A Deeper Dive. A Conversation with Former President Donald Ramotar (Guyana)

Party Politics, Race Propaganda, and Foreign Influence

New Year’s address to the nation by President Donald Ramotar, 2015

Help me reach 1,000 subscribers by December 31st, 2025. Please share Emancipatory Research with anyone who enjoys reading, learning and conversing about history and geopolitics.

While conducting research and interviews in Georgetown, Guyana, I met with Donald Rabindranauth Ramotar, a former president (2011–2015) and a long-time member of the People’s Progressive Party (PPP). I was eager to hear his thoughts about two other former presidents, Cheddi Jagan and Janet Jagan, as well as his opinions on race relations, especially in politics.

Although I want to abstain from writing a biography, a short overview of Ramotar is needed along with my personal impressions of him. According to Freddie Mission of Kaieteur News Online,

“I believe he is still one of the less arrogant persons in politics (he is not arrogant at all) and one of the PPP leaders not infatuated with the company or the rich as Bharrat Jagdeo is.”

“Ramotar as a political animal is another kettle of fish. He is not a politician with leadership qualities. He never had such abilities. He never made himself a name in politics. He started out his political career as a counter-clerk in the PPP business company, GIMPEX, in Regent Street. Then he graduated into GAWU leadership”

(Mission, Freddie. “Donald Ramotar: A Short Biography,” Kaieteur News Online, 5/07/2013).

Commander-in-Chief President Donald Ramotar inspects the Guard of Honour at Eve Leary prior to the opening ceremony of the Police Officers’ Annual Conference, 2015 (Credit Guyana Chronicle)

The Interview

My immediate impressions of him were that he was a kindly grandfather and a voracious writer. He wrote for Janet Jagan’s PPP newspaper The Mirror and published a number of articles in that role. Like the Freddie Mission quote states, nothing about him seems presidential; instead, he is very grounded. Thus, the atmosphere and tone of our conversations were also very relaxed.

Thibert: Why is race still an issue in Guyanese politics?

Ramotar: I am of the view personally, and I must tell you in advance, that I am in the minority company of this view that I have. One of the things that I believe is that the electoral system that we have, the Proportional Representation (PR) that was imposed on us in the 1964, if you look at countries that have PR system, these countries most of the time have coalition governments and weak governments.

A coalition government encourages organizing people on the basis of race or religion and not on national issues. The constituency system actually encourages political parties. The PR system allows them to have many political parties. Wherever you find PR around the world, you will have these political parties contesting elections. You had Italy whose government changed twice or three times a year sometimes. It is also now said by some political scientists that it was the PR system that gave rise to Hitler in Germany. In South Africa right now, even though they have a PR system with some modifications, it’s fundamentally PR.

You can see that the People’s National Congress (PNC) united the people before they got into government, but shortly thereafter, although the PNC was a strong political party winning 66% of the vote, by now they have lost a lot of their positions and the majority of the votes in the country. This is largely because of the divisions PR tends to try to create within a society, and now seems to be emerging as a different racial problem in South Africa similar to our Indians and Blacks in our society.

In 1962, when Trinidad was going toward independence, there was a proposal for PR and the British opposed it on the grounds that it would create a weak government. Eric Williams, the first prime minister of Trindad and Tobago, also opposed it. He said, “You will vulcanize Trinidad and Tobago and make the problem of integration of the races even more difficult.”

Thibert: It is funny that you bring this up. I was going to quote from a book titled, Electoral System Reform for a Diverse Nation: The Case of Guyana. The author, a gentleman by name of Desmond Thomas, states the same thing, “Changing your electoral system would change race relations.”

Ramotar: I think so, because if you look at our system, we never had a racial problem. Race was never really a big problem in our society before Dr. (Cheddi) Jagan came back in 1947. There was not total and universal suffrage, but there was a great relaxation of the conditions that allowed working people to get involved in the voting for the first time. Jagan had overwhelming support from both Black and Indian communities in 1947. In 1953, the PPP won the election with the support from both Black and Indian communities. The problems began when the parties split in 1955 and the British encouraged (Forbes) Burnham to do that and he started the PNC with racism.

Before the PPP came into existence, there were two racial organizations. One was called the League of Colored People, which organized Black people, and the other one was called British Guinea East Indian Association. They were both middle-class, professional-type organizations competing for some of the crumbs on the political table. They never made a big impact on society among the masses of people.

We had a lot of harmony in our society. Many people who studied in Guyana are writers who I don’t agree with. They say the racial problem in Guyana began when East Indians came back after the abolition of slavery. They worked for less money than the former Black slaves and that created an antagonism. I don’t think that this is true because if you look at the (evidence), we never had clashes between Indians and Blacks from 1838–1962. After 1962 was the first time we had any clashes. Also look at the question of the Indians’ undercutting (the Blacks) and at how many (Blacks) escaped before they (the estates) closed down during that period of time.

All of this means (racism) was not necessarily true. Sounds logical, but if you investigate the situation, not a lot of Black people actually left their estates, particularly field workers. Those who left wanted to get away from that stigma and moved into the villages where there was still a lot of big real estate. Leaving was a symbolic move away from slavery.

Indian Arrival Day Celebrations (May 5, 1838), date of photo unknown

Thibert: In 2017, you were asked the following question by reporter Oscar Ramjeet, “Did Marxism fail because it could not bring the two main races together?”

Your response was “No! Marxism is still the most potent tool for analyzing society and actions in both international and domestic affairs. Those who say Marxism failed are people who are dogmatists…who do not understand that Marxism is a science. But look at how creatively the Chinese Communist Party has used Marxism to build China and to contribute to international development, despite recent setbacks internationally of Socialism. Look at how Vietnam is rapidly rebuilding, after decades of devastating wars using Marxism as their tool.”

I am curious to know if you still feel the same way. Did Marxism fail because it could not bring the two main races together?

Ramotar: I still feel the same way. Another point that I want to make to you is about one of the reasons the British and Americans changed the electoral system in our country from constitutional to PR. When Burnham decided to split the party in 1955, race was a big factor. It was being used openly by the PNC.

From that time on, I gained many of my life experiences as I was old enough to recognize a lot of those things. In 1962, I was 12 years old. So, I was aware about what was going on, as I grew up in Georgetown and went to school there at that time.

Despite all of the pressures the PPP put on the government by not allowing it to have money and carry out its programs, the PPP won at least three seats in the 1961 general election—the last election we had under the constitutional system. The majority of electoral votes were cast by Blacks, and the PPP won those seats. I think they decided to change the system in order to defeat us. That decision made the racial propaganda more potent in organizing the people under racism.

The same thing happened, though not necessarily with race, in Chile in 1970. When Salvador Allende won the president election, they (United States) put pressure on the government to make it fail, but when parliamentary elections were held in early 1973 and Allende increased his majority, the U.S. decided he had to go.

I am trying to say the constituency system, albeit not perfect, is in my mind a better system to help with race relations in the country.

Thibert: Is your current (electoral) system because of the British government or because the United States pushed it in the direction it went?

Ramotar: Yes, well, yes. The first person who mentioned this after the 1957 elections was the head of Bauxite (Company of Guyana), the biggest company in the country. He made a statement about the PR. No one took him seriously at first, but they did after the 1961 elections when the PPP won.

I don’t think Burnham necessarily believed in PR because he did not campaign for it, even in 1961. When he lost the election in 1961, he demanded PR before independence.

Thibert: Tell me about the Political Affairs Committee (PAC), former President Jagan’s initial foray into politics. What prompted the formation of this committee? What lessons did Jagan take away from his experiences?

Ramotar: My own view is that after he came back to the country in 1943, he started looking and getting involved in its politics. He worked with some trade unions, and he wrote papers. There were some programs with weekly discussions, and he went there and so on, but I believe the idea came to him about forming the PAC after he met Jocelyn Hubbard and Ashton Chase who were both Marxists.

According to Jagan’s wife, Janet, they met Hubbard and Chase while window shopping, and they passed a store and saw a book by Lenin—the first time they had seen anything like that. They went into the shop and met Hubbard and he introduced them to Ashton Chase, who was very young and working with the British Guyana Labor Union.

I don’t have any proof of this; this is only my speculation. I think they took the model of the Soviet Communist party that Lenin started with a newspaper called Iskra, and I think they took that model to educate people.

They (Jagans) used to print a newspaper and those newspapers were used as a basis for discussion groups all over the country.

By 1949, two of the groups made a resolution to turn the PAC into a political party. This was their objective from the very beginning because, when they formed the PAC, one of their objectives was to lift the consciousness of people, dissimilate news to them, and form a political party.

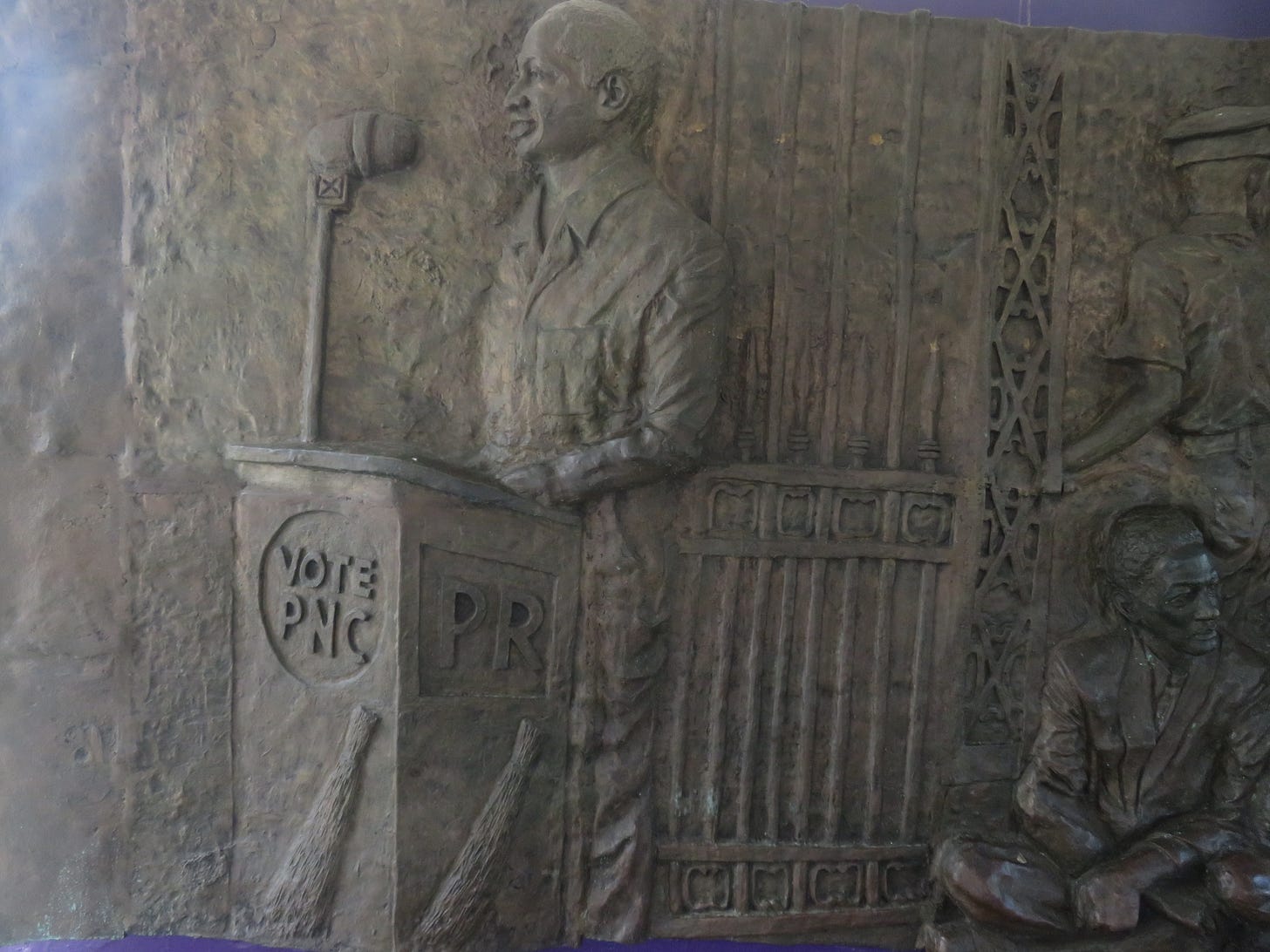

Depiction of Linden Forbes Burnham, Burnham Mausoleum, 2024

Thibert: In 1953, the PPP government was dismantled. The British, under duress from the U.S. suspended the current Constitution. During this time, fractures and disunity were happening within the party. Can you provide clarity on what was happening?

Ramotar: It was a shock. Cheddi (Jagan) wrote a book called Forbidden Freedom shortly after the suspension of the constitution. In that book, he expressed how surprised he was. There were not any uprisings in the country, riots, difficulties, or problems. Things were running normally.

Jagan was, however, hearing news that the British were planning to invade. He tried to raise this threat several times in the National Assembly, and the governor said, “No I’ve heard nothing of the kind.” Then on October 9, 1953, the British landed their troops to overthrow the government.

The invasion was a surprise, and then it was not a surprise because Jagan was getting information that the British were organizing some troops in Jamaica to overthrow the government. Everyone was denying it. In fact, the day when the troops landed, there was a big cricket match being played on the grounds in Guyana. That’s one of the reasons the population was shocked.

Thibert: Let’s fast-forward a bit. In 1961, former President Jagan had his now famous meeting with former U.S. President Kennedy. This meeting is now notable for the moment when Kennedy came to the conclusion that “Jagan was dangerous and unsuitable to lead the country.” How long did it take the rest of the PPP to realize Kennedy was not happy with Jagan?

Ramotar: I think it was at his same meeting with Jagan. Kennedy subsequently arranged for Jagan to meet with his economic team, and when he met with the team, Jagan realized that the team was only dragging him along. They did not intend to give him anything.

After the meeting, Jagan wanted to meet Kennedy again, but Kennedy gave instructions to his people where they should not break off the talks with Jagan, just keep him hanging on but don’t give him anything.

The British, in my view, had the experience of working with Jagan from 1957 to 1961 and saw how much work he was doing and how the country was transformed. Even though he had different resources, he was managing the country with an absence of corruption. The British had a change of heart, I believe in 1961 when they were saying that they should work with Jagan.

In contrast, the Americans were not willing to work with Jagan. I think it was not because of anything that was happening in Guyana. None of his policies was described as communist. In fact, a British officer said, “You’re mistaking Cheddi Jagan’s nationalism for communism.”

The Americans were not willing to take the chance largely because of what happened in Cuba. The Cuban government was becoming very influential in Latin America, and the American government was approaching elections. I don’t think Kennedy wanted to face the elections when he thought that a progressive government in Guyana could be used against him.

Prime Minister Cheddi Jagan meeting with U.S. President John Fitzgerald Kennedy at the White House, 1961

Thibert: Was former President Janet Jagan the real visionary behind the PPP?

Ramotar: No, no she’s not. Of course, she was a capable woman, but she was not a theoretical type. She was practical and organizational. Cheddi Jagan had both qualities. He was an activist and a deep, theoretical thinker. If you read his writings, you will see that he was head and shoulders above her intellectually.

Thibert: Can you elaborate a bit on the February 1962 Kaldor Budget riots that were supposedly due to Cheddi Jagan’s budget announcements, which were seen as insulting to Africans? Why were Jagan’s announcements so inflammatory? Can you shed some light on the incident?

Ramotar: I will say this was a clear case and a clear indication. I think 1962 was an important year. The Kaldor Budget was more pro working class then it was for business. The fact that we were going toward independence meant we had to prepare the country. The British and the Americans were starving the country of resources.

Jagan asked the United Nations for help in assigning a good economist. At that time, we didn’t have many qualified people in Guyana. The United Nations decided that to help Jagan a lot and sent Kaldor to help him my. Jagan wanted someone with tax experience. The taxes in the Kaldor Budget were more on luxury goods, such as motor cars, fancy watches, perfumes, and so forth. These taxes were not enough for Kaldor, and so some food items were taxed at a minimal level like imported potatoes and other basic foods.

These taxes were the pretext for the riots. Actually, there is something you should know. A trade union started the strike, supported by the PNC and the U.S. You should also know about the Trade Union Congress in 1953 when the constitution was suspended. Not only was the PPP government removed from power, the PNC was disbanded. Then the PNC was reassembled and three months later put in leadership that was sympathetic to the colonial powers. The new members of the PNC wanted to send a message to the British government congratulating them for removing the PPP from office. The PNC was encouraged to take a racial position opposed to non-racial position of the PPP.

The PNC started the strike. At that time, the Americans had trade unionists in the country from the CIA to guide their actions. All of the commentators who are supposed to be independent, neutral, and so forth, all said that it was the best budget and what was needed for a country going toward independence. So, I would say the position of the Kaldor Budget was a pretext and not the real reason for what happened.

Thibert: In the 1980s, Halim Majeed attempted to bring “reconciliation and organic unity” to the political parties. Discussions had begun, but due to Burnham’s death, they were halted. Are you familiar with this event? If so, can you provide clarity on why talks did not continue under (Former President Desmond) Hoyt?

Ramotar: I know him very well. Halim is, maybe, trying to make a name for himself in history because he had no authority. He was not even in the leadership of the PNC. He talked to me actually, at one time. He had a meeting with me and a friend of my mine who died by the name of Kolmar Chan, and he was speaking about the possibility of how we can get the people together so on and so forth. It never got beyond that conversation. He wrote a book and tried to make it look like he was doing a lot. He had no leverage, let me put it that way.

Thibert: A few Afro-Guyanese have said to me “Black Guyanese vote for PNC. Indo-Guyanese for PPP. They’d all rather vote for no one than cross the color line.” In your experience is there any truth to this?

Ramotar: There is some element of truth in this. Because, in fact, my argument to deal with that is on the ground in the amount of work this government (PPP) has been doing from 1992 to now. In all the areas, the Afro-Guyanese have benefited just as much as any other group in the country.

Although the PNC still talks about racial discrimination, there really are no grounds for any of this talk. If the situation was as bad as they said, then we could not maintain a government for a day or week because the whole army is about 90% Afro-Guyanese and the police force is about 75% Afro-Guyanese.

I think most of it is emotional attachment. It is true that sometimes it transfers to the way people vote. Instead of voting their interests, they tend to vote race. So, I would say there is an element to truth in that. Even so, we are seeing changes in that as well. In the last local government elections, the People’s Progressive Party/Civic (PPP/C) got increased votes in several areas where we didn’t have voters before, and even in other areas we won the position of mayorship in Mahdia and Bartica. So, I would say that there is a large amount of truth about racial-based voting, but we are seeing some real changes.

Former U.S. President Jimmy Carter meeting with President Desmond Hoyte, 1992

Thibert: Tell me about The Herdmaston Accord. Why did former President Janet Jagan agree to reduce her term?

Ramotar: Ok. I think she was very emotional because of the riots the PNC started in town. In fact, she said so herself at a meeting of the Central Committee of the PPP. There was some criticism about her signing the Accord saying that “Why should we do that? If we agree to have the votes recounted and we won the election, why should we make that type of concession?”

She then said, “I lived through the 1960s and I would never want to see something like that happen again to the country.” I think it was playing on her mind a lot. She was now the number one person in the party. I don’t think she wanted to see another riot that could have possibly ended up as racial riots. It was not a rational decision; it was an emotional decision.

Thibert: Let’s jump forward a bit to your presidency.

You stepped into the presidency at a very polarizing time. Some of the major issues affecting the country (Guyana) were widespread crime and poverty, fear of the police, corruption, and racism in politics. Were you able to make any headway in alleviating any of this during your term?

Ramotar: No, but I think what you said is a little bit of an exaggeration. I would say that in the three and a half years that I was president, the country did not regress, despite the difficult condition of having an active opposition with a majority in Parliament.

The economy still grew an average or 5% a year over my term. There was no mass employment, no increase in unemployment, and no decrease in the supply of food. It was just the opposition making it difficult to govern and implement our many transformative projects.

They voted against, for example, the capital budget and, in many cases, we had to go through the courts to restore it. They slowed things down, such as the hydroelectric falls project that would have given us 165 megawatts of electricity and renewable resources from the falls. I gave them all the studies to show it was a viable project, but they still voted against it. The public excuse that they made was that the project created a big debt for the country. This was a total lie because it was an arrangement with a company from a U.S. company owned by Blackstone.

We had an arrangement that they would build the plant and operate it for 25 years. Then it would revert to the government, but they voted against it. Going toward the election, Blackstone walked away from the project. That’s why the project never got done.

The other case was an anti-money-laundering bill pushed by the United Nations. That bill, I think, wanted most of the country to have similar types of financial arrangements to try and prevent money laundering and drug smuggling.

Before the PNC got the majority in Parliament from the beginning of 2000, we used to vote for the bill automatically every year. But the moment they got the one-seat majority, they started to vote with all their support in the hope that we would get blacklisted. That would have cut into the heart of our economy and the financial sector. They did not actually do that. They recognized that we did everything that was possible administratively.

Thibert: In 2014, Kaieteur News published the article, “Ramotar’s presidency has brought nothing but continued corruption.” It states that the observations of ordinary Guyanese were that the status quo was kept during your term.

Ramotar: This is not true what you have described under my presidency. I mean to be very objective because like I said the economy kept growing. We were on the verge of having universal secondary education when I left government and it fell back. Now we are going back in that direction again. My presidency feels small compared to what we have now because of the oil. We started from a low base and we jumped forward.

If you compare Guyana to the rest of the CARICOM, I think it’s comparable to what was taking place in the rest of the region.

Thibert: In 2015, former President David Granger stated, “The time has come for racial and national unity.” In 2016, you backed former President Jagdeo’s statement about racism toward Indo-Guyanese. Specifically in regard to a number of rural nationals being hit with new taxes and an apparent 90% of Indo and Amerindians losing their positions or vacating them, how did former President Granger bring unity?

Ramotar: I don’t think he brought unity. That’s why he lost the election. From the very beginning, they started to dismiss a lot of Indo-Guyanese from various positions in government from top policy positions where they might want to have their own party people. This spread down to people like cleaners, gardeners, and so on.

I think Jagdeo was right about how they were practicing heavy racism in the country. It probably satisfied some of their voters because they were pushing a strong Black line. They had to try and give them some jobs to keep them quiet. They did it at the expensive of Indian people who wanted very small jobs. They put on a lot of taxes—200 more taxes on different items. In that case, everyone got hit, not only Indians. Even when PPP was in government under Jagdeo, they reduced the value added tax (VAT). What we did was exempt any essential food items, including medicines, educational books, computers, laptops, and so on. They were zero rated.

They (PNC/R) were campaigning against this when we reduced it. They said that if they get into government that they would cut it to 8%. We had it at 16%. They never did anything when they got into government. They kept the 16% tax for a few years, then they cut it by 2% to 14%, but by then what they did also was to tax everything, food items and educational stuff and removed the zero rated. They collected even more money with 14% than we collected with 16%.

Thibert: During your term, you pardoned Donald Rodney and helped facilitate the requests from his family to correct his legacy. Why? There is no doubt you knew how the PNC would respond to this action.

Ramotar: When the Commission of Inquiry on the Death of Walter Rodney began, Donald Rodney (Walter’s brother) was living in Trinidad. I understood that after what happened with Walter in his absence, Donald was convicted and never wanted to come back because he was afraid the police would arrest him. He wanted me to knock out the case completely and say it was a whole jiggery crockery and that Donald was set up. I was willing to do this, but then I consulted with the Attorney General, who told me that I could not do it. What was accessible to me was a Presidential pardon that would allow him to come home and give evidence and so forth.

He was not very happy with that. I gave him the pardon anyway and he did come home. After he came home, he went to the court and had the whole thing stricken. The PNC really did not want to be bothered with this because it may come back around to them.

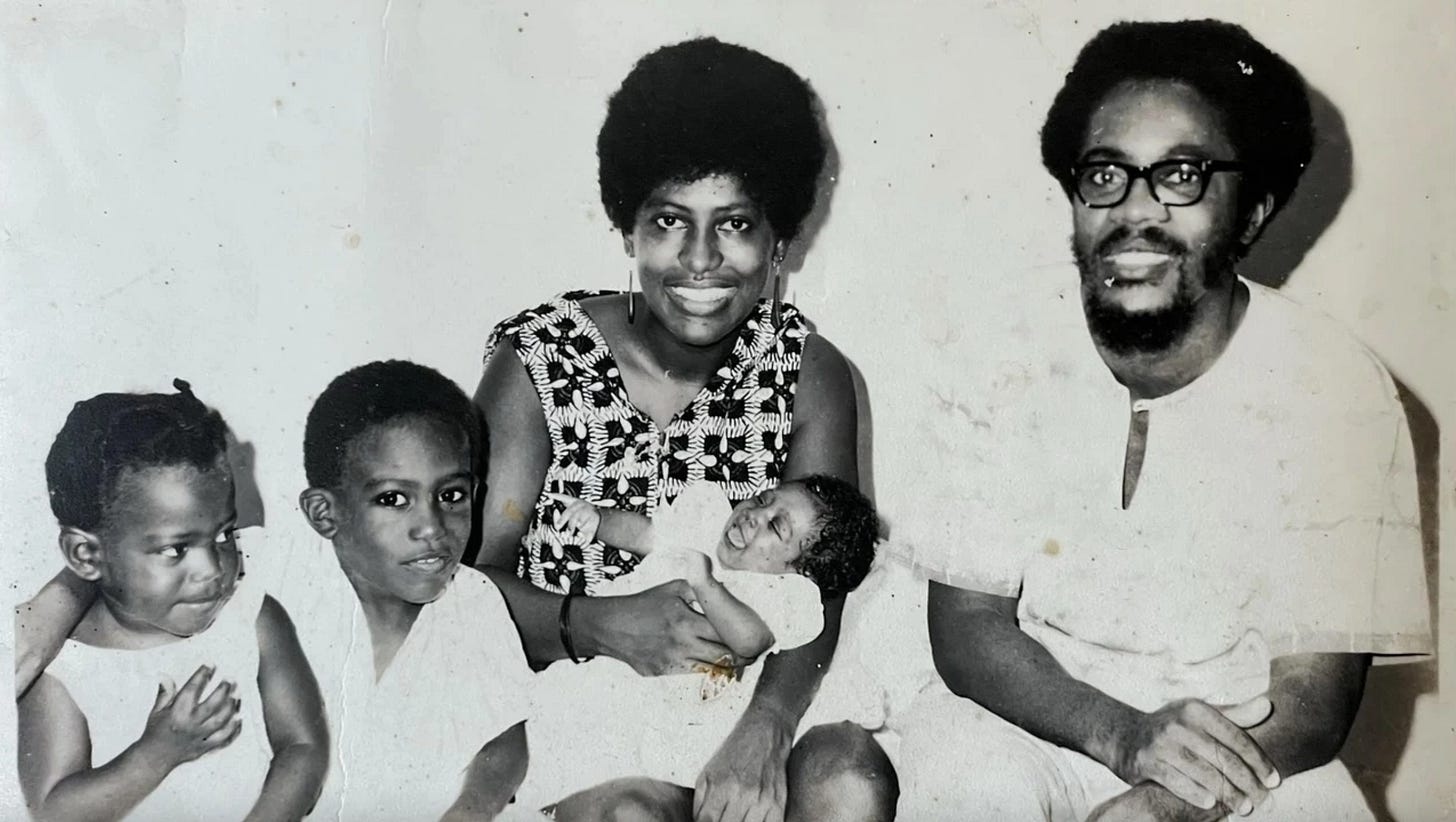

Walter Rodney and his family, date unknown

Thibert: Why did long-time PPP member Moses Nagamootoo switch parties in 2011? Can you tell me your thoughts in this?

Ramotar: I think he had a lot of personal issues with Jagdeo. There were a lot problems with him and Jagdeo within the party and he felt that Jagdeo was keeping him down. Therefore, there was a lot of bitterness between them.

Thibert: The Exxon oil discovery was made during the 2015 election. How did this discovery change relations between the two major parties? During your term, did you know that this discovery was going to be made?

Ramotar: It is difficult to know. Let me put it this way. When coming close to the end of my term, I had meetings with them. I think they had already found out, but since we were so close to the elections, they were not revealing it. They told me that they have very good indications of oil out there. Immediately after the election, they announced that they found oil. I would say it was in that twilight period that they found it. They probably found it under me but didn’t tell me.

Thibert: What were your thoughts of the end of Granger’s term?

Ramotar: Well, I thought Granger squandered an opportunity he had. His style of presidency was bad. He was very much aloof from what was taking place. I think he gave everything to his ministers to do. Do you know his background?

Thibert: He came from the military.

Ramotar: Like the military. He tried to run the government by just passing orders without trying to see if things were getting done. I think they could have made things better. Instead, they made things worse in the country. From the very beginning, they were planning to rig elections and stay in government forever. The first thing they did was to give themselves a 50% increase in salary and wages. Some of the measures they took indicated to me they were planning that they would steal the election, which they tried to do and they got caught.

Thibert: A lot of former President Granger’s self-published books have a theme of security and public policy. Did he run under a “law and order” platform to bringing safety and security to the country?

Ramotar: That is part of what they ran on. In fact, I thought, if you look at a purely racial point of view, they had this domination of African-Guyanese in the security police officers. I thought that might make a big impact and probably get more cooperation. The situation as far as crime that he was concerned about did not improve under their government.

President Ramotar meeting with then President Elect Granger, 2015

Thibert: Any regrets from your term as president? Which issues would you have continued to pursue if re-elected?

Ramotar: Well, a lot of regrets. I would have liked to stayed in government. My own personal view is that in the 2011 elections, there was some rigging against us that we didn’t pick up. We became a little complacent. In 2015 again, we thought there was the same rigging that they tried and got caught for doing in 2020. I think they succeeded at a lesser level in 2015. That caused me to come out of government. That is one of my regrets. We were not alert enough to prevent this.

I also regret that we did not have the chance to build the hydropower station. It would have brought a lot of prospects to Guyana as far as power was concerned. Some of those types of projects we definitely could have done. On the very last day, it was still legally possible to do them.

I always expected they would vote against the budget ending in a no-confidence vote. The result would be that we had to go through elections. I had to bring the budget in quite late. So, I think that we could have done more under normal circumstances, or if they had indicated any cooperation. Like I said in my speech at the opening of Parliament, it is not the worst thing that could happen. That would have helped us work together and cooperate. They never made any attempt. Instead, they used their one-seat majority not in the interest of the Guyanese people but to try and grab power for themselves.

Thibert: Are you still involved in politics? If so, what is your current role?

Ramotar: Well, I am not as involved as I used to be, but anything my party asks of me, I am willing to do. I still write for the press, but I am more involved in international tragedies like what is happening in Gaza. Our government seems very sensitive to saying anything against the U.S. I am practically the only voice saying anything against this war. I think it is important to raise your voice.

Thibert: Did former presidents Cheddi and Janet Jagan’s dream for Guyana survive?

Ramotar: I would say some of it did. Some of it is happening, but I think they probably would have been disappointed at some stuff. It seems to me that the influence from outside is becoming much, much stronger. Sovereignty for them was very important. Maybe this is my assessment. I think the outside influence is becoming stronger on us.

Thibert: Outside, as far as media? Government?

Ramotar: I think government. I think the United States has an even stronger influence here with oil. That is why, I believe, our government hardly says anything about them. I mostly say that at the level of the United Nations, they have taken a very positive position in some of these issues like the Gaza situation. Generally, you hardly hear our government say anything.

The question that I think we are afraid of and that still hangs on our shoulders is the experience of the 1960s and the fear that outsiders will interfere with us and send us back to a more undemocratic situation. I think that fear is an influencing factor.

Click below for an overview of the political history of Guyana:

Politics, Pigments, Oil (Guyana)

1992 Siege of the Elections Commission headquarters in Georgetown by a violent and angry crowd claiming they were not allowed to vote. (Credit: Carter Center)

Click below for an overview of the economic history of Guyana:

Whoah! Interviewing a former president. nice.

Hello, Guyanese here. The writer you reference here is actually Freddie *Kissoon*.