year, a poor governmental decision to beat the soles of two sugar merchants due to an accusation that they had been hoarding sugar shifted the frustration of the crowd to anger. The merchants pleaded that the increased price of the staple item was due to the war, but the punishment was still implemented. Public reaction was swift, leading to store closings and mass protests in the main square in Tehran. Protestors sent the government four requests: replace the governor of Tehran, dismiss Naus, enforce the sharia, and establish the House of Justice.

As protests increased, violence was met by mass arrests which were met by bigger crowds and ultimately led to a fifth request: establish a Constituent National Assembly.

The two-year process leading to the nation’s first constitution that included a role for the Parliament, individual rights, and the most contentious issue—the role of government. Using a translated Belgian constitution as a template, Iran created a parliamentary system of government and a constitution titled: The Supplementary Fundamental Laws, which in its two sections gave the nation the following:

First section: The guarantee of equality before the law; protection of life, property, and honor; safeguards from arbitrary arrest; and freedom to publish newspapers and to organize associations.

Second section: Separation of the legislative and executive branches. The legislative branch had the ability to appoint, investigate, and dismiss premiers, ministers, and cabinets; to judge ministers for “delinquencies”; and to approve military expenditures. The executive branch was under the Shah but its work was carried out by “ministers.” The Shah had to take an oath of office, and budgets had to be approved by the National Assembly.

Despite the civil war and the constitutional crisis, by 1909, the nation was moving toward a fairly good start. Unfortunately, a volatile political environment developed that was further weakened by tribal warfare throughout the nation, which became worse when German arms dealers were discovered selling arms to various tribal leaders. Geopolitically, Iran was being attacked by all sides. By 1911, the British and Russian militaries invaded the interior and, by 1915, the Ottomans had invaded.

On February 21, 1919, a coup began when Colonel Reza Khan of the Cossack Division entered Tehran armed by British soldiers stationed in Qazvin with weapons, supplies, and payments for his troops. He promptly arrested a high number of politicians and promised the shah, Ahmad Shah Qajar, that these actions were necessary to prevent another revolution.

By 1921, Reza Khan had consolidated his military power as he forged agreements with the Soviet Union. He replaced the British and Swedish soldiers who maneuvered into positions within the War Ministry with members of the Cossack Division. He then ended rebellions and radical movements throughout the country and consolidated his position in both the military and government with the strength and support of the populace.

“If Reza Khan based his power predominately on the military, his rise to the throne would not have been so peaceful and constitutional without significant support from the civilian population. Without such civilian support, he might have been able to carry out another military coup d’état, but not a lawful change of dynasty, he might have seized the capital, but not the whole country with an army of a mere 40k men; and he might have rigged enough elections to provide an obedient party, but not enough elections to provide himself an obedient party, but not enough to enjoy a genuine parliamentary majority.”[6]

Reza Khan’s path to the throne was paved not simply by violence, armed force, terror, and military conspiracies, but also by open alliance with diverse groups inside the Fourth and Fifth National Assemblies.”[6] By 1925, Ahmad Shah Qajar was removed, officially ending the Qajar Dynasty and commencing the Pahlavi Dynasty.

The Last Qajar Kings: (L-R) Naser al-Din Shah Qajar, Mozaffer ad-Din Shah Qajar, Mohammad Ali Shah Qajar, Ahmad Shah Qajar. Source: Unknown

The Pahlavi Autocracy

Reza Shah Pahlavi’s abatement can be attributed to two different events. The first was the return of what was left of the political class who were pushed to the side during his time as Shah. The second was the development of an economic relationship with the Nazi Regime. He was designated as the Shah in 1925, and his fall in 1941 led to his subsequent removal to Mauritius and finally to South Africa where he passed in 1945.

Sitting on a marble throne in the Golestan Palace and wearing royal robes over his military uniform, the new ruler was a welcomed change over the chaos under the Qajar Dynasty and everything that came to be identifiable with it: corrupt politicians, foreign interventions (Russia and England), and the failure of the Constitutional Revolution.

‘Abd al-Hosain Teymurtash, Firus Mirza Nosrat al-Dowleh, ‘Ali Akbar Davar, and Ja’farQoli As’ad Bakhtiyari served as the initial four ministers who helped usher in the many advances made under the new dynasty. They would all pass away under various circumstances due to the Shah’s growing distrust of each them.

“Inspired by the example of Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, whose reforms were molding Turkey into a modern secular nation, Reza Shah soon embarked on his own agenda to refashion a contemporary Iran. His industrial and education reforms were to generate a new cadre, one beholden to the monarchy and sharing its vision of radical change. The army he built marked the first time that Iran moved beyond militias to concentrate on powering the hands of the state. He tried to knit Iran together by constructing a railroad system and developing ports. He even became an unlikely champion of women’s emancipation by prohibiting the veil in public.”[7]

During Pahlavi rule, Iran developed a national identity while under the strain of the Great Depression (1929–1939). Neighborhoods, bazaars, and hallmarks of the Qajar Dynasty were razed for public spaces such as parks and avenues. New buildings, such as the Tehran Central Post Office, Tehran University, National Bank of Iran, Ministry of Justice and Ministry of Finance, were constructed. Consequently, the remaining old buildings and neighborhoods became homes for the impoverished and lower classes. The Constitution (1906–1907) protected Iranians by providing their own version of a Bill of Rights, but a lack of understanding of how these laws were enforced and interpreted kept people mainly influenced by Islamic law.

The remnants of the old politicos were left powerless, and the tribal leaders were made weak. Each group was unable to do anything due to the increasing oppressive autocracy that included secret police. Over time, the initial adoration that the Shah once had changed into fear and distrust that coincided with World War II.

“Before 1933 and the rise of the National Socialist Party to power in Germany, Iran relied on German technical and financial expertise for building new industries, railroad construction, the banking system, and training the workforce at a German-run technical school. German industrial ascendancy from the early 1930s made that country an attractive choice for Iran’s trade and industry and a willing partner. Hoping to be on the side of the winner and reap the potential benefits, in August 1939, at the outset of the war, the Shah appointed as the new premier the French-educated Ahmad Martin-Daftari who was known for his Germanophile tendencies.”[8]

By August 1941, Iran was occupied by the British and Russia, despite its neutral status. After Winston Churchill became prime minister in 1940, the Shah attempted to negotiate with the British government, which availed him nothing. On the other side, the Germans began to view the Shah as a puppet of the British. Regardless of the Allies’ initial promises of respecting Iran’s borders and continued attempts by the Shah to come to an agreement, Iran was caught in the middle.

By the end of Reza Shah’s rule, the British had acquired the southern half of the country for the oil needed for its war machine. The Russians occupied the northern half for its strategic location. Iran was just a tool of the Allies.

Reza Shah Pahlavi, The Founder of The Pahlavi Dynasty and The Father of The Modern Iran, Iran 1920s Source: Unknown

I Knew That They Loved Me

Mohammad Reza Pahlavi’s (son of Reza Khan Pahlavi) decision to install Mohammad Mosaddegh as Prime Minister of Iran in 1951 was a surprising choice, given the temperament of the new Shah and their shared experiences. At age 69, the elder statesman and trained lawyer had been adamantly against the British due to their long-standing influence over their internal politics and oil fields. He was also not a friend to the other imperial powers. He often using the ruse of being an absent-minded old man, which included fainting to get out of taut situations.

Some context is needed to clarify the dynamic between the Iranians and the British. Oil had long been a resource that the British coveted in Iran. Discovered in 1908 by British citizen William Knox D’Arcy, the Anglo-Persian Oil Company (APOC) was formed under a preexisting 1901 agreement that gave exclusive rights to D’Arcy for the next 60 years. By the onset of World War I, the British government had acquired 51% of the company’s shares. This situation created an opening that later allowed for England to take even more land after 1945, effectively creating a colony. With a relationship that had always been onerous, especially due to the APOC not honoring its end of the profit-sharing deal and the abysmal working conditions that lead to strikes and drops in productivity.

By the time Mosaddegh became prime minister, the consequent back and forth between himself and Churchill (now enjoying his second term as prime minister) had increased. The Shah’s game of playing foreign powers against each other was viewed as a dangerous strategy that put the nation at risk. Mosaddegh was much more direct in his handling of the situation that included the nationalization of the oil fields.

Mosaddegh’s decades in various roles in government, self exile (1919), abuse and arrest under Reza Shah (1940), and release (1945) all combined to make him a national hero.

“Mossadegh envisioned an Iran that was independent, free and democratic. He believed no country could be politically independent and free unless it first achieved economic independence. He sought to renegotiate and reach an equitable and fair restitution of rights of Iran with APOC but was faced with intransigence by the company.”[9]

Mossadegh attempts to nationalize the oil fields and end British interference in Iranian affairs would not come to fruition during his term (nationalized in 1954). The strained relations forced the Iranian government to close the British Consulate after a British spy ring was found within the government and in various influential circles prompting a recall of the British ambassador Francis Shepard.

Like father, like son. The Shah was intimidated by Mossadegh. Adored throughout the Middle East, he attempted to court U.S. aid and mediation with the British but was turned away. He then went to The Hague and pleaded his case against the APOC. He was removed from his position by the Shah and replaced by Ahmad Ghavam. Public protests became so large that, to restore order, the Shah’s security forces killed many protesters. This prompted Mossadegh to be reinstated as the prime minister with the added role/title of minister of defense, a role that he had requested but was initially denied. This dual role is allowed in the constitution.

Throughout these events, the United States attempted to keep its distance. Yet its involvement created a relationship between the Shah and the U.S. government that would last until the Shah was removed from power.

Initially impressed by his anti-communist stance and dislike for foreign powers, the U.S. government eventually found him to be emotional, irrational, and overall unsettling. His fainting spells grew tiresome and his demeanor categorized as Orientalism. There was also a concern that Soviet influence might become an issue that the Iranians could not overcome.

In the end, it was the prodding of the British that lead to the CIA’s removal of Mosaddeq under Operation Ajax.

“As yet, no one in Washington was proposing an operation to get rid of Mosaddeq—that idea originated with the British. Somewhat improbably, it was two professors of Persian, Ann “Nancy” Lambton of London University and Oxford Robin Zaehner, who first proposed, in 1951, the anti-Mosaddeq plot that culminated in the 1953 coup. The idea received the enthusiastic blessing of new Prime Minister Winston Churchill—a firm believer in both clandestine warfare and Britain’s right to Iranian oil.”[10]

The culmination of a joint CIA and MI-5 operation came on August 19, 1953, as crowds gathered in Tehran holding pictures of the Shah and shouting for the removal of Mosaddeq. A few hundred people were killed as the military attacked the crowd. In the end, the prime minister was arrested.

A cheerful Shah was receiving updates while in Rome and remarked, “I knew that they loved me,” before returning home to Tehran. Sure to thank his new compatriots for his latest good fortune, he was quoted as saying, “I owe my throne to God, my people, my army to you, and, of course, to that undercover assistant of yours whom I shall not name.” Head of the CIA operations, Kermit “Kim” Roosevelt Jr. later quoted that the Shah toasted him personally.

The removal of Mossadegh was Iran’s first lost opportunity to avoid the revolution of 1979.

Mohammad Mossadegh (bottom left) being removed from office during Operation Ajax, 1953 Source: Unknown

The Shah’s Mistakes

Instead of an overview of Mohammad Reza Pahlavi’s time as Shah (1941–1979), I want to focus on his major mistakes made during this time. Turning back to the initial article stating that the Shah should have been returned to power, I want to highlight that if he had been brought back to Iran, he would not have lived for much longer or been disposed, even if not diagnosed and eventually dying of chronic lymphocytic leukemia on July 27, 1980.

To reinforce my argument, I will cite a number for quotes to highlight that my conclusions were not formed in a vacuum.

The Shah thoroughly weakened, disposed, and murdered (even if by others) any and all political individuals who could have become a rival or threat to his power. This caused young people to avoid politics and go elsewhere.

“Although the National Resistance Movement began with high hopes, within four years it was in complete disarray. A number of factors accounted for the collapse. In 1956, the regime arrested almost all its leaders on the grounds that the organization was undermining the ‘constitutional monarchy.’ Moreover, the leadership was divided, and some—notably Bazargan and Talqani—insisted on denouncing the Shah by name and dismissing the whole regime as illegitimate, whereas others preferred to focus their attacks in specific issues and on particular ministers.”[11]

The Shah feared, ignored, and allowed for the growth of charismatic religious leaders to rival his own. This became a magnet for disillusioned youth. Please note the following comments and observations were made during the Shah’s “White Revolution” which began to modernize Iran and improve the well-being of Persians.

“During Mubarak in 1963, the religious leaders and not the political parties inspired and encouraged the masses. The major lesson to be drawn from 1963 is that the ‘ulama have a crucial role to play in our anti-imperialist struggle—just as they did in the tobacco crisis of 1891–1892, in the constitutional revolution of in 1905–1911 and in the nationalist movement of 1950–1953.”[11]

“The Shi’i leaders have always helped Iran’s struggles against despotism and imperialism. Since the days of the Constitutional Revolution, since the bleak years of Reza Shah’s repression, and since the bloody demonstrations of 1963, the ‘ulama have allied themselves with the masses. Ayatollah Khomeini, who had lived in exile since 1964, is now the main opponent of the regime. The Shah, the so-called religious experts by the regime, and other national traitors do their very best to drive a wedge between us and the progressive religious leaders….We will do all we can to create unity between the political opposition and the religious leaders, especially Ayatollah Khomeini. United, we will destroy the hated regime.”[11]

The Shah replaced his inner circle with sycophants and strawmen. This left no prospective replacements other than puppets who were not able to deal with any conflict unless under the direction of the Shah.

“A corrosive alienation had descended in Iran in the mid-1960s. By this time, the elder statesmen with the confidence and expertise needed for independent action had all but disappeared. Iran no longer produced great men such as Qavam, Mosaddeq, and Amini. In their place were technocrats who were not permitted to make any decisions. No official was indispensable, or even allowed to amass much power. Contradicting the Shah usually meant dismissal or at best a transfer to a less important post.”[12]

“Iran appeared to be a country on the move led by a modernizing monarch. The economy grew, the bureaucracy enlarged, and new industries gave the regime an ample financial cushion. The Shah seemed to have finally tamed Iran. The institutions of the state, such as the Majlis and the cabinets, were shadows of their former selves, incapable of challenging monarchical fiat or mediating between the palace and the public.…Yet beneath the veneer of stable progress there were signs of discontent. The growing middle class had no avenue for channeling its grievances or asserting its claims. Corruption was becoming endemic. A spirit of cynicism and alienation was descending on Iran, particularly in the universities, which became hotbeds of agitation. The Shah had loyalists but few who truly believed in the system. The paradox of Iran was that it was a dynamic country that few wanted to live in.”[12]

Shah speaks on Israel lobby, foreign policy, and the upcoming U.S. elections. 1976 Source: 60 Minutes

Spheres of Influence

At this point, I want to focus on what may be the most interesting aspect of this period: the relationship between the Shah and the United States. What I want to make immediately clear is that the Shah was not a puppet to foreign governments. Contrarily, the Shah was firmly in control of their relationship often “educating” the U.S. on the geopolitics of the region.

“The Shah was accustomed to giving illuminating titles to his foreign policy doctrines. In the 1950s, he conjured up “positive nationalism,” the notion that Iran’s interests lay in holding tight to the American alliance. By the 1960s, positive nationalism had been overwhelmed by the changes in the global order and in the Middle East itself. The Soviet Union did not seem all that menacing, and the United States was not entirely reliable. Arab radicals where tamed by Israeli armor in 1967, and a year later, the British announced its decision to leave the Middle East. The Shah wanted to become the hegemon of the Persian Gulf but sensed he could not do so as America’s client. In the last decade of his rule, he spiked up oil prices, cozied up to the Soviet Union, cemented his ties with American on his terms, and obtained grudging accommodation from the Arab sheikhdoms.[13]

For those who believe the CIA’s Middle East desk under Kermit “Kim” Roosevelt Jr. had a clear grasp of both the situation and Middle Eastern politics, their perspective on this should be realigned. Kim Roosevelt was a cowboy, not in the literal sense but in mentality. The grandson of Rough Rider and former President Theodore Roosevelt (1901–1909), he was raised in an environment filled with foreign adventure and tales of intrigue. Even his nickname “Kim” comes from the title of a Rudyard Kipling book, which was popular at the turn of the 20th century, about a boy finding adventure within Asian lands. From his perspective, the Middle East was an exciting and exotic adventure of new lands. In actuality, he was a voyeur. His retelling of events highlights how he saw himself in this story. The earlier comment made during the Shah’s toast after removing Mosaddeq is an example.

From Kim’s perspective, he heard “ I owe my throne to God, my people, my army –and to you!”. What was actually said was, “I owe my throne to God, my people, my army, to you and, of course, to that undercover assistant of yours whom I shall not name.” In actuality he had very little to do with the joint C.I.A., MI5 affair.

“According to a 2010 book by a former Iranian diplomat, it was not Kim Roosevelt who was behind the crucial events of August 1953, the gathering in the morning of the pro-Shah crowd in the bazaar and the mobilization of the army units that joined in the demonstrations later in the day—but rather royalist officers in the Tehran Garrison and Muslim clerics, in particular, the Grand Ayatollah Boroujerdi in Qom, who had decided that the drift of events under Mosaddeq was dangerous to Islam.[14]

One last point that I want to make is an elaboration on my earlier statement, “If Iran could have prevented its second revolution, the opportunity was lost under former President Richard Nixon.” During this period, the U.S. government finally had an understanding of the geopolitics of the Middle East. They were given credible intel that stated how Iranians were increasing growing discontent and it would become a problem over time.

“By the time Nixon took office, the Shah had greater control of his society, and his White Revolution was clearly producing results, but the CIA was still documenting ample signs of discontent. This was Nixon and Kissinger’s biggest failure: They persistently ignored mounting evidence that the Shah’s regime might be less stable than they assumed.”[13]

This was the last true opportunity to course-correct Iran. The Shah was receiving large amounts of weapons as part of an ongoing deal with the United States. He was also a Cold War asset who was given preferential treatment. After over 20 years in power, his belief was that he could overcome any impending obstacles. Carter would only learn about this over three years later in 1977.

Kermit “Kim” Roosevelt Jr Source: Unknown

Hang The American Puppet

Former President Jimmy Carter’s mistake was in not understanding or taking the initiative to act while the political levy was breaking. The realization of this was only a few months before the Ayatollah’s return in February 1979. If he did act, what exactly could he have done? Depose a leader of an allied country and install another “American puppet”?

What I believe makes Carter the perfect fall guy is a campaign speech given in 1976 in which Iran is mentioned as a country “in which America should do more to protect civil and political liberties.” Yet U.S. intervention to right the ship was not a possibility. There was a belief within the intelligence community that the Pahlavi Autocracy would last into the 1980s before it either crumbled or an assassination was successful.

As previously stated, the Shah had always been able to steer the ship back on course. This is evident in how he spoke to Carter shortly after he came in to office. The Shah treated the President like many of his predecessors, as someone who needed to be schooled in the politics of the region. When Carter, during a state visit by the Shah on November 15, 1977, remarked in private about commencing a dialog with dissidents and easing up on repressing his people, the Shah’s response was, “No, there is nothing I can do. I just enforce the Iranian laws, which are designed to combat communism.” Avoiding Khomeini’s wildly popular ascension at this stage was not possible.

“Two media-savvy Iranians living in the United States, Ebrahim Yazdi and Sadeq Qotbzadeh, understood that Khomeini had a great opportunity to take advantage of the political opening. But first they had to sanitize the Ayatollah and sweep aside his inflammatory opposition to anything but a rigid theocracy. Khomeini rarely concealed his contempt for liberal norms. Still, in the unusual atmosphere of 1978—when many Iranians were reclaiming their traditions—it was easy to believe in Khomeini’s Islamist vision.”[15]

Yet as protests started in Tehran in the summer of 1978, the Shah believed he had a firm grip on the situation by initiating a liberalization program. Yet as the protests increased, he stated, “Nobody can overthrow me. I have the support of 700,000 troops, all the workers, and most of the people. I have the power.”

Months later after the Shah’s departure for medical reasons, Bakhtiar who was the acting prime minister (Jan–Feb 1979) did not fair well. The following comments include a declassified report from Secretary of State Cyrus Vance to President Carter that highlights this fact.

“Most of the liberal and nationalist opposition, who in other circumstances would have been a natural constituency for Bakhtiar, had thrown in their lot with Khomeini, believing that he would bring genuine democracy to the country and that there must be a clean break with the past.”[16]

“Bakhtiar has told us that he is now less optimistic about filing all the seats in his new Cabinet. A key figure, General Djam, had declined to join the Cabinet; without Djam, military support cannot be assumed. When he talked to Bill Sullivan (ambassador to Iran) today, the Shah was not very optimistic about Bakhtiar’s chances for improving the situation.”[17]

Stansfield Turner, then head of the CIA, made a controversial comment, “Iran is not in a revolutionary or even a pre-revolutionary situation.” He became shortly more alarmist as February of 1979 approached. “As a result of the lifting of constraints, political expression by a wide variety of groups, loyal and disloyal, has mushroomed beyond the ability of the country’s enfeebled official institutions to cope.”

Events were simply transpiring too quickly to assess and act upon. A Top-Secret White House Memorandum for the Record dated January 3, 1979, reveals how late they were in trying to find suitable options.

“The Carter Administration finds itself at a critical moment of decision in whether the Shah should stay or go. The White House has faced huge pressure from Republicans, notably long-time backers of the Shah like Henry Kissinger and David Rockefeller, to solidify U.S. support for him. Secretary of State Cyrus Vance and CIA Director Stansfield Turner make the argument for removing the Shah. Their belief is that reinforcing the Shah’s decision to leave the country would give newly appointed Prime Minister Shapour Bakhtiar a greater level of success. (18)

Admiral and Former U.S. Director of CIA Stansfield Turner’s ideas on how to revamp the agency. (23 May 1995) Source: AP News

Conclusion

The question of whether former President Jimmy Carter’s Middle East foreign policy (1977–1981) failed Iran is still a hotly debated topic. Events following the Iranian Revolution of 1979 make Carter’s inaction prior to the Ayatollah’s return both frustrating and unclear to comprehend. The Iran Hostage Crisis (1979–1981) and subsequent Iran–Iraq War (1980–1988) further muddy the waters, which over time have become even murkier as we edge closer to the 50-year mark.

This overview of the late 1900s to 1979 served three functions. The first is a charting of events that serve as highlights as to where the modern Iran would like to return to as far as democracy and political discourse. The second is the tragedies that steered the country off course. The third is the level of foreign intervention involved in the development of the country.

The image of the Shah being a hapless victim throughout these events does not align with the information before us. He navigated political discourse in the Middle East for decades during a time when even the hint of cozying up with the Soviet Union would have been disastrous. Yet despite this, he had an ongoing weapons deal that the United States attempted to decrease in the decade leading up to the Revolution of 1979.

The elephant in the room is that he allowed for the increase and radicalization of Islam. Instead of taking a more proactive approach like Mustafa Kemal Atatürk and his dealings with religion, he allowed it to grow until there were no real options for frustrated Iranians to get behind. He disapproved of any real political thought even within his circle.

In the end, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi’s actions led to the Revolution of 1979, not the actions of former President Jimmy Carter.

President Jimmy Carter and Mohammad Reza Pahlvai, The Shah of Iran. Toast on New Year’s Eve 1977 Source: Unknown

Sources:

[1] “Why Jimmy Carter Owes the Iranian People an Apology,” Daftari, Lisa, Newsweek, 7.8.23.

[2] America’s Great Game—The CIA’s Secret Arabists and the Shaping of the Fattahi, Kambiz Modern Middle East, Wilford, Hugh, p. 167. 2013.

[3] Iran: Between Two Revolutions. Abrahamian, Ervand, p. 522. 1982.

[4] “Two Weeks in January: America’s Secret Engagement with Khomeini,” Fattahi, Kambiz; BBC News. 6.3.2016.

[5] Worlds Apart: A Documentary History of U.S.–Iranian Relations, 1978–2018; Byrne, Malcolm; Byrne, Kian, pp. 24–26.

[6] Iran: Between Two Revolutions, Abrahamian, Ervand, p. 80, 120. 1982.

[7] The Last Shah: America, Iran, and the Fall of the Pahlavi Dynasty; Takeyh, Ray, p. 8; 2021.

[8] Iran: A Modern History; Amanat, Abbas, p. 494; 2017.

[9] Mohammadmossdegh.com/biography

[10] America’s Great Game: The CIA’s Secret Arabists and the Shaping of the Modern Middle East; Wilford, Hugh, p. 163. 2013

[11] Iran: Between Two Revolutions, Abrahamian, Ervand, p 459, 461, 462. 1982.

[12] The Last Shah: America, Iran, and the Fall of the Pahlavi Dynasty; Takeyh, Ray, pgs. 169,181 ; 2021.

[13] lbid

[14] America’s Great Game: The CIA’s Secret Arabists and the Shaping of the Modern Middle East; Wilford, Hugh, p. 167. 2013

[15] The Last Shah: America, Iran, and the Fall of the Pahlavi Dynasty; Takeyh, Ray pp. 213. 2021.

[16] Khomeini: Life of the Ayatollah; Moin, Baqer; p. 205, 2000.

[17] White House Memorandum for the President. Secretary of State Vance, Cyrus; January 2, 1979.

[18] Worlds Apart: A Documentary History of U.S.–Iranian Relations, 1978–2018; Byrne, Malcolm; Byrne, Kian, p. 21.

The Last Shah: America, Iran, and the Fall of the Pahlavi Dynasty; Takeyh, Ray, pp. 168, 196, 197; 2021.

[19] Iran: Between Two Revolutions, Abrahamian, Ervand, pp. 459, 461, 462. 198

Interested in learning more about Mustafa Kemal Atatürk? Click below.