Is Sedition Undermining or Uplifting Democracy? (History)

The "Democratic" History of Sedition (1798 - 2024)

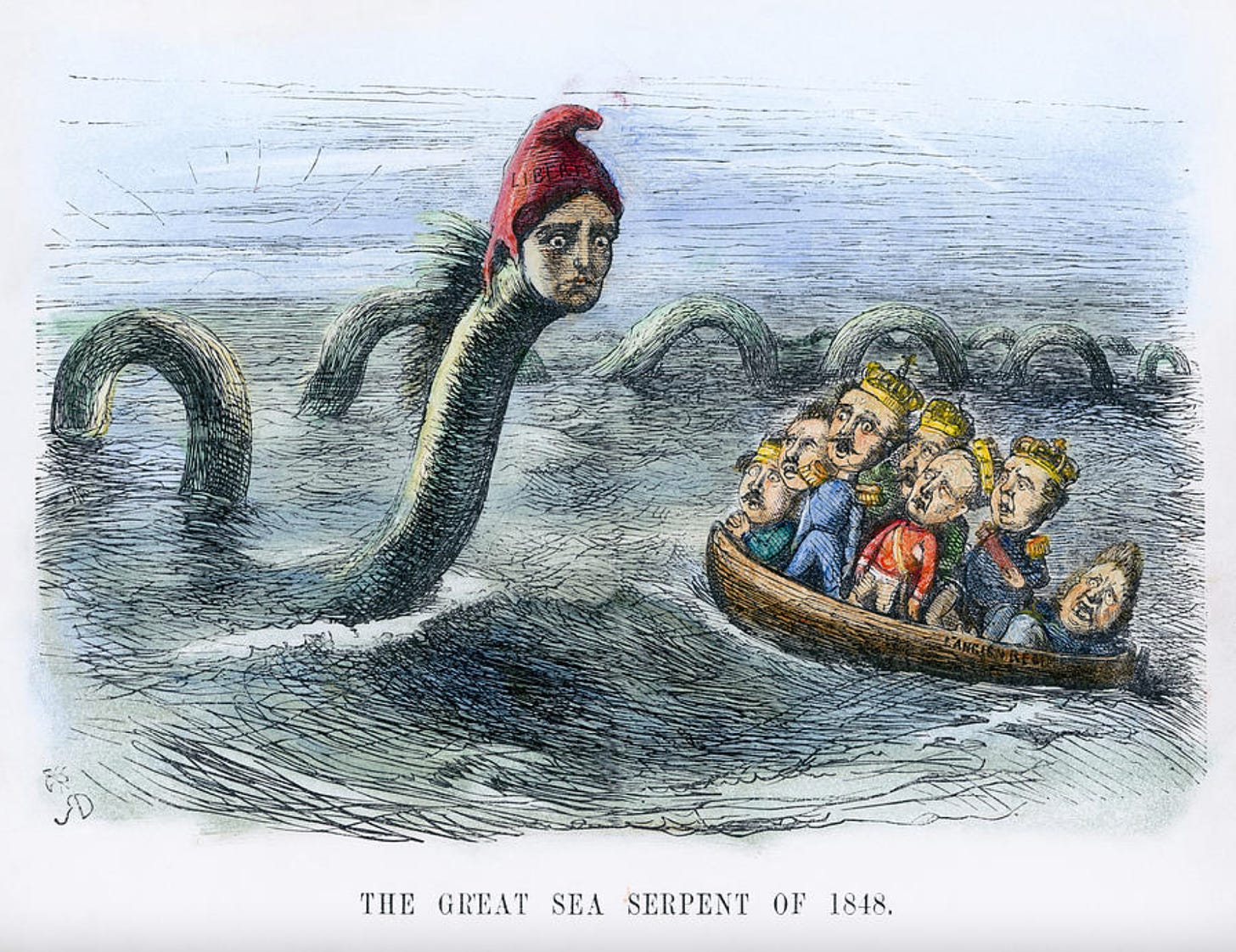

Italian Revolution 1848

Are protests or speaking out against your government acts of sedition?

Reading today’s headlines makes many readers believe that the answer is undermining, as democracies proclaim that their citizens are dissidents when they speak out against wars, public health policies, migrants’ unfair treatment, civil rights, and what constitutes free speech and who funds it.

More often than not, those who speak out are scorned, beaten, placed in jail, or flagged as a potential risk to their government. Some recent examples are protests in Tbilisi, protests on college campuses, protests about Indigenous rights in Latin America, and many others.

Over time, sedition has become a dual tool for the right or for the left to use whenever its usefulness is convenient for governments’ purposes.

For this article, I want to focus on examples of various democratically elected governments that proclaimed their citizens were committing sedition or espionage by speaking out and the laws and acts they used to attempt to stifle these voices.

XYZ Affair inspired this 1799 cartoon showing Hydra-headed French Government demanding money from the Americans at dagger's points.

Seditionary Acts (United States, 1798– )

On January 21, 1793, the High Executioner Charles-Henri Sanson dropped the guillotine on the neck of King Louis XVI of France, thus effectively ending the Ancien Régime (1500–1798). In the struggling young nation of the United States, its foreign policy under President Washington was to stay neutral. Events between the Western European powers, despite pressures to assist France in matters of owed payments, able bodies, and ships went unheeded. When Edmond-Charles Genêt, ambassador to France, came to the U.S. to recruit Francophile Americans (Jacobins), Washington reminded Monsieur Genêt that the treaty between the Americans and the French was with King Louis XVI.

“The Alien Act (1798) granted then President John Adams unilateral authority to deport non-citizens who were subjects of foreign enemies. The Sedition Act (1798) attacked the core of free speech and a free press—the right to criticize the government. The Naturalization Act (1798) increased residency requirements for U.S. citizenship from five to 14 years. The Alien Enemies Act (1798) called for the arrest or deportation of aliens from an enemy power in case of war.” Constitution Center.org

Wars make nations forge their decisions out of fear and concern. Sometimes, wars are due to public hysteria, while at other times, their governments are over-reacting. To be fair, more often than not, wars are caused by a mix of hysteria and over-reacting. For example, the Alien and Sedition Act of 1798 was enacted by a government that over-reached and was fueled by panic.

As war with France seemed imminent, the Federalist Party headed by Adams became concerned that criticism of foreign policies was a sign of disloyalty to the country. In response, the laws that came to be known as the Alien and Sedition Act were enacted to stifle those voices.

Since our focus is on citizens affected by laws of this sort, we are going to examine how these laws affected the nation.

Twenty-six counts of sedition were recorded during President Adams’s single term (1797–1801). During this time, Benjamin Franklin Bache, grandson of Ben Franklin, was arrested for libel in his publication, The Aurora, which stated that citizens should have access to a free press. Matthew Lyons (Vermont-R) was tried for defaming the government by stating that the Sedition Act was unconstitutional and that his writings were not intended to cause harm to the government.

Another journalist, John Callender, was put in prison for nine months for “false, scandalous, and malicious writing” against the President. By design, the act targeted mostly people of the Democratic – Republican Party (1792–1834) and any immigrants who were known to side with that party.

On the last day of Adams’s presidency, a large portion of the Alien and Sedition Acts expired, leaving only the Sedition Act, which is still active as of this writing. This act was used to intern Japanese nationals during WWII and may be utilized to remove migrants from U.S. soil.

Hungarian Revolution, 1848

The Year of Revolutions (Europe, 1848)

If the early to mid-19th century had a motto for good intentions, it would have been Liberté, Egalité, Fraternité. Unfortunately, by 1848, the aspirations of liberty, equality, and fraternity were in a stagnant position that continued into the 20th century.

I strongly believe that if this year of revolutions had gone in a different direction, then Germany, Austria, Italy, and all of Eastern Europe could have avoided a lot of future headaches. If you can allow me to hedge a little with this section, since some of the nations above did not exist until later in the 19th century as well as after the break up of the Soviet Union in the late 1980s, you will see why I felt it was important to discuss this period.

By the 1840s, Europe was still reeling from the end of the Holy Roman Empire (1806), Napoleonic Wars (1801 – 1815), and political decisions that were meant to keep various monarchies in power, such as the Empire of Austria (1804–1867) and the Kingdom of Prussia (1701–1918).

Promises of creating a republic, supporting liberal political reforms, or maintaining a constitutional monarchy were kept out of reach. This forced individual leaders to use various means to dissuade and keep their peoples from gaining political momentum.

“The French capital sent shockwaves across Europe because France’s now well-established revolutionary tradition made it the single most important source of inspiration or fear. The great French revolution of 1789 had been studied carefully by reactionaries, reformers, and revolutionaries alike for lessons and warnings .” Rapport, Mike. 1848: Year of Revolution. 1st edition., Basic Books 2009

In response to growing democratic sentiments, in Austria, the brief government of Baron Franz von Pillersdorf (1848) put into effect a press law that made any written works critiquing the emperor a treasonable act.

In Moldavia, Alexandru Cuza called on military (Russian) support to break up a mob of people who were petitioning for reforms to boost the economy. Several protesters were killed and more than 200 were arrested, dragged down the street, beaten, and subsequently expelled to Turkey (March 1848).

The Kingdom of Naples (Southern Italy) under King Ferdinand (1810–1859) used censorship, secret police, and a ban on public meetings to shift the rising democratic uproar to his favor and avoid promises of a more liberal government despite the election of a liberal parliament (May 1848).

Fear that an uprising of the poor and disenfranchised throughout Central and Eastern Europe after protests and insurrections in Paris, Vienna, and Frankfurt increased the political powers of parliaments and monarchs to stem fears of mass unrest in sacrifice of political freedoms. Groups like the Constitutional Club (Vienna) materialized during this time and fed off this fear, leading to large numbers of members who were more concerned about law and order than crafting new and liberal constitutions.

Father Gavazzi (Italy) and Abbe Felicite Robert de Lamennais (France) used religious publications to make their arguments. Religion was becoming a tool to keep the masses loyal to the old ways paralleling Jesus and the poor but still tied to the monarchy.

An initial promise of freeing the Hungarian peasant class from the robot (slave) system led to rioting on the realization that what gains they did achieve still bound them to servitude. Rioting commenced when their voices were not heard (June 1848), which led to the Minister of the Interior, Bertalan Szemere (1848), declaring a state of emergency (emergency powers) and bringing in the National Guard to arrest peasant leaders and execute various protestors to bring about peace.

Although my review of this period is rather one-sided due to the main topic, it is important to note that protests and riots did get violent but that was the result citizens not being heard or given half promises instead of not taking the first course of action. The subsequent actions of stifling the press, use of the military, and manipulation out of fear were, in my view, extreme responses to the growing demands for liberté, égalité, and fraternité.

Political cartoon 1848

Keeping an Eye on You (UK 1889, 1911, 1920, 1939, 1940, 1989/Malaysia 1972)

In 1790, philosopher Jeremy Bentham wrote that “secrecy, being an instrument of conspiracy, it ought not, therefore, to be the system of regular government…publicity, regular elections and a free press were needed to protect the public from the ‘bullies, blackguards and buffoons’ who might be returned to power.” Unfortunately, by 1833, the thought of a free press, especially in regard to political discourse, led to an injunction on papers discussing relations on Bavaria, Austria, and Prussia.

Similar actions took place in 1837 (Lord Wellesley/Espana) and in 1858 (Ionian Islands Union with Greece). Employing the Larceny Act (1827) in an attempt to punish British Official William Guernsey over the Ionian Islands scandal (British property at the time), the failure to prosecute Guernsey led to stronger measures to keep state discourse away from the public.

By 1889, measures to dissuade espionage by punishing the sharing of government discourse evolved into the creation of the Official Secrets Bill (1889), and by 1911, it was rolled into the Official Secrets Act. In 1920 and 1939, additions were made that expanded on the powers granted by the original act, including the persecution of the press.

“If one wants to find out how to look after one’s children in a nuclear emergency, one can not, because it is an official secret; if one wants to know what noxious gases are being emitted from a factory chimney opposite one’s house, one can not, because it is an official secret,” MP Clement Freud, 1979.

Hence, the problem with the act was that it allowed the English government to declare that almost any printed discussion was espionage. For example, in 1932, a terminally ill government clerk was jailed for six weeks for revealing details of three wills a few hours early. In 1937, two journalists were arrested for not revealing the source of a story published in the Manchester Daily Dispatch. When Home Secretary Samuel Hoare spoke up about it in Parliament, he found himself also facing arrest.

When MP Duncan Sandys shared his plan to ask Parliament about a shortage of anti-aircraft guns, he was threatened by Attorney General Sir Donald Somervell.

Although prosecution under the act was rare, it did happen, especially with the addition of the 1940 Treachery Act that was enacted to protect against espionage during World War II, but it subsequently stayed in effect after the war’s conclusion.

Attorney General Sir Hartley Shawcross went on to use Section 2 of the 1940 Act to warn journalists that they would feel the full force of the law if they were to “betray the honor of their profession by soliciting the discourse of official information.” Following this period, various parts of the act went on to punish cold war spies and the press.

Unfortunately, both World Wars prompted various nations to implemented laws to protect their governments from espionage. Although we are focusing on the United Kingdom’s Official Secrets Act, it is equally important to point out that other major nations had their own versions enacted around this time, such as Australia’s Crimes Act (1914) and the United States’s Espionage Act (1917). Just like the laws created in those nations, these acts stayed on the books far too long. In the case of the United Kingdom, the Secrets Act and subsequent acts stayed on until 1989 when, by this point, the first act was being used to arrest journalists under the pretext that collecting information was equal to spying.

“The 1989 Act replaced the ‘catch-all’ section 2 and created offences associated with the unauthorized disclosure of information in the following categories: security and intelligence; defense, international relations, crime, and special investigation powers, information resulting from authorized disclosures or entrusted in confidence; and information entrusted in confidence to by other states or international organizations .” Cobain, Ian. The History Thieves: Secrets, Lies and the Shaping of a Modern Nation 1st Edition, Portobello Books Ltd, 2016

In creating offenses under these categories, the act distinguishes between current and former employees of the security and intelligence services, and crown servants (e.g., ministers, civil servants, members of the police and armed forces) or government contractors. For crown servants and contractors, the act stipulates that someone can only be found guilty of an offence if the unauthorized disclosure is deemed “damaging.” Provisions relating to members of the security and intelligence services, on the other hand, stipulated that any unauthorized disclosure relating to security and intelligence is an offence. The maximum penalty for individuals guilty of an offence under the act is two years of imprisonment or a fine, or both. In 2015, the Law Commission was asked by the Cabinet Office to review the effectiveness of the laws that protect government information from unauthorized disclosure. Its provisional proposals, published in 2017, have been met with concern, principally on the grounds of public interest defense protections for whistleblowers.

Today, the U.K. has some of the world’s toughest laws when it comes to not only investigating members of government but their own citizens (Investigatory Powers Act, 2016).

Unfortunately, in 1972, Malaysia was inspired by the United Kingdom’s record of making any information, form, or document that pertained to the government an act of espionage. The Malaysia Official Secrets Act (1972) and subsequent versions had the same effect as in the UK and subsequently led to abuse by the government.

“The law is not perfect. It is open to abuse, but you hope to find people who will not break the law, who will obey the rule of law. That is what is important” (Malaysian Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad (1981–2003 and 2018–2020) in 2018 referring to the Official Secrets Act.

Unfortunately, by the time that statement was made, the act was used to jail Vice President of the Parti Keadilan Rakyat (PKR) for 18 months and cover up various government scandals leading to protests and the rise of the multi-ethnic Pakatan Harapan .

As one of their campaign promises, the original act will be amended (Act 88) “to ensure the delivery of public services can be enhanced and to encourage the citizens to be involved in the process of formation of national policies” and a Freedom of Information Act (2018) is still in the works.

Smedley Butler speaks about US politics at Newtown Square in Pennsylvania, Sept 1935

War Is a Racket (United States, 1931)

For those who are not familiar with the title of this section, those words came from a speech by Marine Corps Major General Smedley D. Butler (1931). He spoke out against the U.S. government and various industries that were using the U.S. military to influence foreign governments, including Honduras, Veracruz (Mexico), and Nicaragua (Banana Wars).

As an anecdote after he gave a speech at the Philadelphia Contemporary Club (1931), Butler shared a story shared by a gentleman, later identified as Cornelius Vanderbilt Jr., of how Mussolini ran over a child without halting his vehicle.

“My friend screamed as the child’s body was crushed under the wheels of the machine. Mussolini put a hand on my friend’s knee. ‘It was only one life.’ He told my friend. ‘What is one life in the affairs of the state?’”

Now, at this point, this shared story is heresy, but these events were transpiring while Mussolini-era Italy was looked upon as an example of correct governance. As gossip goes, this story ranked as a geopolitical nightmare as the Italian government proclaimed the story was ridiculous.

Mussolini issued this rebuttal: “I have never taken an American on a motor car trip around Italy, neither have I run over a child, man, or woman.”

Repercussions were swift, leading to the court martial of Butler. Then Senator James T. Heflin put on record that the “court martial seems petty and vindictive, as by contrast Mussolini was a red-handed murderer to whom General Butler must bow down and crawl in the dust and apologize to.” Public opinion backed Butler as an American hero, leading to a formal trial that resulted in his reinstatement of rank and privileges.

After the affair, Butler chose to leave military life by opting for an early retirement. In 1959, Vanderbilt confirmed Smedley’s story. While the Italian Foreign Office initially denied Butler and Mussolini met in 1926, it eventually conceded that they did, in fact, meet. The point of this story is that time, albeit a long time, eventually reveals the truth no matter whether an individual or a government tries to suppress it.

Protest against fascism, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia 2018

Espionage Down Under (Australia, 2018)

Quickly passed in 2018 under then Prime Minister Malcolm Trumball as a modern version of Australia’s Crimes Act (1914), the National Security Amendment (Espionage and Foreign Interference) Act of 2018 raised red flags with media companies, lawyers, journalists, and observant readers. Some of the issues were how speech can be interpreted in journalism.

“You are understanding the Chinese are China. We always say, ‘I’m Chinese,’ that does not mean I’m from mainland China ,” said Di Sanh ‘Sunny’ Duong who was brought in for questioning.”

Seeking to end the People’s Republic of China’s (PRC) interference or influence in Australian politics, the government’s first case was in March 2024, and he (Duong) was found guilty of preparing for, or planning, an act of foreign interference with a sentence of almost three years.

Mr. Duong is an ethnic Chinese born and raised in Vietnam. He moved to Australia in 1979, slowly building himself up as a self-made man, even taking a turn at politics by running for state election in 1996. After becoming a community leader, he mingled with mainland Chinese and Australian politicians.

All of his activities raised red flags, which culminated with his $25,000 (AUD) donation to a community hospital and the comments above that made him a possible pro-Chinese collaborator. Whether this was his intent or not, I cannot say, but it has raised concerns about xenophobia and whether Asian nationals can be labeled as possible traitors, but the problems continue from here.

In 2018, journalist Annika Smethurt of News Corp had her home raided because of the “alleged publishing of information classified as an official secret” that could undermine Australia’s national security. The classified information was a plan to allow the Australian government to spy on citizens’ e-mails, bank records, and text messages as part of the duties of a then unknown cyber task force—the Australian Signals Directorate (ASD).

A source familiar with cyber spying was quoted, “It would give the most powerful cyber spies the power to turn on their own citizens.”

Finally, in 2023, three anti-protest bills were passed in the provinces of New South Wales, Victoria, and Tasmania to allow stiff fines and jail time for protestors including unions. South Australian Council of Social Service CEO Ross Womersley summed up the situation best, “Protests, including peaceful disruptive protests, have been the key to achieving many of the welcome changes and improvements in our community and the rights that we all take for granted. Disturbances and interruptions are the things that invite and cause us all to stop and reconsider. Being punished unreasonably seems completely at odds with our democracy and the community we would like to continue to build.”

Bangladesh PM Sheikh Hasina wins controversial election | Al Jazeera Newsfeed 2024

President for Life? (Bangladesh 1996, 2009– )

In early January 2024, Sheikh Hasina, the Prime Minister of Bangladesh, won her fourth term with almost no opposition. Visit the website of her political party, the Awami League (AL), and you will immediately see a banner that proclaims that PM Hasina is “The Daughter of Democracy.” Yet reports stating that the lead-up to the election was marred by protests and scrutiny that saw opposition members from former Prime Minister Khaleda Zia’s Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) either pass away while detained by police or given long jail sentences and fined prior to the election. Zia is currently deathly ill and not allowed to leave the country for treatment. This is despite proclamations from the AL that it was an “open and inclusive” event that had the lowest voter turnout yet.

“Democracy is dead in Bangladesh,” stated Abdul Moyeen Khan, a member of the BNP, which is one of the main parties that opted to boycott the election for the second time.

Sticking with our main topic, how did Sheikh Hasina, a former exile, come to not only contend with the military regime of General H.M. Ershad (1982–1990) but to unite the then-fractured AL? My answer is that she used the tactics of a dictator while further moving the country away from a democracy, a task started by Ershad, and by tying the country’s success to her rise.

President Reagan Meeting with Lieutenant General H. M. Ershad of Bangladesh on October 25, 1983

How did Bangladesh get to this point? Looking at its growth is a strong indicator of the economic success during her terms. A rise in GDP from $71 billion (2006) to $460 billion (2022) came mostly from clothing and accessories, which made up 85% of exports as of 2021. Brands such as H&M, GAP, and Zara receive a wide variety of items from the various garment factories located throughout the country. This has also brought scrutiny and the occasion article about work environments and low pay.

Bangladesh GDP Growth Rate 1971 (Year of Independence) -2024

Education has also improved most remarkably for women as has gender parity. As the country improved, the authoritarian government also increased it power.

On the surface, this looks great, but underneath it has the following problems:

• The Rapid Action Battalion (RAB) is a death squad disguised as an anti-terrorist and crime unit within the Bangladesh police force. Trained by various countries, including the United States, the aftermath of 9/11 pushed the government to create a special task force to deal with new threats. Unfortunately, they have been used to punish nationals and commit extrajudicial killings.

• Rigging of elections has a long and unfortunate history in Bangladesh politics going back to its founding in 1971 and name change from East Pakistan. Elections are also known to be violent with protests, kidnappings, and jailings of dissident voices.

• The volatile political climate has led to one-party rule, which is an unfortunate reality that makes the claim of “democracy” a farce. I foresee a possible uprising similar to what PM Hasina and Khaleda Zia orchestrated to end the previous dictatorship, but then the question becomes can Bangladesh continue its rise without Sheikh Hasina at the wheel?

Tens of thousands protest in Chile: 'We've reached a crisis' 2019

Conclusion

For many Americans, the Patriot Act (2001) is a turning point in government overreach and security. For many other people, the worldwide protests from 2018 forward were when they felt that their governments overstepped their bounds and started keeping a watchful eye on their citizens.

What this article has hopefully highlighted is that “democratic” countries have a long history of keeping an eye on or deeming their own nationals as possible threats to security and government. Unfortunately, many more countries could be added to this list. For example, in Chile during the 2019 protests under former President Sebastián Piñera, the Carabineros de Chile (Police) fired at citizens as the country fell under martial law. Both Canada and Brazil’s freedom of speech laws are currently under attack by their individual leaders President Luiz Lula da Silva (Brazil) and Prime Minister Justin Trudeau (Canada). Fortunately, people in all of these countries have an option that people in other forms of government do not have: a voice.

It may sound a bit saccharine, but in each of the above cases, speaking out and protests are what brought these abuses to light and continue to remind us that, although we have many rights, the citizens speaking out against injustices are the ones who secure these rights.

Freedom of Speech protests in Brasil 2024