Compromises

To Regress, Move Forward, or Rectify

1877 Electoral Commission

When I apply for a job and see many white faces in the room, I wonder if I am being hired based on my skills or to meet a color quota. I do not want to be a diversity hire or be called BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and People of Color).

At the other end of the spectrum, I put my head down in frustration when someone black is mining for something to call racist. My attitude has grown ambivalent as among black society, I am a misfit. I feel that others have treated me as an outcast, but now I accept that status. Even while dating a black woman, I was asked, “You want to be one of them, don’t you,” meaning that I secretly wished to be white.

I have sat and watched what goes on around me without animosity or anger, just pessimism. My time is filled with observations as I sit on my porch and watch passersby in my all-black neighborhood. I revel in my blackness that, according to some, I apparently want to trade in for a lighter shade.

A thought passes through my mind, Why haven’t we already moved past this? Realistically, given that the black peoples were first involved in politics in the late 19th and 20th centuries, then we should be farther along than we are. My thoughts shift towards those moments when things could have been done differently and to the compromises made to at least get us to this point in time.

In mid 2019, the 1619 Project was published by the New York times. Referring to the year when the first slave ship arrived in British North American as “America’s original sin”. A subsequent book was released and upon it’s arrival numerous press releases and book reviews. I remember the white “ally” telling me that the book was a must read and advising that it was my duty to read it.

A copy, given to me, still sits on my mantal. I will get to it one day. The topic is not the most pressing for me. That period is not of high importance at the moment.

This may get me sacrificed as a type of race trader. Believe me, I am not. Yet there are events that do not move me, despite getting lots of press coverage:

• The Founding Fathers attitude toward the preservation of slavery does not bring me to a boil.

• I am not mad about slavery. Someone’s ancestors once owning slaves does not incite a reaction by me.

• What has always bothered me is compromise.

Everything before the end of the American Civil War (May 9, 1865) were the actions of impetuous, stubborn men and women with moments of genius and the promise of something more. What happened after that makes me feel a sense of loss time, regression, and disappointment.

When I look at the histories of other countries, my mind is also drawn to those similar moments in their specific histories.

Where would race relations be if the moments we are experiencing now had already transpired? Those we call the first to make an achievement could have been simply the eighth or 30th in that position. The first black, Asian, indigenous, and so forth would simply be another American who achieved an accomplishment. I keep restating, “what if?”

Compromise is a fact of life. We learn this action to better navigate adulthood. We cannot always have it our way, so by compromising, we can accept and build on what we can get out of an agreement.

Yet what happens when a country decides to compromise for whatever reason? In the case of the United States, I could simply say “racism” and call it a day. Yet there is always more.

That is the theme I want to focus on: compromise and how it not only molds a country, but also how it can either retard, stagnate, or assist in its moving forward.

Five Compromises Causing Regression - United States of America

Nineteenth-century America experienced five compromises that led to today’s cultural and political situations. In these initial compromises, the ignored issue of slavery, or that “peculiar institution,” was at their roots.

The Missouri Compromises in 1820-21 (first compromise) allowed Maine to enter the Union as a non-slave state, Missouri to enter as a slave state, and banned slavery in lands north of Missouri’s southern border. The issue would continue with The Compromise of 1850 (second compromise) focused on the lands added after the Mexican–American War and included California, Utah, and New Mexico. The Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 (third compromise) centered on the inevitable inclusion of Kansas, Nebraska, Montana, and the Dakotas.

The Dred-Scott case (fourth compromise) overruled the Missouri Compromise, by stating that it was unconstitutional. This decision was one of the bigger sparks igniting the American Civil War.

When the Civil War ended, Reconstruction began. Coined as the Second American Revolution, Reconstruction was precisely what its name states: a hard re-set spurred by the Emancipation Proclamation, the end of the Civil War, and the 13th to 15th Amendments.

Reconstruction officially ended partly due to the Compromise of 1877 (fifth compromise). Similar to today, election results in the 1876 presidential election between Republican Rutherford B. Hayes and Democrat Samuel Tilden were contested. Tilden won the popular vote by 250,000 as well as 184 of the 185 electoral college votes needed to win the election. Unfortunately, Republicans refused to concede, leading to a drawn-out dispute between both political parties. Violent clashes included African Americans being attacked and blamed for the swing in votes.

Parties begin pointing fingers at each other claiming electoral fraud. The outcome of the election rested on disputed returns from Florida, Louisiana, and South Carolina. Congress decided to move forward in creating an electoral commission to come up with a resolution.

In February 1877, Democrats agreed to accept Hayes as the victor and to uphold all rights of African Americans in exchange for the reinstatement of home rule and the withdrawal of federal troops from the South. Additional concessions included the addition of a Southern delegate on Hayes’s cabinet and aid to railroad magistrates to extend various train lines.

President Rutherford B. Hayes was elected and then referred to as “His Fraudulency,” as all of his promises could not be kept. Reconstruction ended. Individual states made laws to disenfranchise Black and Brown Americans, Black Codes, Jim Crow, sharecropping, and violence just increased segregation.

Worse, this was only the beginning of segregation economically and politically. Throughout the next few presidencies, the gains made during the terms of Lincoln through Grant decreased.

Specifically, from presidents Chester A. Arthur to Woodrow Wilson (excluding James A. Garfield’s very short term), a number of rollbacks occurred.

In the United States vs. Reese, the Supreme Court ruled that the 15th Amendment was limited to preventing discrimination in the right to vote on account of race, color, or servitude.

Since Sections 3 and 4 of this amendment were not confined to a limited form of discrimination, they were deemed unconstitutional. The law was repealed in 1894. That year, the Civil Rights Enforcement Act (1870) was also deemed unconstitutional.

Specifically, Section 6 forbids the follow: “to injure, oppress, threaten, or intimidate any citizen, with the intent to prevent or hinder his free exercise and enjoyment of any right or privilege granted or secured to him by the Constitution or laws of the United States.”

The United States vs. Stanley (known as a civil rights case in 1883) disarmed the Civil Rights Act of 1875, allowing private businesses to discriminate in both hiring and business practices. The specific cases ranged from denial of hotel accommodations, employment at the New York Grand Opera, and seating in a passenger car on a train. The ruling opened the door to Jim Crow laws.

The Cruikshank Case (1876) involved a white mob killing 100 black nationals in the Colfax Massacre in Louisiana due to an argument about a gubernatorial election. The Supreme Court decision cited that the 14th Amendment did not protect individuals against the actions of other individuals but only from the actions of the State, which resulted in the dismissal of the case.

Events such as the Wilmington, NC, Massacre (1898) and the removal of black politicians from D.C. politics led to a loss of governmental representation not seen again until the 1960s.

Compromise to Move Forward - Nicaragua

Nicaragua has been in competition with Panama since the late 19th century. During that time, both countries fought for a national identity and economic power in efforts to establish their strategic roles within Central America.

For Panama, this goal was achieved via two actions: 1) its annexation of the canal from Colombia, which was formalized on November 3, 1903, and 2) the United States’s role in completing the canal project left behind by France. Nicaragua’s goal of creating its own canal was never achieved, leaving it with a minor role within the region.

Surveys done in 1901 established that Panama had the best overall conditions to make the canal project a success. This never deterred the government of Nicaragua from attempting to make it happen regardless of environmental and population issues. Construction of the Nicaraguan Canal would take a back seat throughout the 20th century.

In the early 21st century, Iran courted the Nicaraguan government as part of its overall goal to create footholds within the Americas. An Iranian embassy was opened within the capital, but no progress was made on renewing interest in the canal. Private investments from Beijing-based businessmen Wang Jing, president of HKND Group, reactivated the plans.

Despite promises of full transparency and the fair value of the land, distrust among residents and farmers increased when soldiers and police accompanied HKND surveyors to measure the land. This quickly sparked protests by residents who lived along the work path stretching from Punta Gorda (East Coast) to Brito (West Coast) of Nicaragua.

Citing distrust and unfair business practices, the residents and farmers were met with violence during a protest along the Managua-San Carlos Highway. Nicaraguan police under President Daniel Ortega were met by threats to burn a gas tanker and block off towns if attempts were made to displace citizens from their homes.

In the end, HKND moved on from the project, citing that Nicaragua was a minor player in Latin American affairs. This withdrawal coincided with the ongoing Nicaraguan protests that revolved around other matters concerning the government.

In early 2022, President Ortega invoked excitement over China’s Belt and Road Initiative possibly coming to Nicaragua. Although a canal is an infrastructure project, it is not a stretch to believe that investment in the long-term dream of a canal is on the agenda. For its part, Russia has also showed interest in the project, which raised U.S. concerns about Russia’s inroads into the Americas.

In this case, the goal of moving forward has created Nicaragua’s version of Manifest Destiny, or better yet, Economic Destiny, that continues to drive political and government decisions. My question then becomes: What if Nicaragua had decided to take another route after construction began on the U.S.-Panama Canal?

Nicaragua is the only Central American country with both Spanish and British influences after having been a shared colony of both. The country has also experienced multiple dictatorships, leading to both an import-driven economy and a government dependent on other countries. Most of the country is agrarian land. Seventy percent of the population works in farming either cotton or coffee, leaving only thirty percent for food.

The goal of building a Nicaraguan canal will only lead to more poverty and environmental disasters. Is this dream worth the hunger-fueled nightmare that its nationals currently live in?

Compromise to Rectify - India-Bangladesh

According to a legend from the early 18th century, a chess match between the Maharaja (great ruler or king) of Cooch Behar in West Bengal and a Mughal commander led to a wager of lands in their possession. The true story of what was once the worlds largest number of enclaves is far different from the legend.

As the Mughal state expanded into Northern Bengal (late 17th century), they were initially unable to occupy lands within the Kingdom of Cooch Behar. Powerful lords who owned land entrenched near the Mughals held out by forging alliances with the Mughals, which kept them in the kingdom. Over time, the Mughals made a few gains, and these small plots of land came to be called chhit mohol, meaning “enclave” in Bengali, and each territory paid taxes to their corresponding empire or kingdom.

As the Mughal state dissolved, the governor of Bengal became the ruler of these lands. Eventually, the governor was replaced by the British East India Company, who during the late 18th century, made all of these the enclaves a part of Bengal. The Maharaja was kept as a regional adjunct.

Throughout the 20th century, the condition of these enclaves led to confusion, stress, and a state of limbo after the following events: partition of Bengal (1905), partition (1947) forming Modern India and East Pakistan, and creation of Bangladesh (1971).

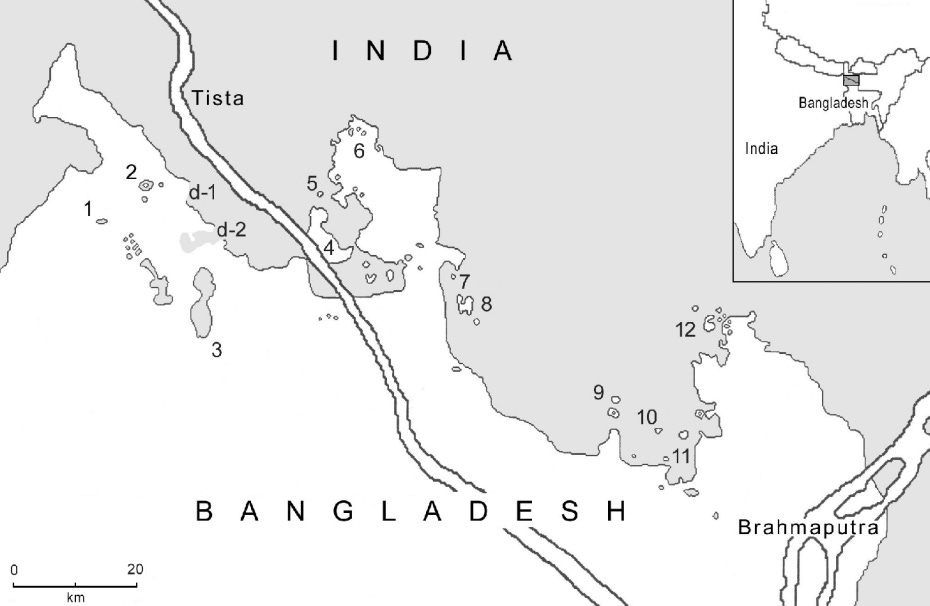

A total of 123 Indian enclaves survived surrounded by Bangladesh. Seventy-four Bangladeshi enclaves were in India. All of these enclaves existed along the northern border of Bangladesh in a zig-zag pattern.

Strained relations did not make the tension between neighboring countries better. Even the assistance by India in separating East Pakistan from Pakistan during the 1971 war did not improve matters in any sensational way. No real border between the countries was ever clearly established. The most that was done was the placement of a series of stone pillars that were put in place in 1934.

Although local authorities (Ansars) allowed freedom of movement outside of the enclaves, attempts to take hold of the lands never came to fruition.

In 1950, a procedure was put in place to allow traveling outside of enclaves. The procedure consisted having an ID card (that, in itself, a feat if the place the traveler had to go to get ID was in another enclave or in the main part of the country) and a formal announcement via telegram 15 days in advance of any trip. Finally, travelers were escorted to and from foreign soil.

The economic needs of those within the enclaves were often ignored in favor of the politics of their respective countries. People within these enclaves were harassed and treated as foreigners. Politicians found the issue too difficult to navigate and simply ignored it. Over time, the people living within these enclaves disappeared due to the inability of the governments to provide census records with accurate counts.

Now in a state of lawlessness, procuring legal paperwork, or any type of official documents, meant breaking the law. This left travelers at the mercy of police officers in both countries and libel to the penalized by both.

In some cases, a sub-enclave existed. An example is Haluapara, which housed citizens of Bangladesh but was surrounded by an Indian enclave in Bangladesh.

Over time, some enclaves ceased communications with their home country. Instead, they opted to self-govern. Eventually, the discussion on how to unravel the enclaves became an ignored topic. Some moved unsuccessfully towards establishing their own state.

The issue of religious affiliation added a level of complexity. Political parties used another faith system as a rallying point to incite violence, as in the case of the Indian National Congress Party forcibly removing Muslim inhabitants within the enclave of Shibproshad Mustafi by robbing and assaulting them. This sent fear through other enclaves that housed a majority Muslim population.

One day, a poster was found within one of the enclaves stating, “Muslims! The day has come to sell your blood to the Hindus. Hindus! Get your money ready”

On this occasion, Muslims from Dhabalshuti Chhit Mirgipur had to flee to another enclave to escape a mob of Hindus. Over time, the level of stateless that the various enclaves experienced became their identity.

They were vulnerable to outside forces when in May 2000 a mob attacked the enclave of South Moshaldanga, a Bangladeshi enclave in India. Homes were burned and people taken away. Yet what recourse did the residents have when they did not have access to emergency services or assistance?

The decades of disparity led to protests and mass walkouts of enclaves towards their respective host country’s capital to protest. Gang rapes, kidnappings, theft, and social limbo had taken their toll, which increased tensions between India and Bangladeshi. These protests would lead to an easing of passage outside of enclaves but was not a real solution. One would eventually come almost two decades later.

At midnight on Friday, December 10, 2021, and into Saturday, December 11, 2021, nearly 14,000 Muslims living in Bangladeshi became Indians and those living on the Bangladesh side became Bangladeshi. Those not in favor of the deal were allowed to leave for their country of choice. Almost 70 years after the partition, the enclaves officially came to an end.

Conclusion

Reconstruction-era United States had the birth pangs of a new country. Although my focus has been on the late 19th century there are a number of circumstances that ring eerily similar to events unfolding today.

I feel a sense of disappointment that this period is still widely unknown, even though it is a root cause of a lot of today’s issues. Take a moment to imagine what the nation would be if today’s circumstances had happened over 100 years ago? Where would we be now? What if Samuel Tilden had become the President?

Would Critical Race Theory be an issue? A silly name for a topic that is not a theory but historical facts. Would the Great Migration have happened? How would relationships with Hispanics, Asians, and other groups be affected by this change? Obviously, we have had road bumps, but at the rate African Americans were pulled towards political offices, generating wealth, and taking in education like sponges, how would the current generation have fared under their guiding hands?

Nicaragua may seem like an odd country to compare to the U.S., but I see similarities. Although to the detriment of its people and land, Nicaragua pushes forward on a plan to seek economic prominence and, instead, it sinks further. Why? It’s pursuing an outdated idea that does not reflect the needs and demands of the people now living within its borders.

Lastly, India and Bangladesh found ways to help their displaced peoples, but in the States, Indigenous peoples are still in limbo. A true goal, in my opinion, is to move away from making them feel as though they are not citizens and granting them full rights. I have always wondered if the issue was really land or not having their identity recognized and needs satiated.

In all of these countries, compromises were made that affected each host country. That is why I have always enjoyed learning about various histories as I hope do better. But if we continue to repeat errors and, in some cases, double down on them, what then?

I do not have solutions, simply observations that I hope someone in a century is not making about us today. Hopefully, we are not currently living in a sixth compromise.

Fin.

Pillar marking the boundary between India and the Bangladeshi enclave of Nolgram. The villagers are standing on a road in Indian territory, looking towards the photographer who is standing on Bangladeshi soil.

Proposed cut site for the Nicaragua Canal.

Negro Voting, Ballot Box, 1867 Georgetown Election, Black Americana

India - Bangladesh enclaves

Pacific Coast of Nicaragua