Policemen examine victim of the race riots in Chicago, Illinois, 1919. Credit: Jun Fujita/Chicago History Museum

On Saturday July 20, the Chicago Race Riot of 1919 Commemoration Project (CRR19) hosted the free 6th Annual Bike and Trolley Tour in remembrance of the biggest race riot in Chicago and the United States.

This event is funded by individual donors and grants from the Illinois Humanities; Niantic, Inc.; the City of Chicago via the Chicago Monuments Project, the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, and the Chicago Department of Cultural Affairs and Special Events.

This event also collaborates with the Firebird Community Arts’ Project Fire, the grassroots social justice organization Organic Oneness, the Chicago Center for Youth Violence Prevention (CCYVP), and the Greater Bronzeville Community Action Council (GBCAC)

According to Co-Directors Franklin N. Cosey-Gay of the Violence Recovery Program and Peter Cole, Professor of History at Western Illinois University, the tour’s existence is important, because the riot has been “long forgotten despite its impact on the subsequent shape and development of the city.”

Unfortunately, the mistakes that started the riot have been replicated throughout the 20th century and into the 21st in Chicago and in many cities with large communities of disenfranchised Black Americans.

African American veterans defended their communities from attacks by whites, while the state militia was called in to quell violence. Chicago 1919 Credit: Chicago Tribune Historical Dept

Segregated Zones

Eugene Williams was only 17 when he died on July 27, 1919. He and his friends John Turner Harris, Charles and Lawrence Williams (brothers), and Paul Williams (unrelated) unknowingly crossed the invisible race boundary that existed in northern states. One of those boundaries existed along the beaches of Lake Michigan—29th Street beach for Whites and 26th Street for Blacks.

Gray areas and gray rules existed between these segregated zones. One of those gray areas was a small island, between both beaches, that the boys designated as their clubhouse. To get there, they used a raft of their making to escape the humid summer air that mixed with the waste of the neighboring Keeley Brewery and Consumers Ice Company.

A small group of white men began heckling those boys. Upset over the perceived transgression of swimming in their waters. The group included George Stauber who threw a stone that struck Eugene Williams rendering him unconscious as he swam in Lake Michigan. His crime? Unknowingly swimming into a Whites Only area.

Justice could have quelled the matter, but Officer Daniel Callahan’s refusal to arrest Stauber turned into a protest. That protest turned into widespread anger as more police arrived. When officers became aggressive, a Black protestor named James Crawford fired his pistol and the police fired back and killed him.

To give what happened next some context for the racial dynamics in 1919, the South Side neighborhoods of the Black Belt (today Bronzeville), the nearby ethnic neighborhoods of Back of the Yards (today New City), and the Bridgeport areas were where the working-class populations lived. A large majority of those in the Black Belt community were from the South.

Black Americans who ventured North as part of the Great Migration from a variety of states below the Mason Dixon lived in cramped tenement quarters with low wages and poor conditions. Their employment was in neighborhoods accessible only by public transportation on the North and West Ends. There, they served as domestics or in buildings and restaurants within the Loop (Downtown) as waiters and house keepers. Over time, a few people gained employment at one of the meat-packing plants as union men. But higher paid jobs at this time were far and few between.

Alongside them were enclaves such as Packingtown, which co-existed within the Black Belt. The people who live there were Lithuanians, Poles, Irish, and Germans. Most of them worked at the Union Stock Yards, slaughtering animals and working various roles within the slaughterhouses .

“The world of Packingtown was tough and poor, a collection of shanties and shops in the shadow of the Yard. The chimneys of Swift’s packing plant stood tall against the sky, belching thick smoke that spread over Packingtown like a blanket, smothering the community below in the stench of blood” From A Few Red Drops: The Chicago Race Riots of 1919 by Claire Hartfield (2018).

Similar to the Packingtown enclaves where both Back of the Yards and Bridgeport neighborhoods were, Eastern European immigrants also lived in cheap workingmen’s cottages in the shadows of the various plants they lived between.

Low pay, poor living conditions, humid weather, and a summer already filled with multiple racial incidents, in other parts of Illinois, was the powerful combination that took only one more event to ignite a city full of anger and frustration.

Historic Marker for Hymes Taylor. One of the victims of the 1919 Race Riot. Credit: Mike Slattery

Taking a break. Chicago Race Riot of 1919 Commemoration Project 2023 Bike Tour Credit: CRR19

CRR19

In 2009, a plaque was paid for and installed by Chicago area high school students at the 29th Street beach where Williams died and the riot began. In 2019, the City of Chicago, under Mayor Lori Lightfoot, officially recognized the event. But after the Chicago Newberry Library asked, “Why are Chicago’s race riots of 1919 overlooked in the city’s collective memory?”

After the official launch of the public history and art project known as the Chicago Race Riot of 1919 Commemoration Project (CRR19) on July 27, 2019, the first bike tour was held in 2020. Since then the organization has established relationships with various groups to keep the event relevant, educate the community and make the riot relevant to individuals and communities.

In 2020, The Eugene Williams Scholarship Fund (EWS) was launched with the support, collaboration, and endorsement of the Greater Bronzeville Community Action Council (GBCAC) Surprisingly, it began with a donation from a descendant of Frank Ragen, a gang member who participated in the riots. His donation was turned into a fund to provide aid to two graduating youths between the 8th and 12th grades from the community on the anniversary of the riots.

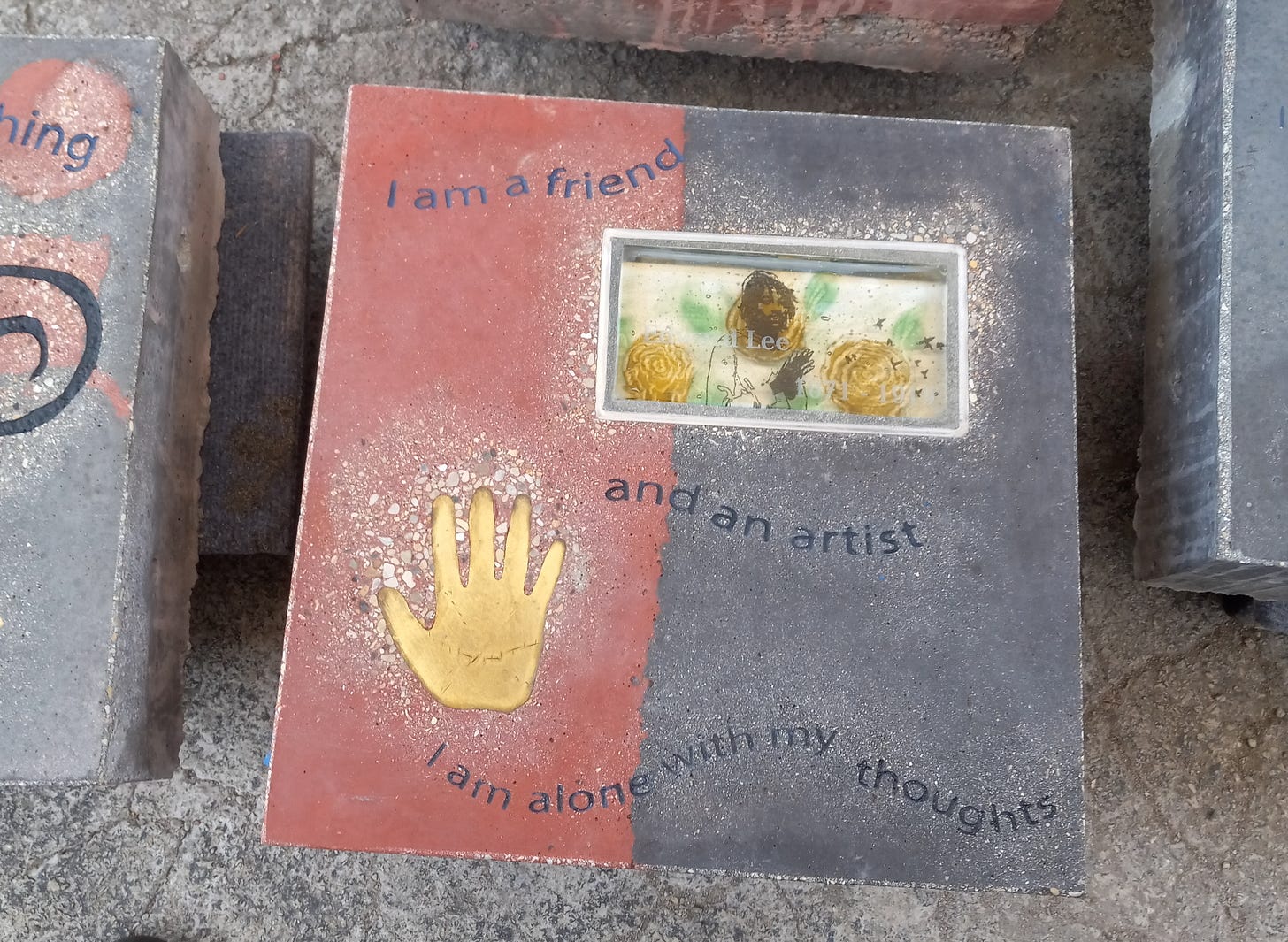

Project FIRE of the Firebird Community Arts developed 38 durable glass blown structures to be installed throughout the city as a gift to the City of Chicago. Their purpose: to bring to the foreground stories of undocumented, immigrant, underage, formerly incarcerated, veterans, and students who have been impacted by structural or interpersonal trauma.

One of the 38 glass blown structures donated by Firebird Community Art’s Project Fire to the City of Chicago. Credit: Mike Slattery

The Chicago Center for Youth Violence Prevention (CCYVP), Greater Bronzeville Community Action Council (GBCAC), and Bright Star Community Outreach (BSCO) are all working at the community level to better understand, diagnose, and treat the effects of violence and offer opportunities and pathways for anyone affected by it or looking for resources to assist in education and quell past or potential trauma on the South Side.

In addition, CRR19 offers in-person presentations (and virtual) at Chicago Public Schools. The Facing History and Ourselves initiative has made the teaching of the Red Summer of 1919 a part of the local history curriculum as the first step to understanding what happened on July 27th and hopefully avoiding a repeat of history.

Some of the people behind CRR19. Co-Directors Franklin Cosey-Gay (L). Peter Cole (olive green shirt) Credit: CRR2019

Gangs of Chicago

According to the 12-person, mixed-race Chicago Commission on Race Relations (1922) organized to find the causes of the week-long riot that resulted in 38 deaths (23 Blacks and 15 Whites) led by the research of Black sociologist Charles S. Johnson and approved by Mayor William “Big Bill” Hale Thompson.

“Gangs and their activities were an important factor throughout the riot. But for them, it is doubtful if the riot would have gone beyond the first clash. Both organized gangs and those which sprang into existence because of the opportunity afforded seized upon the excuse of the first conflict to engage in lawless acts .” taken from the Negro In Chicago 1922

The Stock Yards area was a breeding ground for most of the White gangs and “athletic clubs” who found opportunities to punish Black residents throughout the city. Some of these groups went by names such as the Canaryville Club and Hamburgers Club, Lotus Club, Mayflower Club, Ragen’s Colts, The Lorraine Club, Our Flag Club, Sparkler’s Club, Alyward Club, and Rainer Club.

“There was much evidence and talk of the political ‘pull’ and even leadership of these gangs with reference to their activities in the riot. A member of ‘Ragen’s Colts’ just after the riot passed the word that the ‘coppers’ from downtown were looking for club members, but that ‘there need be no fear of the coppers from the station at the Yards for they were all fixed and told to lay off on club members.’ During the riot, he claimed they were well protected by always having a ‘cop’ ride in one of the automobiles so everything would be ok .” Statement taken from the 1922 Riot Commission

Throughout the riot, Black Chicagoans were targeted on their way to or coming from work. In some cases, they were targeted at work. Homes were bombed and businesses were raided and destroyed. Families were forced to flee their homes as police often stood by and, in some cases, arrested Black Chicagoans attempting to flee the carnage.

In one instance, John Mills was pulled from a street car and murdered. A police officer later attested that the crowd was not an aggressive mob. In another instance, Francis Green was attacked by 30 White men who shot him on the corner of Garfield Boulevard and State Street outside their “hangout.” He was only 18.

As soon as the news got out that the boy, Williams, drowned, the State’s Attorney Thomas Maclay Hoyne declared that it was the “colored gamblers who started this shooting and tearing around town.”

It was later learned that organized bands of White youths were burning Negro dwellings and taking anything of value. Black Belt clubs were raided, and shut down.

“In the opinion of this jury many of the crimes committed in the ‘Black Belt’ by whites and the fires that were started back of the Yards, which however, were credited to the Negros, were more than likely the work of the gangs operating on the Southwest Side under the guise of these clubs, and the jury believes that these fires were started for the purpose of inciting race feeling by blaming some of the blacks. These gangs have apparently taken an active part in the race riots, and no arrests of their members have been made as far as this jury is aware .” Statement taken from The Negro in Chicago, 1922

By the fourth day, the state militia was called in, but the fighting continued until August 3. Over 500 people were injured, the majority of whom were Black. Justice was never adequately delivered. Employers shuttered their doors, and those that stayed open barred Black workers. Property damage and lack of work left many families impoverished and in worse living conditions than before the riot. The various white clubs involved were protected, while Black residents served jail time.

In conclusion, eight causes were determined to be the true source of the riots: race prejudice, economic competition, political corruption/exploitation of Negro voters, police inefficiency, newspaper lies about Negro crime, unpunished crimes against Negros, housing, and reaction of Whites and Negros from war.

The end result left deeper divisions between Black and White communities that festered and became worse with the creation of stricter policing of Black Chicagoans.

Main story. The Chicago Defender. August 2nd 1919

Vortex of Violence

When riots take place, the people who are lost become reduced to statistics. More often than not, one person (like Eugene Williams) becomes the face of the event , while others are simply forgotten. During the bike tour (July 20 at 10 a.m.), the 38 individuals who died were invoked to remind everyone of the people who, in some cases, were trying to avoid the violence around them.

Joseph Sanford (died July 28, 1919) was one of five men murdered during the Angelus Riot at the all-White Angelus residential apartment building. He left behind his wife Mary Williams. A claim had spread that a Black child was murdered, and a Black mob and the police both arrived at the building. Conflicting reports stated that either a brick was thrown or shots rang out, causing the deaths of five men—four Blacks and one White.

At the former Back of the Yards neighborhood, nine lives were lost. Among them was Joseph Powers (died July 29, 1919) a street car conductor who was stabbed to death when he and a friend confronted a Black group.

In the Black Belt (Bronzeville) neighborhood, many lives were claimed, including Theodore Copling (died July 30, 1919) who was an innocent bystander. Samuel Banks (died July 30, 1919) was shot and killed by police while trying to leave the area, which made him guilty on suspicion. Eugene Temple (died July 28,1919) was a white man who was “attacked by three Negros, robbed, and stabbed” after completing his laundry and leaving the laundromat with his wife Grace.

People also died at the Loop (Downtown). Robert Williams (died July 29, 1919) was a Black janitor stabbed by a White mob. In a rare case of justice, Williams’ murderer, 17-year-old Frank Bigart (a.k.a., Biga) was given a life sentence at the Joliet Penitentiary.

Turning back to the body count, Harold Brignadello (died July 28 1919) when he joined a White mob attacking a Black-owned home and was subsequently shot when the residents fired at the crowd to repel them.

Just as important today are the places along the bike route that were important to the Black Chicago community and city as whole and that were flashpoints during the riot.

The original Chicago Defender Newspaper (1905) Building, founded by Robert S. Abbott, served as the lifeline and voice that attracted transplants from the South to Chicago. It was one of the few places that Black Chicagoans could get news that affected them. The intersection of 35th and State was dubbed the “Vortex of Violence” as it was the epicenter of violence during the riot. The Union Stock Yard Gate was the portal to the former meatpacking plant that employed many immigrants and where Black workers were often used as strikers. Armour Square Park served as the unofficial dividing line between the Black Belt neighborhood and the White Bridgeport neighborhood.

Over time, a goal of the CRR19 is to install commemorative markers on all 24 sites related to the riot. As of today, 14 have been installed to help remind passersby of this part of local history. But is it enough?

Director Franklin N. Cosey-Gay discussing a landmark during the 2023 Bike Tour. Credit: CRR19

Commissions and Reports

Local and federal governments have known for some time how to stop riots before they happen. The already mentioned Chicago Commission (1922) gave definitive answers as to the cause of the Chicago riot and provided a road map. The information gained was subsequently ignored. Economist Gunnar Myrdal’s study, An American Dilemma: The Negro Problem and Modern Democracy (1944), plainly stated, “the solution to the problems of American discrimination lie in white society’s free will to embrace all citizens equally.”

In 1965, a congressional mandate approved a study on the equality of opportunity in racially segregated schools. Released in 1966, and dubbed The Coleman Report after lead sociologist James S. Coleman, the Equality of Education Opportunity (EEOS) report “assessed the availability of equal education opportunities to children of different race, color, religion, and national origin.” The controversial report moved to desegregate schools based on the findings that “a pupil’s achievement is strongly related to the educational backgrounds and aspirations of other students in school.”

Simply put, scholastic competition can drive students to do better and be better. The results assisted in desegregating schools. An action later rescinded due to white parents protesting against bussing kids and mixing races. American schools are still suffering due to inequality and inaccessibility to education.

After a total of 150 race-related riots throughout the United States in 1967, perhaps one of the most widely known commissions on finding answers to the racial issues behind many riots was commissioned by then President Lyndon B. Johnson (July 28, 1967.)

“The only genuine, long-range solution for what has happened lies in an attack—mounted at every level—upon the conditions that breed despair and violence. All of us know what those conditions are: ignorance, discrimination, slums, poverty, disease, not enough jobs. We should attack these conditions—not because we are frightened by conflict, but because we are fired by conscience. We should attack them because there is simply no other way to achieve a decent and orderly society in America.” Lyndon B. Johnson

The Kerner Commission released its findings on the root causes of inequalities in then recent riots in Tampa, Cincinnati, Atlanta, Newark, New Jersey, and Detroit. The report included conclusions such as “Often it is assumed that there was no effort within the Negro community to reduce violence. Sometimes the only remedy prescribed is application of the largest possible police or control force, as early as possible” (Kerner Report pg. 37) and “Social and economic conditions in the riot cities constituted a clear pattern of severe disadvantage for Negros as compared with whites, whether the Negros lived in the disturbance area or outside of it” (Kerner Report pg. 77); To me, one of the most impactful statements, “The most common reaction was characterized by the last of the quoted expressions ‘nothing much changed’ and the status order was quickly restored after the riot.”

Lastly, both the Watts Riots (1965), Rodney King Beating (1991), and Los Angeles Riots (1992) resulted in three separate commissions; McCone Commission Report on Watts Riots (1965), Christopher Commission (1991), and Webster Commissions (1992). Each commission came to similar findings that were already uncovered in other reports. So, the question becomes “why aren’t we listening to the results?”

Reel America Preview: "Remedy for Riot" (1968)

Conclusion

From time to time, talks of a potential race war or how dangerous urban neighborhoods are make the press circuit. Each scenario gets played up to an almost fantastic degree, which often makes suburbanites scared of anything related to designated “ghetto” areas. Yet we have information about what causes those areas to not only remain but also remain dangerous to both residents and the city at large. Solutions are often ignored in favor of short-term band-aids such as increased police presence.

We know that education improves quality of life. We know that after-school programs and summer activities get kids off the streets. We know that encouragement fosters pride. We know that improved neighborhoods and opportunities do the same.

We only have to look at the George Floyd Riots (2020) to see that we still have an issue that stems not just from the death of George Floyd but from unanswered problems within underserved communities.

On July 20, 2024, the Chicago Race Riot of 1919 Commemoration Project (CRR19) highlighted a pivotal piece of United States history. Not only because the riots was an event that should be remembered but because it is an event that might happen again.

To make a donation to the CRR19 Project please click here.