Fare Increases & Turnstile Politics (The Americas)

Can Major U.S. Transit Authorities Fix Themselves? (Opinion)

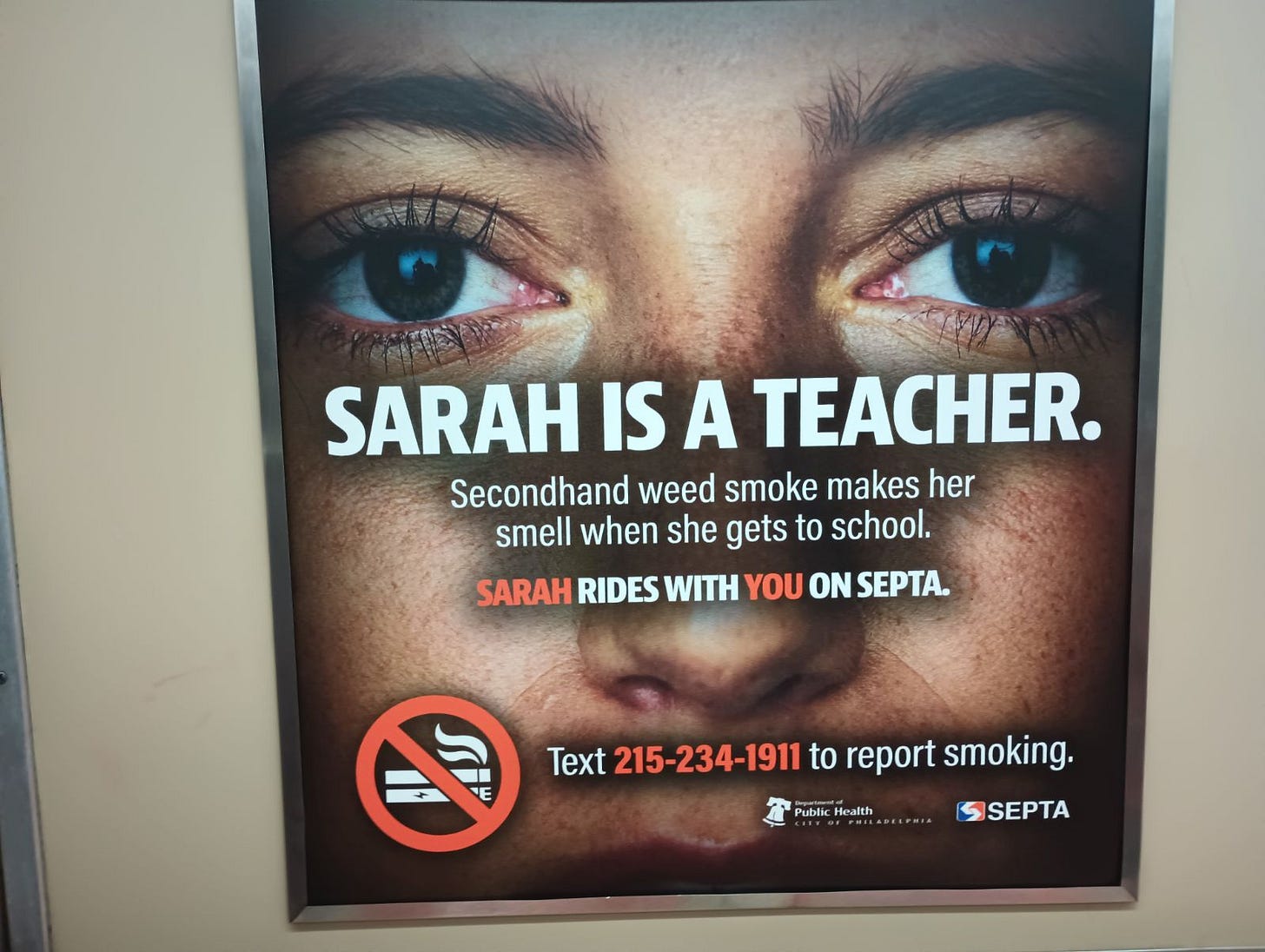

A normal sight for Night Owl (Bus) Riders in Philadelphia. (Credit: Thibert)

A successful Metro ticket transaction requires would-be passengers to swipe their cards above a sensor which is typically followed by an upbeat double chime. But when no fare option is available on a Metro card, or there is a technical error, people hear the game-show-like buzzer—quick and sharp. In most cases, it matters not, as it is an open secret that paying the $2 fare is not necessary for transit.

The passengers continue past the plastic cages installed to protect Philadelphia’s South Eastern Pennsylvania Transit Authority (SEPTA) drivers from any form of violence. Well, most forms of violence, as indicated by the number of drivers and passengers who are either injured or murdered while on the job.

The boarding process is repeated by the next person, while some forgo the charade and simply enter without ever acknowledging the fare or attempting to pay it at all.

This scene plays out each day, but at night, it happens in a different light. From 12:01 a.m. to 6:00 a.m., the Broad Street Line (BSL) and Market Frankford (EL) night-owl buses replace the trains, which effectively turns them into moving shelters. A few passengers are homeless, fentanyl addicts. While people with mental and addiction issues are easy to spot, the violent passengers make all of the other passengers wish that the driver had simply steered past them instead of allowing them passage.

Somewhere within this mix are the people who work late shifts and are in transit to work or to go home. They are easy to spot because they typically pay their fare.

Fares Increases

On November 24, 2024, the following long-expected and delayed notification was released to passengers: “SEPTA (South Eastern Pennsylvania Transit Authority) is planning to increase fares when Travel Wallet (fare storage) is used, effective December 1, 2024” Then the new fares are listed.

As a SEPTA driver told me, the new fares actually mean nothing because they do not affect the many passengers who evade fares. When I asked him why SEPTA did not do something, he freely echoed what many SEPTA workers have said: It’s not their money and SEPTA does not want them risking their lives.

Yet what the policy reveals is a flaw in logic. If transit agencies need to decrease lost revenue, why not improve the fare acquisition apparatus? Why let conditions deteriorate and push passengers away? This is why the recruitment of new transit police officers is declining.

For people living in Philadelphia and other major U.S. metropolises, it has been known for years that many transit agencies have been moving toward what is called the “transit fiscal cliff.” From Philadelphia and Washington, D.C., to Chicago, poor management and operation decisions have made transit companies reliant on an influx of last-minute funding from the states to continue operations. Oddly enough, this does not affect the raises given to many top officials in transit agencies.

On November 22, 2024, Pennsylvania Governor Josh Shapiro relocated $153 million from the federal highway capital funds to SEPTA. While in the Washington D.C., Maryland, and Virginia (DMV) areas, the Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority (WMATA) was offered “millions in aide to help close the transportation agency’s $750 million budget deficit” in February 2024. Meanwhile, the Chicago Transit Authority (CTA) was looking at a $577 million budget shortfall in 2026.

All three transit agencies have offered plans to drastically reduce services and keep operations going. Most of these plans will affect low-income workers, inner-city neighborhoods, and other people who depend on mass transit.

Although fares make up a small portion of revenue for transit agencies, each agency is suffering from fare evasion, ebbing ridership, crime, aging infrastructure and the lacking of police protection. All of these topics have been covered extensively, so here I want to focus on why faulty transit systems are allowed to remain faulty.

Gov. Josh Shapiro speaking at a press conference at the Frankford Transportation Center in Philadelphia on Friday, Nov. 22 about funding for SEPTA. (Capital-Star photo by John Cole)

The Power of Social Media (United States)

During the latter half of the 2010s, a SEPTA passenger posted images on social media of one of the track’s areas. Normally filled with trash, it is a site that Philadelphians have learned to accept while riding mass transit. With her photos, she included how revolting the track area was and how SEPTA should take care of the matter. Although SEPTA employs porters and power-washing teams to clean various stations, they typically do just enough. This is best described by what a porter once said to me, “If it smells clean, it is clean.”

This case was different as her small protest embarrassed SEPTA and prompted management to send workers to the track area and clear it of trash. This highlights another issue that disappeared when dealing with transit agencies: they lack the urgency to improve mass transit.

So how were similar matters dealt with during the latter half of the 19th century? During this period in the United States, the law for dealing with Black passengers was that they sat in either a colored section, if seats were available in a Jim Crow car, or waited for a colored transit car.

An example of this discrimination is the exchange between Black Civil War hero Captain Robert Smalls and a White streetcar conductor. During the war, Captain Smalls pilfered a Confederate steamer named The Planter from a Charleston, South Carolina, wharf and sailed it along with his family and runaway slaves to join the Union Navy.

Then in early 1865, Smalls entered a Philadelphia streetcar and was quickly asked to leave by the conductor. Smalls asked, “Is this the law?” The conductor stated that it was, and in reply, Smalls stated “Then, I’ll obey the law.” The law of the land, during this period, was determined by the 1857 Dred Scott decision that refused citizenship to anyone of African ancestry.

At this moment, a White passenger revealed Small’s identity, and the conductor replied, “Company regulations.” Then he showed his ignorance by saying, “We don’t allow Niggers to ride!” This was the term that Black Philadelphians became uncomfortably accustomed to hearing.

By the early 1860s, the city operated 19 streetcars pulled by horses along tracks that crisscrossed the city. Each streetcar had a conductor and a driver. By the late 1860s, they were slowly allowing in colored passengers due to changes in the law brought about by protests of the first generation of Civil Rights’ leaders such as Octavius V. Catto, Carrie Le Count, Lucretia Mott, Miller McKim, Harriet Purvis, and Benjamin P. Hunt who wrote the book, Why Colored People in Philadelphia Are Excluded from the Street Cars.

Hunt wrote, “We are opposed to the exclusion of respectable persons from our passenger railroad cars on the grounds of complexion.” He continues, “We have heard with shame and sorrow, the statement that decent women of color have been forced to walk long distances or accept a standing position in the front platform of these cars, exposed to the inclemency of the weather.” He concludes with a resolution to end this situation and form a committee to oversee and hand deliver new demands to each president of the main mass transit companies in Philadelphia.

Through these actions and continuous protests, on Friday, March 22, 1867, then Pennsylvania Governor John W. Geary signed into law a bill requiring the fair treatment of Black passengers on streetcars. This event was echoed in many cities, including San Francisco, Charleston, and New Orleans, which passed their own bills at that time.

Somewhere between then and now, the urgency to not only say something but become willing to protest about mass transit in the United States was lost. Many will say this silence is due to the busy lives of passengers and state that it is hard for anyone to complain who depends on mass transit regardless of its deficiencies. Others will point out the many town-hall-style meetings that are scheduled and promoted on social media. Yet, despite these meetings, mass transit continues to decline due to bad spending habits and errant public relations stunts. The option that mass transit workers take—an organized strike—often gets the desired results.

Streetcar utilized in Philadelphia, circa 1865 (credit Library Company of Philadelphia)

Daily Operations

As of late 2024, multiple SEPTA departments that cover bus and train lines in Philadelphia County and surrounding areas have moved closer to a strike. Each where delayed due to tentative agreements. The main issue is safety. This same issue extends to passengers, but they are treated differently. In the case of the drivers, they have unions, whereas the passengers are often made promises of increased safety that quickly disappear when the media is pointed elsewhere.

According to septa.org, “SEPTA had a 34% decrease in serious crimes in the system during the first three quarters of 2024.” This decrease is credited by outgoing SEPTA CEO and General Manager Leslie S. Richards to the impact of the SEPTA Transit Police. The inside joke is that the SEPTA Transit Police are never to be found, the call system to alert dispatch is dodgy, and overall SEPTA has never felt more unsafe. Many passengers don’t report crimes or feel that nothing will come of it.

In Chicago, the situation is a bit more unsettling with an increase in crime due to the decrease in passengers. This situation has ultimately led to triple the number of violent crimes since 2015.

The WMATA stands out in this regard. You see attendants on the platform and the Metro Transit Police Department (MTPD) officers are present enough to give passengers a sense of security. To get a different perspective, I interviewed one of the veteran booth attendants on SEPTA. One of the first statements made by my interviewee, who asked to remain anonymous, and various workers was that they were only a few years away from retirement.

Booth Attendant: If you have somebody who is not holding them accountable when they give them a fine for infractions on the transit line, they will keep doing the same thing. So, I say the biggest problem is fare evasion. My thing is that sometimes social media has to get a little more involved because a lot of people don’t know that SEPTA is raising the fare for people who pay their fare. I don’t think that is fair. SEPTA needs to cut down on the fare evaders.

Thibert: How much does SEPTA rely on these fares? Why are they allowing people to fare evade and does everyone know that this evasion is allowed?

Booth Attendant: They aren’t allowed to evade fares, but they (passengers) don’t get caught.

Thibert: I heard that staff members were told to let them go. If they are doing it, just let them go.

Booth Attendant: We can’t do anything because we’re not the cops. At one time, fare evasion was not as bad as right now.

As we talk, we notice a passenger pull back the turnstile to slide pass and enter the Metro station signaling a buzzer that ends after a few seconds.

Booth Attendant: When the fare evasion wasn’t so bad, we were told to call the cops and they would meet the evaders on the train. Now there are fewer cops. It’s hard to call the cops to catch the evaders. That is where the problem is. It’s not our job to keep evaders accountable.

Another buzzing sound goes off and alerts us to another fare evader.

Thibert: Evading happens so often that it appears that only the foolish passengers pay. I see evaders on the bus as well like the elderly and Temple University students. It feels like practically everyone is doing it (fare evading).

Booth Attendant: My thing is with the accountability. To me, fare evading is stealing. If you think this is okay and that in life it is okay to do this, somewhere in life it will catch up with you. That is what fare evaders don’t see. There are repercussions to whatever you do.

Thibert: When fares change up or down, they still will not pay. This sends a message that evaders will always evade punishment.

Booth Attendant: That’s in your head. They will never escape because they may always be broke or someone may be stealing from them. All they see is everybody else doing it, so they think, I’m going to do it, too.

Thibert: Let’s talk about another topic: smoking on the train.

Booth Attendant: That’s another important topic!

Thibert: Has it become normal to see people smoking or shooting up?

Booth Attendant: On Saturday, I tried to come down the stairs to the booth. But I couldn’t because there were 20 addicts laying all over the steps—everywhere. I had to call dispatch to let them know that I could not get through because there were not any police officers and the elevator was broken. I had to ask a coworker to come upstairs, step over the needles and the people, and let me in.

Thibert: I see the same throughout “Shitty” (City) Hall, especially at the top of Staircase #1, which has become a place for addicts to rest and shoot up.

Booth Attendant: Yet they have more rights than we do.

Thibert: Is there anything that people like myself and other SEPTA riders can do to improve matters? Would protests like in the 1960s–1970s change things?

Booth Attendant: You can give it a try.

Thibert: You don’t sound sold on my idea.

Booth Attendant: Your voice needs to be heard. For us, though, there are a lot of things that we can’t go to social media about because we are under SEPTA. But I am frustrated with going to work every day, dealing with the crackheads and their needles, and confronting the homeless. Now add on the fare evaders—I’m done. I’m drained because the system is down.

Thibert: Do you think the higher-ups care about these things?

Booth Attendant: No! If they cared, they would have hired more police officers—that’s what I feel. I don’t know what’s going to happen. I just pray that I make it.

I say make up your signs. Go to 1234. (SEPTA headquarters address)

Thibert: Would SEPTA care if people protested?

Booth Attendant: They don’t care because they are already funded.

Thibert: They will get their funding regardless of protests? So, why care?

Booth Attendant: They pump up the public with, “Oh, if we don’t get the money, we will move up the rate.” That’s just to make it seem that SEPTA is poor. Where is the money? It is not going to the workers! They are trying to give us 3.0% more, which is really 1.5% because they want us to pay more into our benefits. They are not giving us anything. In the meantime, the cost of living is going up…I don’t know.

Thibert: This sounds like a horrible cycle of pushing the blame elsewhere.

Booth Attendant: Mayor Cherelle Parker says she is cleaning up the Kensington neighborhood, but while she is doing that, she is pushing people down here. So how can you say that people don’t get the big picture?

I don’t know what the solution will be?

Thibert: I understand that a lot of people work and can not stop to protest because of their reliance on SEPTA, but by June 2025, if they cut service as part of cost savings, people will feel it, so we are moving toward that now or in a year.

Booth Attendant: That’s another thing. They cut the schedules but cannot hire enough drivers. They make it seem as though the problem is a lack of funds. That is not why. They are cutting service because people who apply can’t pass the drug test. The younger generation wants to come in and have weekends off. SEPTA just can’t hire enough people or get them to stay.

A group of teens smoking and drinking on SEPTA mass Transit. (Credit: Thibert)

Movimento Passe Livre (Brasil)

Described as a group of “ordinary people who have come together for almost a decade,” the Movimento Passe Livre (Free Pass Movement) has been working toward eliminating metro fares throughout the country. These types of groups and initiatives can also be found throughout the United States.

This group merits mentioning because of its origin and how it evolved from public protests. Starting as the Zero Fare Project by then Secretary of Transportation Lucio Gregori in the early 1990s, the project was abandoned until the early 2000s. At that time, two events happened: Bus Revolts of Salvador de Bahia (2003) against a fare increase of 1.30 to 1.50 reals and the Catracas Revolts in Florianopolis (2004–2005).

In both events, students refused to pay the fare increases. Protests in Salvador followed and gained public support when reports of police abuse were leaked. Three weeks of unorganized and random student protests blocked streets and caused traffic jams but did not stop the fare increases. However, they did halt the hikes for a year and extended half-fare options. This event also laid down the groundwork for future protests.

The Florianopolis Revolts brought about the closure of two main bridges, and this cut off access to the island, due to large numbers of protestors. According to Elaine Tavares, a journalist, “Mobilization by the island’s population against the increase in urban bus fares showed that for those who run the city, the only rights guaranteed in the city are those of the owners of transportation companies and terminals, which are private. In the name of what they call order, the military threw bombs, fired rubber bullets, drove horses at the people, and incited violence and riots.”

Nicknamed the Turnstile or Catraca Revolt, the protests lead to Florianopolis City Hall where a standoff took place that was met with violence and forced the protestors to flee. Yet it was what has been titled the Twenty Cent Revolt (2013) that happened throughout numerous cities and brought to light how the increases revealed concerns about inequality, greed, and injustice.

Over the two-week-long revolt lead by Movimento (MPL) a 20 cent hike from 3.00 to 3.20 reales brought out protestors in nine different cities with numbers ranging from 5,000 to 200,000 of mostly youth affected by the “high cost of low-quality services.” Protests increased as then President Dilma Rousseff was booed in public as construction and funding for the World Cup 2014 took precedence over people who could not afford to attend the matches or take mass transit.

The publication Folha de São Paulo and Upsidedownworld.org broke down the existing fares stating, “Public transportation in cities like São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro is among the most expensive in the world and the quality is terrible.” While a resident of Rio needs to work 13 minutes for a fare and a resident of São Paulo 14, in Buenos Aires one needs to work only a minute and half, 10 times less. In cities such as Paris, New York, and Madrid six minutes and in London 11 minutes.

My own experience riding Metro Rio in Rio de Janeiro highlighted the poor, crowded conditions that mixed with humidity and late trains forced passengers to yell, chant, and scream until the train arrived, creating a vacuum that absorbed most of the waiting crowd.

Overall, these events became the backbone of MPL’s continued protests, but political scientist Jorge Almeida stated that toward the start of the World Cup 2014 “The prices went sky high with mega events, affecting in particular the poorest who suffered from the inflation of 11% to 12%.”

The protests would go on to become the inspiration of Mexico City’s “Movimiento Pos Me Salto” (2014) which was in reaction to a fare increase of 66% to 5 pesos. Similar to Brasil’s poor infrastructure, no clarity, and the revelation that many Chilangos (people from Mexico City) live check to check, prompted students to force open the turnstiles and allow passengers to ride for free.

Police fire rubber bullets at demonstrators protesting a price increase for public transportation in Sao Paulo, Brazil, Thursday, June 13, 2013. (Credit AP Photo/Nelson Antoine)

Estacion Santa Lucia (Santiago de Chile)

I remember receiving a photo of the Santa Lucia Station in Santiago de Chile’s red line. It was not my favorite station, but it was a familiar start and end point. It was hard to recognize it with the gates closed and the debris around it. That was in October 2019 when the country experienced the biggest mass protests it had ever experienced. The spark was an increase in fares, which highlighted other social and economic issues. Over the next few months, I watched from afar, wishing that I was there. I left in September, only a few weeks prior to the start of the riots.

The reports came in that the police shot at civilians immediately drew comparisons to Pinochet’s dictatorship. Knowing Santiago, you become sometimes annoyed but accustomed to the student protests culture, but I never quite understood it. While working on this story, I asked myself how did the country develop this culture? To get an answer, I reached out to a student protestor, who witnessed the events of the protest. They have asked for their name to be omitted.

Translated from Spanish

“I think there must be some historical background in Latin America that has been transmitted during various periods about strikes and protests as a means of action against situations that harm society, especially the lower and middle classes.

“At school, I learned a lot about the history of Chile, and after colonization, there were protests and strikes. These occurred especially during the wars in the north (the Pacific War and others in that period). Before and during the dictatorship, there were strikes and protests, despite the military oppression that existed in the country. The protests and strikes of the wars of centuries ago and those of the dictatorship ended fatally.

“The reason why protests and strikes exist and continue to exist today is something I cannot explain in a concrete way, since I believe that it is part of the Chilean and Latin American culture to demand justice or something similar when it affects you or a sector to which you belong or are familiar with. I believe that protests and strikes also have a greater magnitude, because when these demonstrations occurred, they affected large social groups such as the lower and middle classes.

“Protests and strikes may also have a greater magnitude here, since in Chile our population is much smaller than that of the United States, and the vast majority of injustices occur in the capital, which is where most of the country is concentrated. Chile is a very centralized country, speaking territorially.”

Chilean students refusing to pay the increased fare hike by jumping the turnstiles. (Credit People’s Dispatch)

Conclusion

Somewhere between the 1960s–1970s Civil Rights era and today, the United States moved away from protesting for better service on public transportation. Today, when you hear of a protest, it is likely related to the worker unions’ demands.

I strongly believe that metro companies such as SEPTA, CTA, and WBMTA capitalize on the lack of pressure to make improvements. Honestly, why should they? From their perspective, there is no urgency to hire better police, reinforce laws, stop fare evasion, and offer a safe clean ride. Instead, they provide bonuses to management, who after a few years, move on to greener pastures.

Latin Americans have a different approach, parts of which can be implemented in the United States. That may involve being more active, but as a SEPTA passenger once yelled at me after I advised her to bring a complaint to SEPTA, “I’d rather yell and complain to you because I don’t have the time to go to them.” I guess with that attitude, we should all just get used to smelling weed on the trains.

Great discussion. I see this issue even more broadly with people being more individual focused rather than on group action regarding local issues ("I don't need to worry about transit, because I'll just Uber")

Another example (that irks me as a New Yorker) is general enforcement of car infractions. Whether red lights, speeding, hidden plates, double parking, bike lane parking etc, there lately feels to be no enforcement at all, which only further promotes this type of behavior (and we can see the effects of it with higher car insurance premiums). This is also an example of individual focus over group action.