The Pact of Forgetting (España)

Spaniards, Generalissmo Francisco Franco has died!

Poster of Falange Española (Spanish Phalanx) a Spanish political organization of fascist inspiration.

There is a Saturday Night Live (SNL) news sketch dated December 13, 1975, in which the original anchor, Chevy Chase, begins his newsreel by stating that “Generalissimo Francisco Franco is still dead.” From there on, he continues with his routine of making jokes and comments in regards to the then current news. Toward the end of his mock report, he makes the following remark, “As a public service to those of our viewers who have difficulty with their hearing, I will repeat the lead story of the day,” Fellow comedian Garret Morris appears as the headmaster of the New York School for the Hard of Hearing, and he repeats Chase’s announcement in a louder tone, “In our top story tonight, Generalissimo Francisco Franco is still dead!”

The joke is that Franco had passed away almost three weeks earlier, but his presence was still felt amid the disbelief about his death. Now almost 50 years later, the joke still stands as Franco still looms over the country.

Saturday Night Live News Sketch. El Generalisimo Francisco Franco Still Dead, 1975

Favoring the Rich

“¿Por qué a los Españoles les cuesta tanto distanciarse de Franco?” “Why is it so hard for Spaniards to distance themselves from Franco?” My lead-in question was direct. Considering that I was addressing a difficult topic, I hoped to get right into the conversation . However, more often than not, the response I received went nowhere. Yet one brief conversation, with an interviewee that wished to remain anonymous, stayed with me:

Entrevistada: “Franco fue un ditador mas feroz que Pinochet en Chile. Asesino a varios miles de españoles durante 40 años hasta poco antes de morir. Amaso una inmensa fortuna familiar que ha enrriquecido hasta a sus bis nietos...ladron que aun afecta a España. Son de extrema derecha y te pueden ha er daño. Cuidado con ellos.”

Translated into English:

Interviewee: “Franco was a more ferocious dictator than Pinochet in Chile. He murdered several thousand Spaniards over 40 years until shortly before his death. He amassed an immense family fortune that has enriched even his great-grandchildren... a thief who still affects Spain. They are from the extreme right and can harm you. Be careful with them.”

Thibert: “I have never heard it said that Franco was worse than Pinochet. The comparison puts Franco in a better perspective, especially since they were friends. Therefore, this causes more confusion. Why take until now to end this chapter of the Falange (Franco’s single-party government), the Civil War, and the Dictatorship? Yes, there are differences in how both dictatorships ended, but Chileans openly hate Pinochet and have always been outspoken.”

The Spanish people remain silent as if his ghost still haunts them:

Entrevistada: “Pinochet y Franco fueron sangrientos. Asesinos y al primero los Chilenos pudieron sacarlo Pero Franco murio siendo Dictador y mandando a matar desde su Lecho de muerte A españoles dirigentes de Izquierda. La derecha fran quista sigue defendiendo a sus seguidores Y favoreciendo a Los ricos e impidiendo ayudar a los que luchan por u a democracia real.”

Translated into English:

Interviewee: “Pinochet and Franco were bloody assassins and the Chileans were able to remove the former, but Franco died as a dictator and ordered the killing of Spanish left-wing leaders from his deathbed. The Francoist right continues to defend its followers, favor the rich, and prevent support for those who are fighting for a real democracy.”

Our conversation was coming to an end. We concluded with a promise to continue later. The truth was that I had a clear idea of how España arrived to this point. It involved compromise and letting go to move forward. It was a conscious decision made between the newly elected Democratic parties and the remaining Francoists after Franco’s passing.

Augusto Pinochet meets King Juan Carlos I, 1975

Operation Salmon

Prior to Juan Carlos I accepting the throne in España (Spain) on December 15, 1975, the Spanish Crown had not been on the head of a royal since Alfonso XIII (1931). Throughout Franco’s dictatorship, the monarchy was sidelined in favor of Francoism, which made its namesake the center of all political decisions. A bit of irony here since it was Alfonso XIII who allowed Franco to rise to power through the National (Spanish) Army.

It is important to highlight how influential Franco was to the development of Juan Carlos I. From his education to his military career, he was molded to continue the royal Franco legacy into the next generations. These efforts were made to avoid what Franco wrote about in a private note in 1964, “for the nation [not] to fall into the hands of a liberal prince who would act a bridge toward Communism.”

At one point, the process was referred to by the Minister of Foreign Affairs under Franco, Laureano López Rodó, and Prime Minister Luis Carrero Blanco in 1963 as Operation Salmon because it required the patience of a salmon fisherman.

Earlier attempts in the 1940s by members of Cortes General (Congress and Senate) and high-ranking military officials to reinstate the monarchy are a masterclass in how Franco stayed in power for so long. Ignoring petitions by stating “that he never received it,” then speaking to each person individually until they saw his perspective is how he kept the government, military, and any opposition firmly invested in his success.

The decision to finally choose the heir to the throne had taken decades. Originally intended for Don Juan Carlos (father to Juan Carlos I), the decision required constant check-ins, approvals, and tests of loyalty, which during this time actualized that Franco would not live forever. Parkinson’s disease was a visible part of his life during his later years, which put expediency behind the decision-making process. The result was the 1969 Organic Law of the State (Ley Organica del Estado), passed in 1966, limiting Franco’s governmental powers by allowing a “Chief of Government” to manage the day-to-day affairs and recognizing Juan Carlos I as the successor.

To say that Juan Carlos I was initially disliked is an understatement. To say that he was incredibly lucky is another. By 1975, Prime Minister Carrero was dead, assassinated years prior. The then current generation never knew the Civil War, WWII, or the hunger that followed. They knew tourism, new thoughts, and pop culture. They saw a king who was noticeably moving away from Francoism and a democratically elected prime minister (Adolfo Suarez) who was flawed but was also taking them back to a constitutional monarchy that allowed for the return of multiple political parties.

The old guard was dying or dead. It was time to move on, but the national memories were preserved in statues and monuments and the Falange faded into the background.

Franciso Franco (center left) with Millán-Astray (center right), founder of the Spanish Foreign Legion. Morocco. Date Unknown

Rising Star

Based on his exploits in North Africa (Morocco), Francisco Paulino Hermenegildo Teódulo Franco Bahamonde became the youngest ranked general in the Spanish Army. As a member of the infantry and cavalry units (1912) and Indigenous Regular Forces (Grupo de Fuerzas Regulares Indigenas), Franco climbed up the ranks in the years prior to the Rif War (1921–1926). As France and Spain split the region into their fiefdoms, various tribes staged attacks on both nations, prompting the creation of individual battalions that used native fighters to fill their ranks. In this setting, the legend of his bravery began and took root, later turning into stories that Franco repeated ad nauseam to the point that Hitler became tired of hearing them.

Earning the respect of soldiers on and off the field, this was the best period of Franco’s life. His climb up the ranks with his heroic actions earned him his own unit named First Regiment of Regulares of Melilla and the Cross of Military Merit. Through native rebellions and geopolitics, he became highly sought after. His status became intensely mythical after a military operation in June 1916. Only a year after the Anjera tribe staged a rebellion in what is now the region between Ceuta and Tangier.

Now commanded to charge deep inside the rebels’ territory (El Biutz), Franco led the attack. After a soldier was killed, he picked up his rifle and continued fighting until he took a bullet to the abdomen from a machine gun—a wound that should have killed him. Years later, his daughter, Maria del Carmen Franco y Polo, 1st Duchess of Franco, Grandee of Spain, and Marchioness of Villaverde, recounted the tale from the perspective of her father.

“When medical personnel reached him, however, they said, “No, not this one. He’s gut shot. No point evacuating him to the medical truck. He’ll die shortly. My father then said to his Moroccan assistant that he did not feel as though he were dying and had no intentions of dying on such a nice day. He told him, ‘Grab your gun and point at these chaps until they get me back to the truck.’”

After recuperating, he became the youngest major in the military at 24. A cycle of earning distinctions, assignments within some of the toughest units, and praise from his military superiors and King Felipe supported his ascension until he could go no further up the ladder. Even the courtship of his future wife Carmen Polo, who later became the driving voice behind the strict religious and societal structures during the dictatorship, was second to his military career, despite the reservations of her family. She was the ideal partner for a man who himself never indulged in any vices other than a single glass of wine during dinner.

During his second tour in Morocco (1920–1926), he was a secondary officer to the founder of the Spanish Legion, Commander José Millán Astray of the tercio or legion that was a unit of tough, stubborn, violent, and adventure-seeking soldiers from mostly Spaniard stock and some from of the region. An example of the extremes taken to prepare the soldiers of this battalion comes from an incident in 1921.

Franco had always thought that military discipline was too lenient. The orders from Commander Astray were to only carry out executions after a military trial. When a volunteer objected to this discipline by throwing his rations on the ground and throwing a tantrum, Franco promptly executed him and ordered the other soldiers to march over his body. He was never disciplined for his extreme actions, and no other solider ever challenged him again.

These vignettes into who Franco was and how he maintained order give us a peek at how he created his dictatorship by demanding full dedication, immediate discipline, and loyalty. This mix moved him into the position of major general by the onset of the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939). To draw a comparison with soldiers of the same age, his compatriots at the time were still lieutenant-colonels.

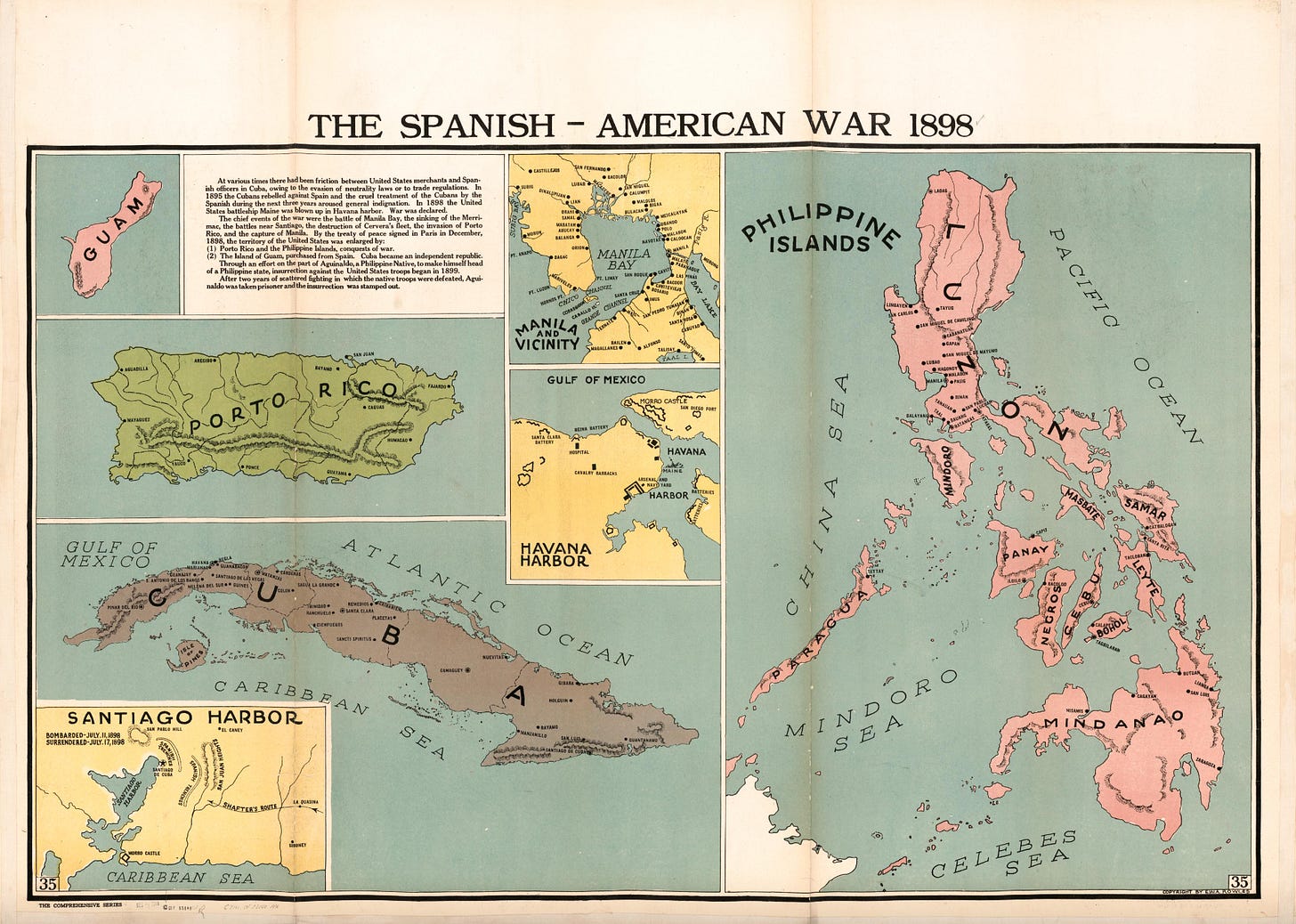

Map of the former Spanish Colonies of Puerto Rico, Cuba, Guam, and The Philippines, 1898

The Other Dictatorship

To understand modern España means understanding the politics of the late 19th century. Personally, I have felt that this period is largely ignored, except for a glance at the Spanish–American War of 1898, which removed Puerto Rico, Cuba, Guam and The Philippines from the orbit of what was left of an almost dead Empire minus its colonial possessions in Africa. Recounted by Charles J. Esdaile in the book, Spain in the Liberal Age, “For the Spain of the 1890s already contained within it the outlines of the ‘two Spains’ that were to fight the Civil War the 1930s.” He continues to explain that, “many elements of the Church and the army, in particular, were developing clear signs of a Messiah complex that eroded not only their own loyalty, but also that of the increasingly freighted landowners and entrepreneurs who dominated society and economy alike.”

On the other hand, there was a growing wave of popular unrest that was prone to manipulation, badly led and by no means united, foreshadowing the general revolutionary movement that in 1931 produced the Second Republic and rang the death knoll of caciquismo.

Spain was disintegrating by the early 20th century. The dictatorship of General Miguel Primo de Rivera (1923–1930), was supported by King Alfonso XIII, and the army was a step to preemptively save España from itself. To “clean” it by dismissing the old politicos (under Presidente Manuel Garcia Prieto) who offered nothing more than vague promises and few reforms. Primo was to return the government to a pristine state after a brief military rule to ensure that this new start was on a new foundation. Instead, it further fractured, alienating members of the military and government.

By 1930, Primo de Rivera was forced to resign, with few accomplishments, but unfortunately the damage was done. Subsequent leaders General Damaso Berenguer and Admiral Juan Bautista Aznar could not keep the country together. As the civil war loomed, Alfonso XIII left the country, losing the confidence of any of those still invested in the monarchy.

Jumping forward to the official Civil War (1936–1939), after the failure of another attempt to unify of the country, the Nationalists, which were composed of the Spanish military with aid from Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy, and Republicans (Loyalists), which were composed of civilians, volunteer brigades from multiple countries including Europe and the United States, and aid from the Soviet Union went to war.

Starting with military uprisings by the Nationalists in small towns throughout Spanish Morocco, and the islands, battles spread to the mainland as violence, murders, and executions on each side increased, leading to a full-on war that placed General Franco as its head and Francisco Largo Caballero as the new head of government.

General Miguel Primo de Rivera, date unknown

The Falange Single-Party System

My first visit to Toledo was in 2008. Not knowing anything about the area, I noticed the Alcázar (Castle) of Toledo in the distance, and began to anxiously hope that it was our destination. Then I was elated when we parked near the main path.

Once inside, I studied the ancient brick and large stone walls where the Toledo blacksmiths fired up their kilns. I overheard the guides recounting the medieval battles and heroes from the Roman Era to the 16th century history. It was years later that I realized that the details of the more recent stories were being glossed over by only mentioning the walls damaged by weapons fire during the onset of the Civil War.

Today, I wonder if the Siege of the Alcázar (July–September of 1936) was part of the forgetting and moving away from the past? How exactly do you spin the execution of a 16-year-old boy by the Republicans to get the Nationalists, lead by the boy’s father, Colonel José Moscardó Ituarte, to surrender?

The end of the war brought mass executions of the Republicans. Many of those bodies were dropped in large burial plots or disappeared. Some of them have been unearthed fairly recently.

“Graveyard 112, as the site is known, is located in Paterna, a town on the outskirts of Valencia. According to Parra, researchers believe that at least 2,238 prisoners of the Franco regime were executed in the area and buried in 70 mass graves that were then sealed with quicklime,” according to Katz, Brigit in “Archeologists Open One of Many Mass Graves from the Spanish Civil War,” Smithsonian Magazine, August 30, 2018.

Side Note: As of mid-2023, regional funding for the exhumation project was halted by the Conservative People’s Party (PP) and Vox as part of the “Law of Concord” that requires individual families to cover the costs for exhumations.

Other graves were ignored until the burden became too heavy. In the Plaza del Moral (former Plaza del Generalissimo) in the pueblo of Poyales del Hoyo, gathered volunteers in 2002 to excavate and give the bodies of their former neighbors a proper burial.

“Look, this must be one of Valeriana’s teeth. They smashed her skull. We couldn’t find all the bits. We looked for the skeleton of an unborn child, but we could not find all of that either,” (Giles Tremlett, Ghosts of Spain, p. 21).

Shortly after the war, Falangist solders lead by Angel Vadillo, nicknamed Quinientos Uno (501) for his total number of kills, came to Poyales del Hoyo to dispatch any Loyalists or anyone with Loyalist leanings. Unfortunately, Valeriana Granada, Pilar Espinosa, and Virtudes de la Puente all met that criteria and were murdered on December 26, 1936.

One of the largest and most controversial burial sites is the Valley of the Fallen where over 40,000 bodies were placed along with Franco. This was a misguided intention by Franco, along with his final message to the los vencidos (defeated), to bring a conclusion to the war. Instead, this place has turned into a rallying point for Franco devotees and Right-Wing Nationalists to pay their respects to the Falange and the man they believe brought order to the country.

“I like coming here; it makes me feel peaceful,” Cristina Cabanas says. “I love this place—I’ve always been pro-Franco,” Gue Hedgecoe, “Spain’s Monument to Franco: A Divisive Reminder,” Al Jazeera, February, 2015.

The controversy that has been ongoing since the late 2000s with the enactment of law 52/2007 (Historical Memory Act or Democratic Memory Law), and addendum in 2018 to void legal decisions made during the dictatorship, was ramped up in the mid-2010s when activists, including Odon Elorza of the then Congress petitioned to have the site converted to an education center. In 2019, the ruling Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party (PSOE) government under PM Pedro Sanchez requested that the body of Franco be reinterred at another site and for his family to make preparations. Later that year, Francisco Franco was exhumed and moved to a private location. Earlier that same year, the body of Falange Española founder, Jose Antonio Primo de Rivera was removed and reinterred in a cemetery in Madrid.

The removal of other members of the Falange from other sites, such as General Gonzalo Queipo de Llano, who was buried in a church in Seville until November 2022, have been discreetly removed from their resting places and moved elsewhere out of view of the press and their victims.

Protests over Franco-era crimes, 2013

Years of Consensus

Franco’s dictatorship is often difficult to categorize. The reason is that it falls into this strange space of taking on many characteristics of a dictatorship, but it doesn’t quite ring the same. One can argue that the relations to Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany were for survival since Franco never officially joined the Axis.

A closer look highlights that joining was not possible. Economic and societal collapses after the Civil War left España in a position where it needed more aid than it could give. The Marshall Plan that would go on to revitalize Europe was not given to España.

After the war, Argentina’s meat exports helped the country during its time of need. Another area that was lacking was a societal class of poets, artists, journalists, politicos—all of whom were exiled from the country. Those who had fought in the war were either in a mass graves or a prison. The Fuero de los Espanoles (Charter of Spaniards’ Rights) was suspended, and some of the middle class finally saw how severe life had become.

Over time, Spaniards were forced to tolerate their situation in a period referred to as the “years of consensus” that lead to apathy.

“It is typical of dictatorial regimes that they either mobilize ordinary citizens to support them or demobilize them as through passivity were a necessary response for survival. Fascist regimes always mobilize and the Franco regime did so right from the start; throughout all its life, when it thought it was in danger, its response was to mobilize support. Usually this took the form of a kind of ‘docile anarchy’ which worked by cultivating an inarticulate passive society” (Javier Tusell, Spain: From Dictatorship to Democracy, p. 14).

Although the Falange was the single party’s voice, other groups became prominent during this time. From the Catholic Church, monarchists, and dissenting military again highlighted how Franco maintained power.

“His greatest skill, the manipulation of his supporters, was also a diminishing asset. He had handled the rivalry of the Falange and the monarchists in the army up to 1945 and of the Falange and the Catholic monarchists in the post-war period with preferment and jobs…. Younger men less bewitched by the aura of the Caudillo began openly to jockey for position .” (Javier Tusell, Spain: From Dictatorship to Democracy, p. 16-17).

In the end, it was not a protest, a battle, or a revolution that saved España. The outside world was creeping in, and the propaganda of Manuel Fraga Iribarne, who was head of the Ministry of Information and Tourism, was crafting the image that drew in visitors and attempted to keep to the strict moral and societal codes of Francoism. From Britania (United Kingdom) and other parts of Western Europe, the greatest benefit to the economy that edged it farther away from conservatism were the throngs of tourists along the Costa del Sol.

Costa del Sol Beach Resort, 1960s

Democratic Memory Law

Presidente Major General Juan Chicharro Ortega’s assistant responded to my mail only a few hours after I sent a request to interview him. As Executive President of the Fundación National Francisco Franco (FNFF), an organization formed in 1975 to preserve the memory of Generalissimo Francisco Franco, I did not expect to receive a response, especially during this time.

Since the Law of Democratic Memory (2007) was approved, the Foundation has attempted to work within its limits. This is a seemingly impossible task due to the nature of the Foundation. Nonetheless, Major General Chicharro, who comes from a family with a political and military background and has also been an aide to Juan Carlos I, has stated that this is an attempt “to silence all dissidents of the policy of the government of Prime Minster Pedro Sanchez” and that dismantling the Foundation is “a violation of the constitution.”

Thibert: “Presidente Major General Chicharro, thank you for making time to answer my questions. I am aware that you are a very busy person, so I am appreciative that you have allowed me the opportunity to interview you. Please note that my questions are to understand the Francisco Franco Foundation’s current role and how and if it has evolved since its founding by 226 members on October 8, 1976.”

Thibert: “Let’s start with you. How did you get the position of president of the Foundation? Did you have a personal connection to Franco?”

Major General Chicharro: “I do not have a personal connection with Franco. When I retired in 2015, I was asked by a friend who belonged to the Foundation if I would be the president. I had my doubts, but finally I said yes because I thought that somebody had to tell the truth of who Franco was against all the lies that were being spread.”

Thibert: “What has the Foundation accomplished since it’s founding? What would you say are its major achievements?”

MGC: “The Foundation was created in 1976, and its goal was, and is, to tell the younger generations what he did for Spain and what his legacy is. Our major achievement has been to keep his personality alive and that the Spanish people can hear about him and not forget what Spain was in 1940 and what it was in 1975 when he died. Quite a different country in many ways.”

Thibert: “Tell me about the initial years of the Foundation? Can you provide some insight on its growth under King Juan Carlos and the transition period?”

MGC: “The initial years were an easy task. Not any problems. The problems started when those who began to remove old and already forgotten wounds—the socialist, communist, and many others whose fathers and grandfathers were lost in the war—began to blame Franco for all that happened during the transition period.””

Thibert: “How does the Foundation survive financially? Are there any donors? If so, can you name any of them? Is there any assistance from the Spanish government?”

MGC: “We have almost 2,000 affiliates who pay a small amount every month, and yes, we have several donors. We don’t have and never have had any government assistance. This is a private institution.”

Thibert: “In the 2008 book Ghosts of Spain, by Giles Tremlett and a 2018 article from Natalia Junquera both mention the Foundation and how it makes it difficult to access the up to 3,000 documents related to Franco. Is this true? The Foundation site lists “the Rules for Access to the Historical Archive” but is anyone who follows your procedures able to access the entire archive unheeded?”

MGC: “Yes, we have thousands of documents related to Franco and all of them can be read and used by anyone who asks for them. Those who say the contrary are lying. And of course, those who follow the rules have access to all of the documents.”

Thibert: “In your opinion, are the ghosts or wounds of the Civil War still present in today’s society? If so, can you describe how the Foundation assists in healing these wounds?”

MGC: “After any civil war, wounds and ghosts need time, even generations, to heal, but in 1975 most of them had been forgotten due to the fact that when Franco died, the poor Spain of 1936 had become a rich country and a new middle class had been created. The biggest social/economic transformation of our history had been performed. What did we do? We remembered and told the real truth, using our means, limited, yes, but obviously efficient considering that the socialist party tried to illegalize us.”

Thibert: “You stated in a radio interview in July 2021 that “When Spain is breaking up, Franco Is always to blame.” Is this still the case, and if so, why is Franco specifically to blame?”

MGC: “There is also something that the communists never forget. They were defeated by Franco in the war and defeated even more during the peace time of Franco’s regime. This is one of the main reasons why he is continuously blamed.”

Thibert: “Tell me your thoughts on the 2007, Law 2/2007 more commonly known as the Historical Memory Law that is behind the slow closure of the Foundation. There is a mention on the Foundation’s site of attempts to work within the law as well as changes to your statutes. Can you elaborate on how you have tried to amend the Foundation to work within the law?”

MGC: “The ‘Ley de Memoria Histórica’ and the ‘Ley de Memoria democrática’ are among the ways these socialist and communist governments use to change history .”

Thibert: “In your 2021 interview with researchers Sarah Barbier and Romain Calmejane, you make the statement, ‘It speaks of the victims of the Civil War but of the Republican side; it does not speak of the victims of the other side, of which there were many as well and they forget about them,’ This is in reference to the Historical Memory Law. Please clarify.

MGC: “To answer and clarify that the LMD does not pay attention to all the victims’ needs only a reading of several writers and historians who tell the truth of all the atrocities that the socialists and communists did during the war.”

Thibert: “In the same article, you make reference to ‘cancel culture’ and how ‘history must be studied as a whole from all points of view.’ I cannot help but notice that the site does not mention any of wrong turns the Franco government took or giving asylum to over 100 Nazis. Does the Foundation provide all the points of view of history or only the winner’s perspective?”

MGC: “Asylum to over 100 Nazis? I will not deny this, but it’s something that must be seen under the circumstances of a time that was really difficult.”

Thibert: “You mention within a post on the Foundation website that other Foundations such as the Francisco Largo Caballero Foundation and Federico Engels are not being affected by the Historical Memory Law. Can you elaborate on why?”

MGC: “Yes, there are several foundations supported economically by the government. Most of them are Marxist and, of course, they are not affected by a law established by Marxists. It’s not strange that these things happen. Try to illegalize our Foundation and maintain another one with the name of Largo Caballero who was Prime Minister at the same time that thousands of innocent people were murdered in Paracuellos del Jarama is really sectarian and totalitarian.”

Side Note: Attempted to reach a representative from the Francisco Largo Caballero Foundation for comment. To date, no response has been received.

Thibert: “Does this mean that the Franco Foundation is being specifically targeted?”

MGC: “Of course, the Franco Foundation is being specifically targeted. We are probably the only Institution that tries to tell all the murders that the socialists and communists committed. Obviously, that is one of the reasons they try to close our mouth.”

Thibert: “I have noticed that the general press has not reached out for your opinions. Is this true? Has your perspective/voice been ignored?”

MGC: “Of course, our perspective is ignored for the same reasons explained above.”

Thibert: “When I speak to Spaniards and ask ‘Who was Franco to you?’ I receive a variety of answers. So, I am obliged to ask a similar question, ‘Was Franco a leader who saved the country and brought stability after the Civil War or was he a dictator who was lucky that the consequences of his actions did not catch up with him?’ Please elaborate why.”

MGC: “Franco was a leader who won a war against a coalition of socialists and communists supported ideologically by Stalin. If Franco had lost the war, there are no doubts that Spain would have fallen in the hands of Stalin and what would have happened in Europe and in WWII in such a case?”

“Franco kept Spain out of WWII. What would have happened if he joined Hitler? Probably the destiny of the war would have been completely different if Hitler occupied Gibraltar. Churchill was well aware of this as can be read in his memoirs. Franco saved Spain from entering into WWII and who later transformed Spain in such a way that when he died, we were the eighth most industrialized power in the world.”

Thibert: “In your opinion, what would the country be losing if the Foundation is formally closed? Can it survive in another form?”

MGC: “If the Franco Foundation is closed, no other institution will exist to tell the truth against all the lies one can hear every day in the medias in hands of this government.”

Thibert: “Is the Foundation suing or attempting any legal action against the current government? If so, how has this affected the Foundation financially?”

MGC: “Of course, we will fight legally with all our means against those who try to illegalize us.”

Thibert: “I noticed there has been some back and forth between the current government of Pedro Sanchez, the Foundation, and the Benedictine monks regarding the Basilica of the Holy Cross of the Valley of the Fallen. Can you elaborate your view on why changing the site would be a negative? This is especially important when it appears that many of the bodies of victims within the tombs belong to families who want closure regarding the death of loved ones. I include Fausto Canales whose father Valerico Canales was one of the individuals who is in a tomb (National Public Radio, “Spain to Uncover Past in Valley of the Fallen,” November 9, 2009).”

MGC: “The Basilica of the Holy Cross is a sacred place and, accordingly, only the Catholic Church and its hierarchy have the last authority regarding it. The government can’t do anything, whatever they say, without the approval of Rome.”

“You have the wrong idea about how many bodies are there. Let me tell you that the heirs of only about 100 of the 33,842 bodies have asked for permission to move a relative’s remains. I have nothing against their wishes, but they are only a few in number.”

Thibert: “You reached out to the president of the Community of Madrid, Isabel Diaz Ayuso, after her August 2024 visit to the Basilica of the Holy Cross of the Valley. Have you been able to connect with her? What are you hoping this connection is able to provide?”

MGC: “Yes, we have connected with Ayuso, and she has told has that she doesn’t have any competency on this matter (we don’t agree), but she will try to do her best to influence those who she believes are competent in order to preserve the Valley.”

Thibert: “If the Vox political party got into office during the previous election, would the Memory Law be an issue?”

MGC: “I am sure that if VOX gains power, it will eliminate such an unconstitutional law.”

Thibert: “What do you think the majority of Spaniards will think of Franco at the 100-year anniversary of his passing?”

MGC: “I am sure that Franco and what he did for Spain will be recognized sooner or later. When? I don’t know but that’s for sure. It’s just a matter of time.”

Franco's exhumation: Former Spanish dictator's corpse moved, 2019

Conclusion

Francoism metastasized within España. Unlike Pinochet or other Latin American dictators from the 20th century, we speak of the Generalissimo and the Falange as if they are still present. In this sense, the move to democracy was a mere interlude to the deep-rooted problems within the country.

You can easily find someone who clamors for those days, despite not being alive or too young to remember what it was like to live under a dictatorship.

It brings concern due to the rise of conservative groups such as the political party VOX, which as of late 2024 has asked for the resignation of current prime minister, Pedro Sanchez, as well as the government. Corruption has been cited as the cause for requesting an immediate election. This action and an increase in far-right groups are cited as being responsible for the rise in hate crimes over the past few years.

Although it has been almost 50 years since the joke was last aired, the Spanish people must be reminded that, “Generalissimo Franco is still dead.”

If only the Spanish believed this to be true.